The rising level of obesity is one of the biggest challenges that we face as a country and an important role for PHE is to advise the public - and the Government - on what constitutes a healthy diet.

Of course, there is a lot of advice already out there from expert clinicians or academics, but also from various people with an interest in this area, including commercial interests.

It can certainly be confusing for members of the public to know what they should and shouldn’t be eating, and in what amounts. From saturated fats to sugar – it can often feel like navigating a minefield of inconsistent nutritional advice.

It’s important to remember that information referred to as ‘expert advice’ is sometimes based on evidence that has known limitations. For example, it may involve a small sample of participants or ignore other factors that could affect the results.

Public Health England is committed to supporting the public to make healthier choices through the provision of credible advice based on the best possible evidence. So what exactly do we mean by that?

When we produce new guidance on a particular topic, our independent experts review all the available evidence on that subject – often hundreds of scientific papers.

We run full-scale consultations and go to great lengths to ensure that the evidence is considered fairly on its merits and without bias.

For example, PHE’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition produced new recommendations on carbohydrates, including sugars and fibre, in July last year.

The committee selected more than 600 peer-reviewed scientific papers for review, which were considered to be properly robust, out of an even longer list of studies. We also ran a full-scale public consultation.

Our approach to heathy eating advice

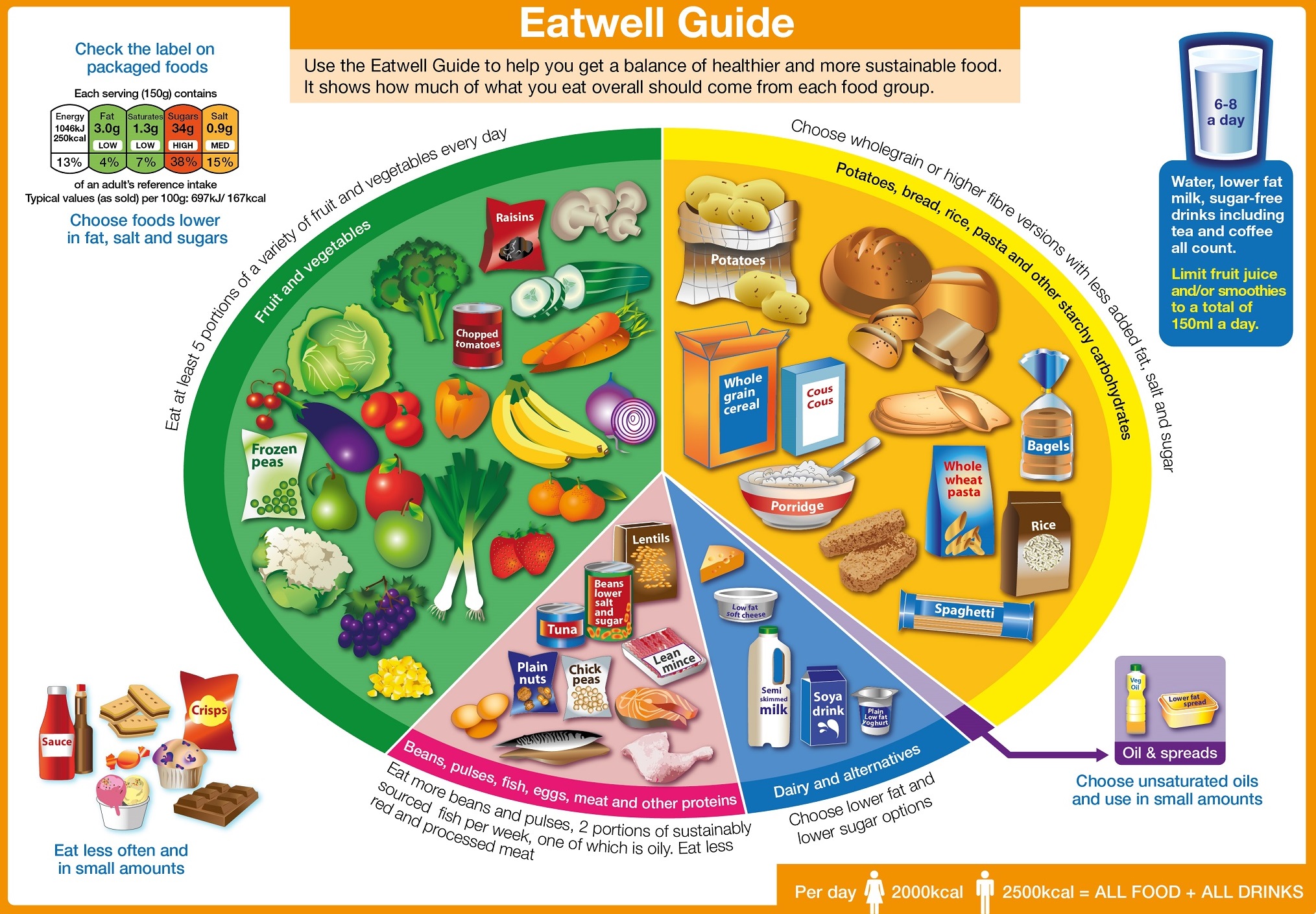

Another example of an evidence-based approach to producing dietary advice is the recent refresh of the Eatwell Guide. The eatwell plate was first introduced eight years ago to illustrate a healthy and balanced diet, and was updated earlier this year following some important developments in the evidence.

As part of this work we engaged with interested organisations and individuals through an external reference group and a public consultation with stakeholders, including academics, clinicians, non-profit organisations, commercial companies and industry representatives.

PHE has been criticised by some for working with industry on this guidance. However, the companies that supply our food have a major influence on what we eat, for example on how much sugar we eat.

The evidence shows that lowering the sugar content of the food and drinks offered in shops, restaurants, takeaways and the many places we eat could be a successful way of changing how much sugar the population consumes.

This has already been demonstrated through work to reduce salt consumption in the UK. Engaging proactively with industry was key to the success of that work.

Our analysis shows that a similar programme to reduce the levels of sugar in food and drinks would significantly lower sugar intakes, particularly if accompanied by reductions in portion size. In our view success depends on effective engagement with industry right from the start.

Although we have consulted industry and others on implementation, the underlying guidance behind the Eatwell Guide was not driven by the needs of industry.

It is entirely in line with the evidence and with advice from the World Health Organization and other government bodies worldwide. The modelling we used was commissioned by PHE from the University of Oxford, who have an international reputation for work of this kind.

But we know that one resource alone, such as the Eatwell Guide, is not enough to change the amount of food and drink consumed across the population.

Individuals, families, communities, the food industry and local and national government all have a role to play in tackling the obesogenic environment.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e27s1jOiH3I

We are working to support this in a number of ways in partnership with government departments and local authorities – from making it easier for people to take part in physical activity to supporting behaviour change through public campaigns such as One You and Change 4 Life.

Alongside a number of upcoming reports, we are working to review the evidence on saturated fat and health through the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition.

We hope to share a draft report for consultation next year – after we have reviewed and evaluated the entire body of evidence. All comments are welcomed and we hope that this comprehensive review of the evidence will continue to add clarity for the public on healthy eating.

We will continue to strive to give the public clear and actionable advice based on the best current scientific evidence.

11 comments

Comment by George Bekes posted on

I would like to ask Dr. Alison Tedstone, the Chief Nutritionist at Public Health England, how will she describe the reason for advising the high carb eating regime for the past 30 years when it has been known that sugar - a disaccheride - is detrimental to effective weight control but starch - a condensed form of sugar, polysaccharide - is recommended for 30% of the daily intake of food? Also, after many thousands of scientific studies that have taken place during the past 30 years, not one single effective counter measure has emerged against the concurrent rise of the epidemic of obesity? I await her answer with great interest.

Comment by Dr Louis Levy, Public Health England posted on

Levels of obesity are not decreasing because people aren’t following dietary advice not because the advice is wrong. Data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) shows that we are consuming too much sugar, saturated fat and salt and not enough fibre, fruit and vegetables and oily fish. (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-results-from-years-1-to-4-combined-of-the-rolling-programme-for-2008-and-2009-to-2011-and-2012). The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN), a committee of experts who advise PHE on nutrition issues, recently reviewed the totality of evidence on carbohydrates and health. It advised that ‘there needs to be a change in the population’s diet so that people derive a greater proportion of total dietary energy from foods that are lower in free sugars and higher in dietary fibre whilst continuing to derive approximately 50% of total dietary energy from carbohydrates’. Obesity is a complex problem; there is broad consensus that it is the result of a large number of factors, which are typically interlinked. Therefore, multiple policies and actions are required within and across settings, and at various system levels, to target the wide range of causal factors.

Comment by Adam posted on

Where is this list of 600 publications that were consulted in this project? And also the larger list this was selected from? Also, what exactly was the peer review process?

As a public body you should be transparent enough to release this information. Or is it already available? If so, where?

Please let me know.

Comment by Dr Louis Levy, Public Health England posted on

SACN’s Carbohydrates and Health Report is published on the SACN website https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-carbohydrates-and-health-report . The publications considered in the report are cited in the reference list. The additional studies mentioned are cited in the supporting documents, which can be accessed immediately below the report on the gov.uk page.

Comment by Dr Susan McGinty posted on

NHS Choices touts the Eatwell Guide as for those who are healthy or overweight. SACN is very clear (S.19) that the recommendation to replace 5% energy from free sugars by starches would "only apply to those people who are a healthy BMI and in energy balance". Can you please therefore confirm that the Eatwell Guide is only designed for those who are not overweight? For those who are overweight or T2D, SACN's advice is clear that a reduction of free sugars would be part of a strategy to decrease energy intake. SACN is very precise on this.

Thank you.

Comment by Dr Louis Levy, Public Health England posted on

You are correct that SACN’s advice applies to those who are a healthy BMI. In those who are overweight SACN recommend that ‘the reduction of free sugars would be part of a strategy to decrease energy intake’. The Eatwell Guide is a food selection tool aimed at all individuals over the age of 2 years. The Guide demonstrates the proportions in which foods and drinks from each of the 5 main food groups should be consumed in order to achieve a healthy, balanced diet. For those who are overweight, total energy consumption should decrease to achieve a healthy weight; however, the proportion of the overall diet that comes from each of the food groups should remain in line with the Eatwell Guide, which depicts a diet based on fruit, vegetables and wholegrain starchy carbohydrates.

Comment by Dr Suan McGinty posted on

Then why did SACN draft it in such a way? Surely all they had to do was make their general recommendation about 5% energy from free sugars being replaced by starch and that those who are overweight should follow a strategy for overall reduced energy intake.

It beggars belief that we are awaiting a Government Obesity Strategy when those who are overweight are actually being told to each more starch. Why could the recommendation for 5% energy from free sugars be replaced by non-starch vegetables? Or would that have mucked up the 5-a day programme?

SACN were very careful in their drafting. But then they have no control over the PHE Nutritionists do they? Are they accountable to anyone?

Comment by Miguel Toribio-Mateas posted on

Would you be so kind to clarify why the precise amount of wholegrain starchy carbohydrates? Wouldn't it be equally healthful for an individual to replace a large portion of those starchy carbohydrates with non-starchy ones, e.g. from increased vegetables (e.g. broccoli, cabbages, leeks, onions, etc.). The Eatwell Guide doesn't provide a clear route for this seemingly reasonable replacement? Just to make it absolutely clear, I am not suggesting wholegrain starchy carbohydrates are excluded, just wondering what drives PHE to prioritise them over non-starchy ones.

Many thanks in advance of your reply.

Comment by Dr Louis Levy, Public Health England posted on

In the report Carbohydrates and Health, SACN recommend that total carbohydrate intake should be maintained at a population average of at least 50% of total dietary energy. Recommendations on dietary fibre were also increased to 30g per day and advised to be sought from a variety of food sources; particularly wholegrain foods, as they are associated with lower cardio-metabolic disease and colo-rectal cancer. Wholegrain starchy carbohydrates make a significant contribution to dietary fibre intakes.

The Eatwell Guide was modelled using a linear programming method which measures the divergence of the recommended diet from the diet currently consumed, while taking into account nutritional and other constraints. Minimising the divergence of the recommended diet from the diet currently consumed is important to ensure the acceptability of the recommended diet with respect to palatability, cost, etc. In this modelling exercise, the SACN recommendations for free sugar and fibre were used as constraints, alongside dietary reference values for macronutrients and other government dietary recommendations including the consumption of at least 400g of fruit and vegetables per day (5 A Day). The Eatwell Guide was drawn based on the output from this modelling exercise, and depicts a diet based on fruit and vegetables (contributing 40% of the main image) and wholegrain starchy carbohydrates (contributing 38% of the main image).

Comment by Miguel Toribio-Mateas posted on

Dear Dr Levy, thank you so much for your reply.

You say that SACN recommend that total carbohydrate intake should be maintained at a population average of at least 50% of total dietary energy and mention the 30g per day of dietary fibre that should be obtained from a variety of food sources. Why particularly wholegrain foods? You mention that these are associated with lower cardio-metabolic disease and colo-rectal cancer. Are you suggesting that the sources I quoted in my original post (e.g. broccoli, cabbages, leeks, onions, etc.) aren't also associated with such benefits, or indeed that they do not make a significant contribution to dietary fibre intakes? Please be so kind to answer these questions.

You also mention palatability and cost as factors which have been used as constraints in your modelling exercise, which takes into account population averages. Does your modelling exercise take into consideration that individual preferences can differ from those of the "average" and that a growing number of individuals do not wish to have 38% of their "plate" filled by starchy carbohydrates from whole grains?

Dr Levy, I have myself seen 100s of individuals in my nutrition clinics whose cardio-metabolic markers (fasting glucose and insulin, glycated haemoglobin, LDL to HDL ratio, high sensitivity C-reactive protein, folate and vitamin B12, homocysteine and thyroid hormone markers including TSH, free T4 and T3, and thyroglobulin/peroxidase antibodies, amongst other) have improved dramatically by making the subtle changes I describe above. Additionally hundreds of peers (both in the UK and abroad) who investigate these markers routinely as part of their clinical practice have seen these changes too, simply by replacing some of the starchy carbohydrate with carbohydrate from the other sources I mentioned above. Yet we're being told our advice is "not evidence based" and indeed that it is "dangerous and irresponsible" because it doesn't follow the guidelines issued by PHE. Could you answer specifically on what grounds it would be dangerous or irresponsible to obtain one's carbohydrate, fibre, micro- and macro-nutrients from non-starchy vegetable sources versus starchy whole grains?

From your answer, it sounds as if PHE's guidelines are based on a theoretical, computer generated model which as a food selection tool is inappropriate for use with individuals. Are you suggesting that giving 38% of starch to an individual needing cardio-metabolic improvements, particularly if these individuals were overweight, obese, pre-diabetic or indeed diagnosed as diabetic (type 2), is better than giving them less (say half of that) and "top up" with vegetable, non-grain sources? Could you point me to irrefutable evidence that points to the absolute need for whole grains as opposed to more vegetables? Or to a study that has found this replacement to be dangerous.

I am grateful for your time and answers.

Comment by Dr Matthew S Capehorn posted on

I am the Clinical Director of the National Obesity Forum. The NOF would like to clarify that the document entitled, "Eat Fat, Cut The Carbs..." that has featured so prominently in the press over that last couple of weeks is not an NOF publication. It was co-authored by, among others, our Chair, Prof David Haslam, and the rest of the Board did not have any input into the content, or see the document prior to publication, and may have misled the press and public by being published with the NOF logo on it. The NOF would not normally support, or condemn, a document such as this, which is in essence and opinion article. The NOF is a "forum" that welcomes debate and discussion, even when opinions challenge wildly held beliefs, and this paper has some interesting arguments for future discussion. However, the Board feel that some of the statements in the document do not reflect the overwhelming body of evidence at present. It does not have a mandate from the NOF Board, let alone the membership, and therefore should not be viewed as a NOF policy or guideline. For further information regarding this document, enquiries should be directed to the authors.