A question I often ask, as I talk to meetings and groups, is “which of the following is the commonest cause of premature death in your area?”

- Cancer

- Cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke).

- Liver disease

- Lung disease

What do you think? Of course you could dive straight into Longer Lives and find the answer, but without this information, many people would say “cardiovascular disease”.

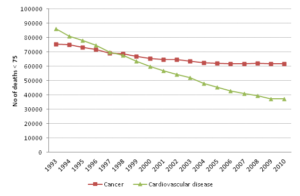

In fact, cancer deaths in people aged under 75 have outstripped cardiovascular deaths in England since the mid-1990s.

Source: Compendium of population health indicators; https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/webview

This is not to downplay the importance of any of these causes - cancer and cardiovascular disease account for two thirds of all premature deaths. Of the “top five” they have one thing in common – they are largely preventable.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates about two thirds of all premature deaths are avoidable – that is, they could potentially be avoided by public health action (preventable), better health care (amenable) or both - and that preventable deaths make up about half of all avoidable deaths. The opportunity is great for PHE and the new public health system to contribute to a reduction in the underlying causes and risks of poor health – smoking, excess alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and rising levels of obesity.

So, how are we going to do it? Working with our local government and NHS partners, we will play our full part in the “Call to Action” to reduce premature mortality. England remains “mid-table” in terms of European premature mortality rankings and we are determined to do better. Putting into action the things we know work and ensuring we do things at scale could save thousands of lives. Work is under way to allow us to better understand the full potential impact of public health interventions.

One important tool which will help us in this endeavour is the Global Burden of Disease study, which was published for the UK in March this year. Work is ongoing to produce this at sub-national levels. It reminds us that there are other conditions such as mental illness and musculoskeletal disease which contribute greatly to the overall burden of disability in the population, as well as the importance of high blood pressure as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. There is good evidence that increased levels of physical activity can improve all three.

PHE is committed to basing policy and practice on evidence, and that means making sure that both the public and local decision makers have, and understand, the best available evidence. Although data doesn't change things by itself, clearly presented information can be viewed as an intervention in its own right.

Finally, we need to recognise that the causes of ill health are constantly changing over time. While there is more awareness of the increase in liver disease, we should also recognise that other significant causes of preventable death have grown over the last ten years; namely malignant melanoma and accidental injury. PHE is committed to ensuring we have the right information in the right place at the right time.

How else do you think information could be used - by PHE, local government or others - to contribute to reducing preventable deaths? What sorts of data tools could we create to help us harness that information?

6 comments

Comment by Jo posted on

You might enjoy this http://theoccasionalpigeon.blogspot.co.uk/2013/09/new-government-plan-to-beat-obesity.html

Comment by John Newton posted on

Thank you Jo. The pigeon reports a wonderful idea but perhaps it needs further development!

Comment by Paul Jarvis posted on

Low cardio respiratory fitness is the cause of 17% of all early deaths (smoking 9%, obesity 2%). Improving fitness saves lives. We need to obsess less about weight. See http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/childhood-obesity-obsession-masks-fitness-time-bomb-8846597.html

What would really help to drive up investment in life-saving and cost-effective physical activity interventions is an agreed system of standardised measurement. At the moment, there is no standardisation so commissioners don't know what to ask for and providers don't know what to aim for.

Comment by John Newton posted on

Paul, you make a really good point that the role of physical activity does not always get the emphasis it needs partly because it is so difficult to measure realiably. What else can we do to raise the importance of physical activity and to add some rigour to commissioning of relevant interventions?

Comment by nick cavill posted on

Hello John. I enjoyed reading this blog. While I agree that it is important that any interventions that are commissioned are based on evidence of effectiveness, I worry that this means we will tend towards commissioning the same old tired small scale piecemeal schemes. For me what is exciting about the current arrangements in public health is that the traditional barriers between public health and transport (and perhaps less crucially, sport, leisure and cultural services) are being broken down. This opens the door for public health people to increase their influence on the policies that matter, especially local transport policy. I look forward to hearing more examples of partnerships between health and transport that are genuinely trying to prioritise walking and cycling as modes of transport in their towns and cities.

You asked about information: I think more than ever we need examples of innovative examples of practice that are well evaluated. We are working on some PHE briefings on fast food and physical activity that I hope will help to fill this gap.

Nick Cavill. PHE obesity knowledge and intelligence team

Comment by zbigniew lesiak posted on

To gather a huge ammount of information about the effectiveness of cancer treatments every new patient could be given the chance to update a simple website from their own home or local ibrary or internet cafe. Their input could include data on complimentay therapies which would otherwise not be tracked. Lifestyle, diet, location etc. could also be included to see how these effect their outcome and quality of life. This would be very cheap to set up as patients use their own computers and their own labour to enter the data. Patients may also get a satisfying feeling of "fighting back" and would be aware that they are the ones who would benefit from better data so they would be careful in entering the information. Even a small web server would suffice to handle the expected ammount of traffic if the data was simple enough and the data may prove invaluable for assessing treatments. Even results showing those treatments that have little or no useful effect would be helpful to people trying to decide on who and what to trust.