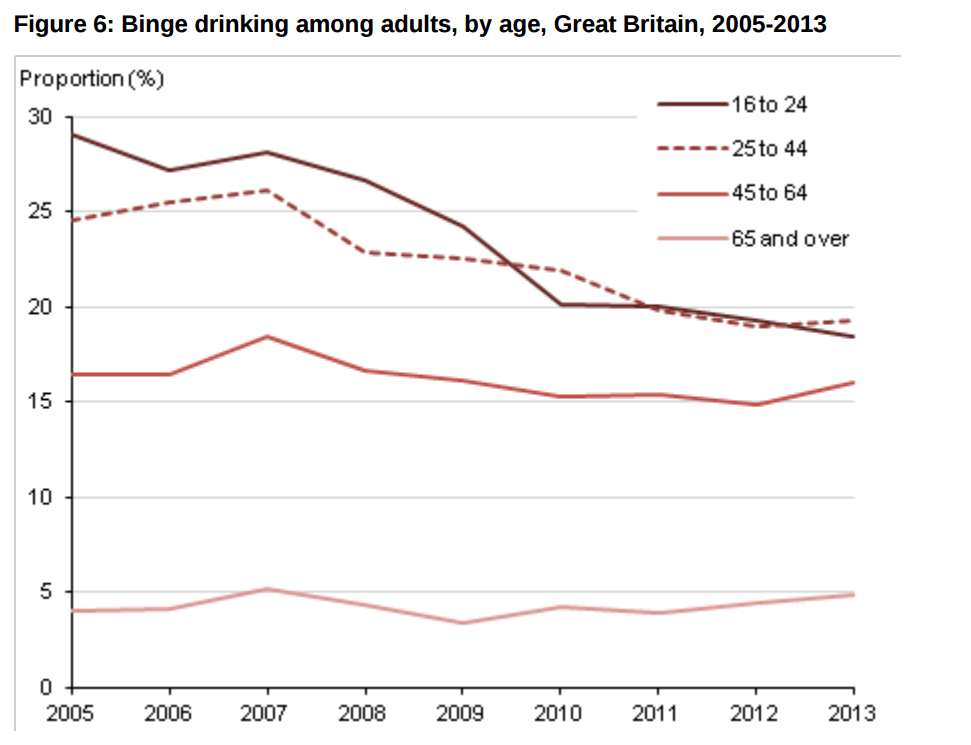

Recent drinking trends, across the population and among young people in particular, have shown that we are drinking less frequently compared with a decade ago.

In fact, young adults (aged 16-24) are now as likely to be teetotal as adults over 65, after a jump in the proportion of young people who say they don’t drink alcohol at all.

Binge-drinking since 2005 is also down dramatically among young adults.

There are other encouraging signs. The death rate from alcohol-related causes is the lowest it’s been since 2000. Among the under-18s, there’s been a continuing decline in hospital admissions related to alcohol, with a 41% decrease over the last 5 years. There’s also been a fall in alcohol-related violence over the past decade, consistent with a fall in overall violent crime.

But there are still significant sections of the population whose alcohol use is causing enormous harm. We need to be careful about interpreting average population figures as all good.

If reduced consumption is largely among health conscious people, who were not drinking much, then those who were already drinking at harmful levels will continue to be at risk.

And the damage isn’t distributed equally. For instance, the most deprived fifth of the population suffers two to three times greater loss of life attributable to alcohol, compared with the least deprived.

Why we can’t be complacent

Here’s why we can’t be complacent, and why reducing harmful drinking is one of Public Health England’s seven priorities:

First, the scale of the alcohol problem remains huge – whether we look at consumption, health impact or wider social harms.

In England, over 9 million people, or 22% of the population (nearly 1 in 3 men but fewer than 1 in 6 women), drink at levels that increase the risk of harm to their health. For men, that would be 5 or more units per day on a regular basis and for women, 4 or more units. So even if recent trends are going in the right direction, there are still far too many people whose drinking habits put them at risk.

In fact, the number of people being admitted to hospital where alcohol is the main reason for the admission rose in the latest year.

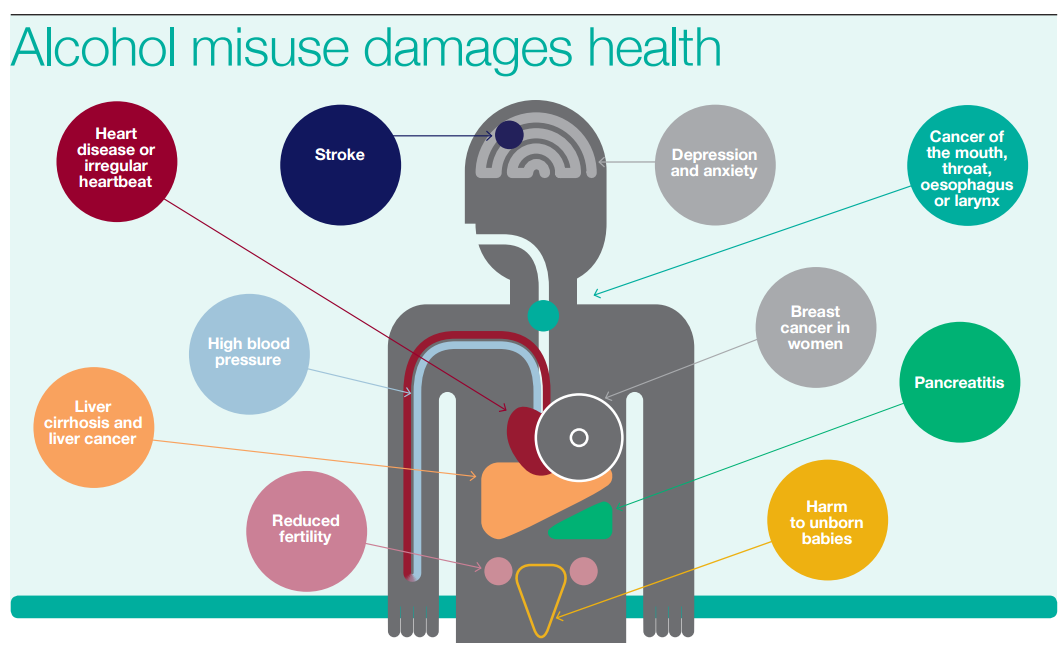

There were more than one million alcohol-related hospital admissions in England in 2013/14. Alcohol is one of the leading risk factors for early death and disability and for men under the age of 60; it’s actually the biggest risk factor for death.

It’s implicated in many diseases, including liver disease, some cancers, stroke and depression, as the infographic below describes.

The impact of alcohol, though, goes beyond health. It carries a heavy financial burden: £3.5bn in direct costs to the NHS and £21bn to society.

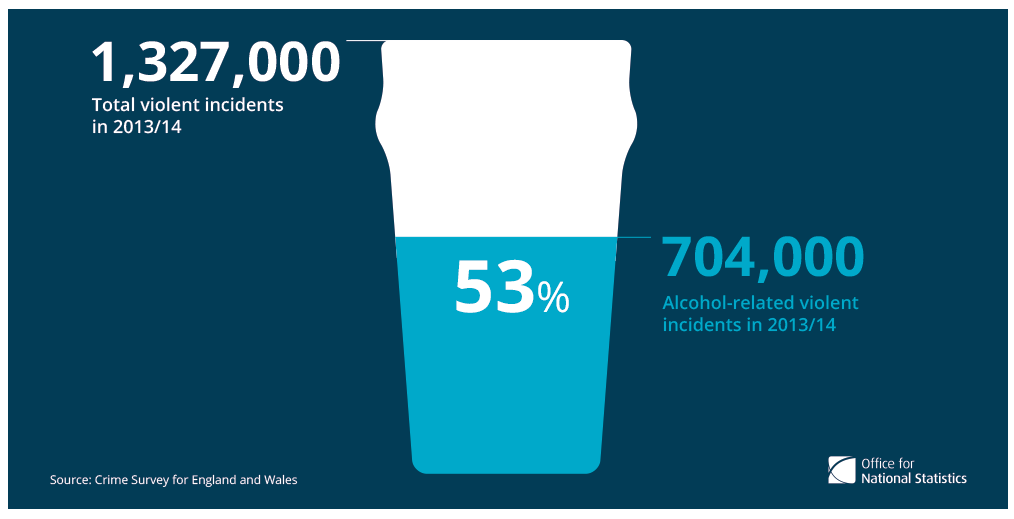

Societal costs are heavy – from education to crime. Over half of violent incidents involving adults were alcohol-related according to the Crime Survey for England and Wales (see infographic below) and 27% of social services serious case reviews involve alcohol misuse. Almost half of young people excluded from schools in the UK are regular drinkers.

Another cause for concern is that the positive trends we’ve seen around alcohol consumption often mask a more complicated reality.

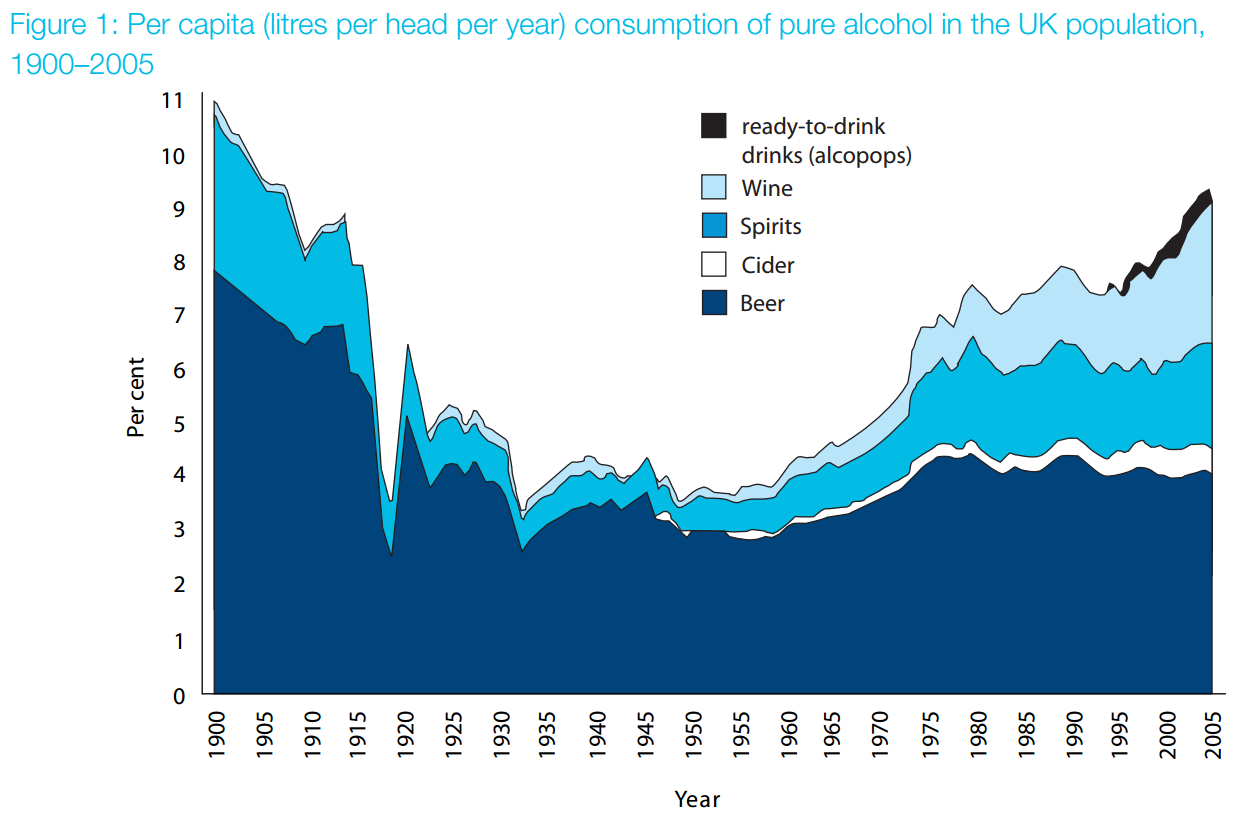

It’s true that we’re drinking less, on average across the population, since 2005. But the numbers look a lot worse if you step back further in time. The chart below shows the more than doubling in units of alcohol consumed per person since the 1950s.

Above: From Drinking in the UK: An exploration of trends by Lesley Smith and David Foxcroft, published in 2009 by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Reproduced by permission of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

And by including the teetotallers in the overall consumption trends, we risk under-appreciating how widespread excessive drinking is.

So among adults who had drunk alcohol in the last week, 55 per cent of men and 53 per cent of women drank more than the lower-risk daily amounts in 2012. Data from HM Customs and Excise also show that, for adults who drink, the average weekly consumption exceeds 21 units – which is above the lower-risk limit for men.

Furthermore, for conditions like liver disease, the statistics are alarming. The majority of deaths from liver disease are linked to excess alcohol consumption and the most deprived areas in England experience double the rate of deaths from chronic liver disease than the least deprived.

Since 1970, the death rate for this disease has risen by nearly 500% in patients under 65. This is particularly shocking given that we’ve managed to reduce mortality from other preventable diseases, such as heart disease, stroke and lung cancer.

Taking action

So there’s a compelling case for action. But to be effective, we need actions that target the alcohol harms themselves as well as the wider environment that gives rise to harmful drinking.

This wider environment includes complex and interrelated influences (social, legislative, economic and commercial) that shape people’s attitudes and behaviours towards alcohol. These provide many opportunities for change, but some interventions will have more impact at a national level, while others require a local context.

The affordability and availability of alcohol are key features of the alcohol environment. Both have increased over the long-term. Alcohol (as measured by a basket of alcoholic drinks) was around 60% more affordable in 2013 compared with 1980.

PHE continues to set out the evidence for the introduction of a minimum unit price (MUP) for alcohol. It is updating the latest data and modelling on MUP.

Alcohol has also become more widely available and this is an area where PHE is working with others, such as the Home Office and local authorities. There are examples across the country - from Lambeth, Blackpool, Liverpool and Bury - where location-specific intelligence (data on alcohol-related violence and public disorder, levels of deprivation, hospital admissions, and pupil absences) is helping to make the case for public health as a consideration in licensing decisions.

Population-wide measures are the cornerstone of primary prevention but targeted interventions are also needed.

The evidence of what works is there. Alcohol Identification and Brief Advice (IBA) interventions, for example, are structured ways to deliver advice and help to people who are drinking above lower risk levels. Their effectiveness has been shown in trials and systematic reviews and their cost-effectiveness has been modelled.

Of course, implementation is not straightforward and there are barriers that range from protocols to staff attitudes.

PHE is helping by developing tools that support professionals in understanding and delivering best practice.

The challenge of expanding prevention and intervention is spurring on new ways of working. In Blackpool and Middlesbrough, IBA is being delivered in a range of settings, from pharmacies and housing services to the fire service.

Alcohol care teams in hospitals are creating partnerships between specialties and working across mental health trusts, primary care, community teams, housing and social care. Examples include Nottinghamshire’s alcohol-related Long Term Conditions team and the Royal Bolton Hospital alcohol care team.

National campaigns can be powerful tools to shift habits and ‘reset’ people’s relationship with alcohol. The Dry January campaign, run by Alcohol Concern, and this year supported by PHE, encouraged a record 50,000 people to register. Last year, an evaluation found that the majority of those who began Dry January completed the month’s challenge and over 70% of participants managed to keep to reduced levels of drinking six months on.

In the next few months, PHE will produce a report for the Government on the public health impacts of alcohol and on evidence-based solutions.

We know why we need to take action and increasingly, we know how. Our ambition is that with our partners, we can forge a new approach; one that draws on the combined efforts of government, local authorities and the NHS to implement what we know works to reduce alcohol harm across our population.

3 comments

Comment by DC Vapor posted on

Nice posting about alcohol disadvantages. People should be aware about the bad effect of drinking because it causes cancer and other diseases.

Comment by dcvapor posted on

Drink alcohol in a high level harmful for your health . we need to take action to stop drinking alcohol in a high level. We should aware people about its diseases.

Comment by Ravi posted on

Great update, would be helpful to have a print function!