One of PHE’s roles is to reduce the often large health inequalities that exist between the most deprived and the least deprived groups in England. A group suffering significant health inequalities are people in prisons and other places of detention, such as police custody suites and young offender’s institutions.

This group experiences a higher burden of chronic illness, mental health and substance misuse (drugs, alcohol and tobacco) problems than the general public. Members of this group often come from already marginalised and underserved populations in the wider community.

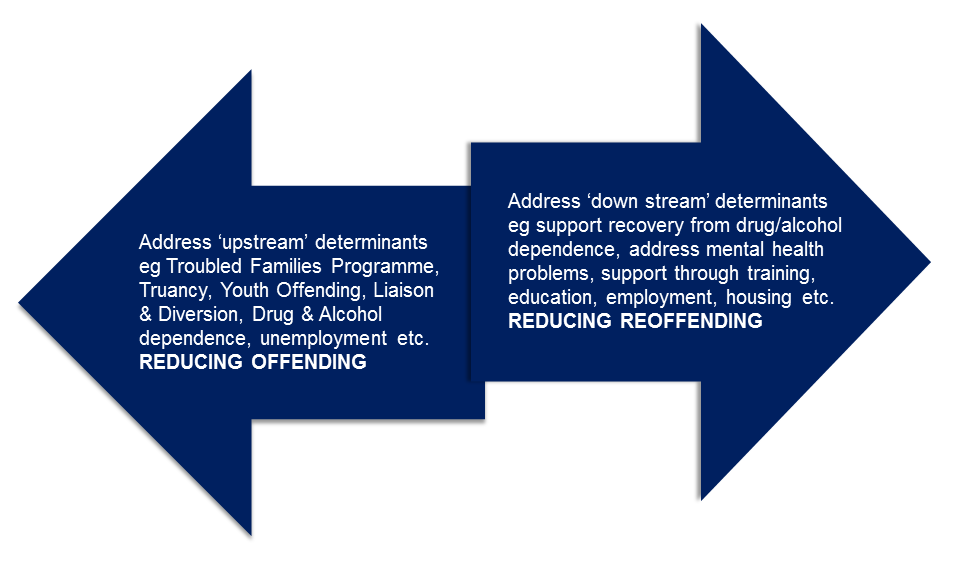

Figure 1: Public health model for health and justice

This is also a large group. The prison population is around 85,000 at any given time but in 2014 the total number of new receptions amounted to 204,941 . This vividly illustrates how the prison population is highly dynamic – with people moving not only between prison sites but also between communities and prisons.

This presents a challenge - how do you improve the health of a large, highly mobile group when an intervention may not be complete or successful before a person returns to the community?

Despite this, prisons and other places of detention offer a critical opportunity for tackling health problems in a way that can deliver benefits to the people and places they return to. We call this the community dividend.

Figure 2: Community dividend for public health interventions in prison populations

How does this dividend work? For a start we know health is often interlinked with offending and reoffending behaviour – especially for those with alcohol or drug dependence.

There is a strong link between alcohol and crime, disorder and anti-social behaviour, with alcohol being a factor in an estimated 47% of violent crimes. Drug users are estimated to be responsible for between a third and a half of acquisitive crime (shoplifting, burglary, robbery, car crime, fraud, drug dealing), yet treatment can cut the level of crime they commit by around half.

Therefore, by addressing dependence in a prison setting we can both improve health and reduce offending, leading to obvious societal benefits.

To deliver a community dividend and protect the health of the public, it is critical to test for and treat infectious diseases within prisons and other places of detention to prevent spread of these diseases in public.

We are world leading in our ability to collect surveillance data on infectious diseases from the whole English prison system in near real-time, allowing prison healthcare teams to quickly identify and respond to emerging threats.

Figures from last year show that viral hepatitis cases accounted for over 90% of all infectious diseases prison reports. This high proportion is partly the result of the introduction of opt-out testing for hepatitis and other blood borne viruses (BBVs) in prisons, leading to many more being tested.

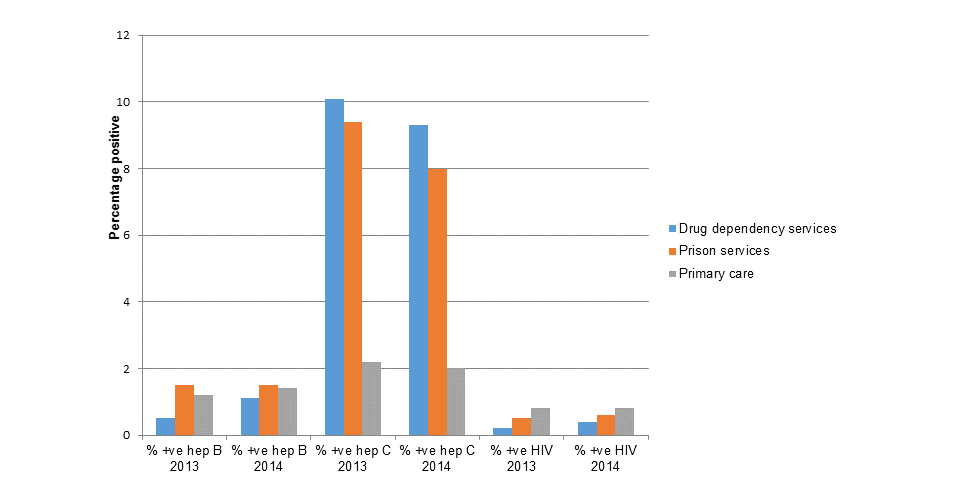

Infection rates among prisoners are significantly higher than the general public so prisons are clearly an important setting for testing and treating people for BBVs. However, prior to the opt-out approach, levels of testing among people in prisons were significantly lower than in the primary care or drug treatment services, making it possible that a prisoner infected with a BBV could return to the community still unaware of their infection, meaning they miss the opportunity to benefit from treatment and risk spreading infection to others..

Figure 3: Percentage of individuals testing positive for a BBV during 2013 and 2014

Source: PHE sentinel surveillance of BBV testing, all age groups

As a result we are rolling out a nationwide ‘opt-out’ scheme to increase the numbers of prisoners being screened and treated. Preliminary results from prisons who have already introduced the ‘opt-out’ policy reveal a near doubling of BBV testing. When Hepatitis B vaccines were introduced to prisons we saw a drop in rates in the public, our aim is to achieve the same success with other BBVs.

While detention can impact positively on the health care needs of many people this effect often only lasts for the period in prison. Perversely, a return to the community can result in reversing previous health gains, particularly engagement with health services. A lack of access to preventative health services like screening, immunisation and chronic care can worsen existing conditions and increase inequalities further.

Local authorities therefore have a vital role to play in ensuring continuity of care. In total 39% of local authorities have prisons within their area but all local health bodies have a responsibility for people in their communities who are in contact with the criminal justice system. We will continue to work with local authorities to help them best understand and respond to the issues that arise from health and justice.

If you are interested in delving further into these issues, our 2014 report provides an effective overview of the key changes in the health and justice system and discusses these health issues in more detail. On a more regular basis you can keep up to date with the PHE Health and Justice team’s progress and latest projects via our quarterly publication Infection Inside.

The focus in 2015 will ensuring that the key public health issues affecting this group are being identified and sufficiently robust plans are being developed to meet them at various levels across the country. Such plans require a variety of local and national organisations to work together across jurisdictions but the benefits of this to the public are truly significant.