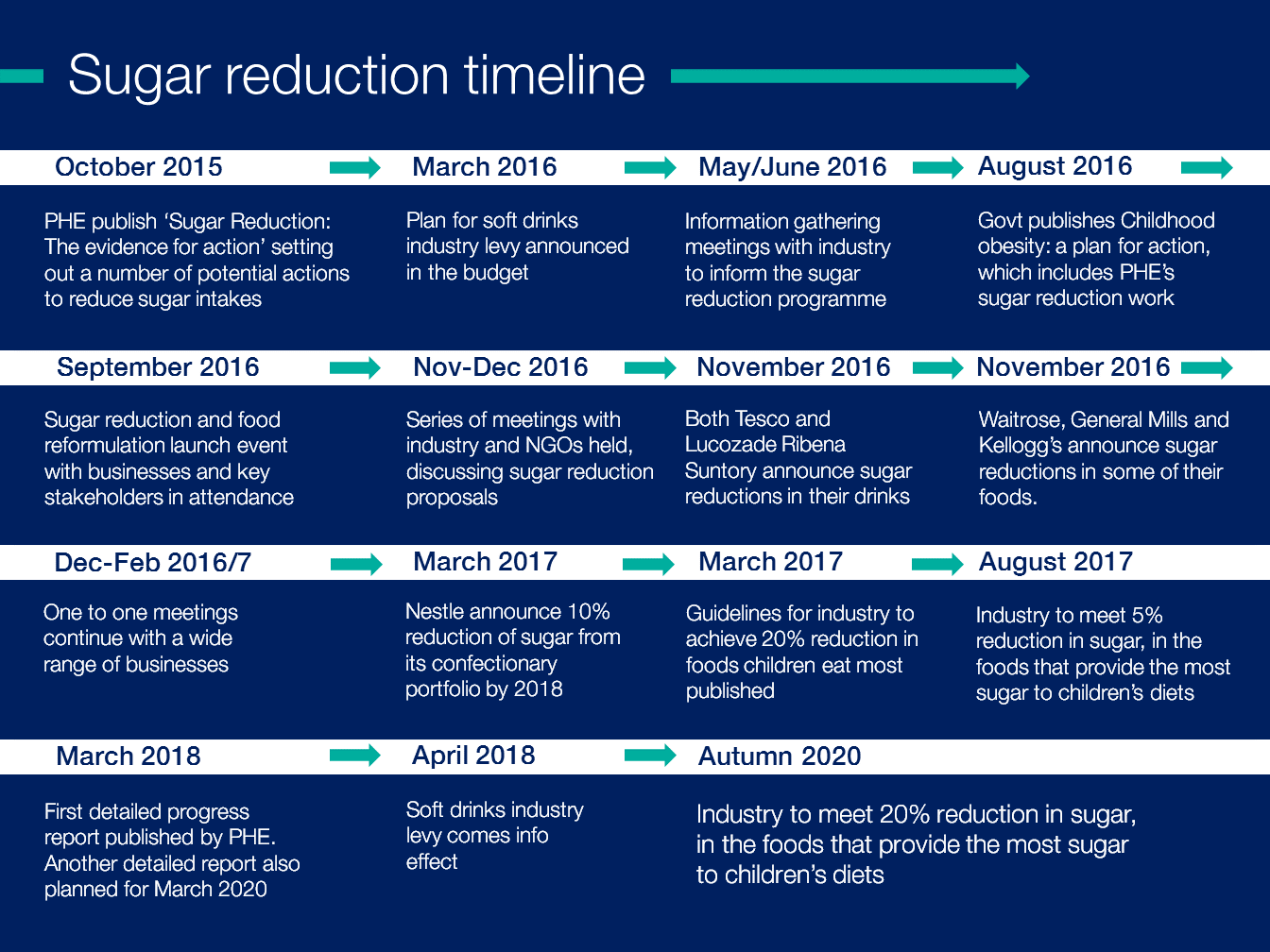

As part of our sugar reduction programme we’ve published new guidelines for the food industry demonstrating how they can remove 20% of the sugar in nine categories of food which contribute the most to children’s intakes.

In this blog, PHE’s chief nutritionist Alison Tedstone answers questions about this important milestone which supports achievement of the goals set out in Childhood obesity: a plan for action.

Can you explain what this new publication is?

This is the first technical report of the programme and sets the guidelines for all of industry, whether that’s manufacturers, retailers or the eating out of home sector (eg coffee shops, family pubs, restaurants, takeaways) on how they can reduce the amount of sugar our children consume from some key everyday foods.

These are the same foods consumed by everyone so this programme will benefit the whole family.

The guidelines are based on over six months of engagement with the food industry, public health campaigners and health charities and we’re now in a position where everyone can see what industry needs to do to achieve the Government’s target of a 20% reduction by 2020, with 5% in the first year ending August 2017.

What exactly has industry been asked to do?

The report goes into detail on how industry can go about removing sugar from broad categories of food that contribute the most to children’s sugar intakes (breakfast cereals, confectionery, ice-cream, yogurt, morning goods, sweet spreads, biscuits, cakes and puddings).

We’ll monitor the programme's progress by measuring the net amount of sugar removed from the categories using a ‘sales weighted average’ (SWA) baseline.

This provides a measure of the average level across the food categories weight by volume of sales that contribute the most to children’s sugar intakes.

This baseline shows the average level of sugar across the categories prior to the launch of Childhood obesity, a plan for action and our sugar reduction programme.

So high selling products with high sugar content will raise the average, while high-selling products with low sugar content will reduce it, meaning we should see more sugar reduction in high sugar, high selling products and a shift in sales to lower sugar options.

We’re using 2015 data as the baseline, which means any work industry has already done before this programme began can receive recognition. Significant work done earlier than 2015 will also be recognised when we look at progress in March 2018.

Industry has the flexibility to take a range of action including:

- Reformulating – that’s changing the recipe of a product to lower the levels of sugar

- Reducing the portion size, and/or the number of calories in single-serve products

- Shifting consumer purchasing towards lower/no added sugar products, introducing healthier alternatives and incentivising people to buy them

So for example for breakfast cereals, the current baseline across the category is 15.3g in 100g of product, and we have challenged industry to lower that to 14.6g by August 2017 and then 12.3g by 2020.

Is the food industry on board with this? Why should they go along with these guidelines?

We’ve had more than 40 individual meetings with food suppliers, manufacturers, retailers and the eating out of home sector, nine food category specific meetings and three meetings on data and we’re confident that industry will rise to the challenge.

Businesses have the flexibility of the three approaches and we know there is expertise to work towards the 5% and overall 20% target.

And many of them are already on this journey. Since ‘Childhood obesity: a plan for action’ was published, retailers and manufacturers like Nestle, General Mills, Tesco, Waitrose, Kellogg’s, Sainsbury’s, Marks and Spencer and Brecks Foods have announced they are, or already have, lowered the amount of sugar in their products.

The world is watching how the UK tackles obesity. Rather than this being seen as a negative for business, our food industry can innovate and be ahead of the game when it comes to creating healthier products that people around the world enjoy.

But what happens if the 20% sugar reduction by 2020 isn’t met?

Meeting the 20% target is ambitious but we believe it’s achievable. The Government has said that if enough progress isn’t made, other levers will be considered.

Do the public want changes made to their food?

The recent British Social Attitudes survey asked the public a range of questions about obesity and nine out of ten believed cheap fast food was too readily available and around half said unhealthy snacks should be made smaller.

A separate Which? survey found that half of the people surveyed wanted to see less fat, sugar and salt in their foods.

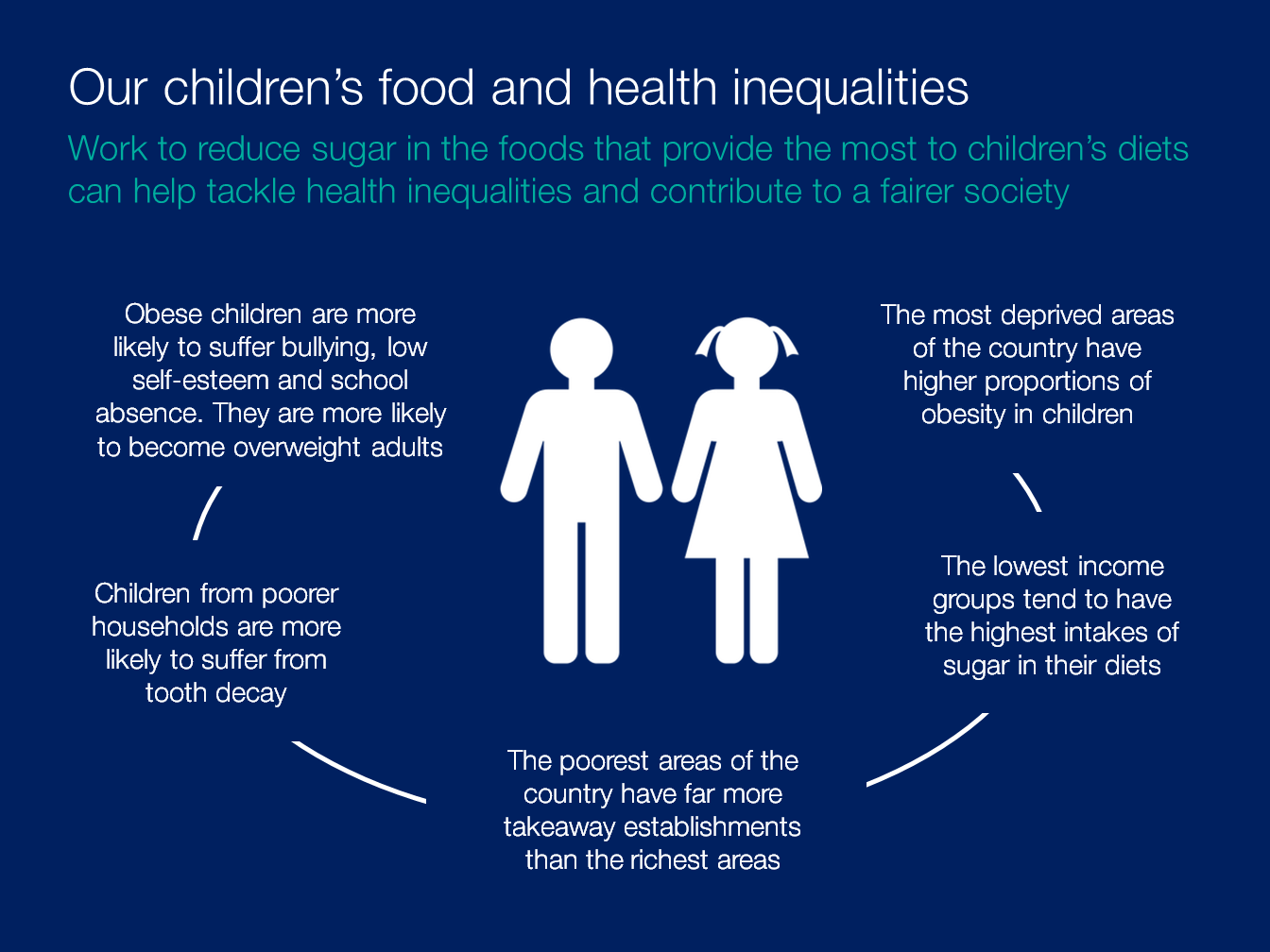

But we must focus on the reason this programme exists. Far too many of our children are overweight or obese and are likely to carry this health problem into adulthood, increasing their risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers.

Added to this, tooth decay is still one of the most common reasons for hospital admissions for children aged 5 to 9.

We also know our children are consuming three times the recommended amount of sugar.

Levels of obesity are higher in children from deprived backgrounds so tackling the amount of sugar we eat is not just a healthy thing to do, but an issue of inequality for many families.

Will this programme make food taste bland?

The sugar reduction process will happen gradually over the coming few years, so any change in taste is unlikely to be noticeable.

It’s important to compare this to the work on salt and the reduction of 11% in salt intakes. Over the years the government worked with industry to voluntarily reduce salt in everyday foods.

Many people don’t realise that 10 years ago a loaf of bread contained about 40% more salt than it does today – people didn’t notice this change.

But don’t forget, as well as changing the recipe of products, the food industry can also reduce sugar by reducing portion size or shifting overall consumer purchasing by offering healthier alternative options alongside existing products.

Will food manufacturers just use lots of artificial sweeteners if they reduce sugar?

Intense sweeteners that have been approved by the European Food Safety Authority’s processes are a safe and acceptable alternative to using sugar.

It’s up to the individual company if they use them to reduce the sugar content of their products but we understand that for many businesses there are issues of consumer acceptability. There are also issues around allowing people's palates to adapt to a slightly less sweet taste.

How will this programme affect venues like major coffee shops and restaurant chains?

It’s essential we see the same level of engagement from all including the ‘eating out of home’ sector as we do from food manufacturers and retailers.

Rather than being an occasional treat, eating out of home now accounts for a large proportion of the food we eat. In fact around 20% of meals were eaten out of the home during the year ending March 2015, a 5% increase on the previous year.

We’ve taken extra steps with this sector to encourage them to get on board and ensure a level playing field across all of the places we buy food.

What’s next for the programme?

PHE will provide information on the programme at 6 month intervals. We’ll publish detailed assessments at 18 and 36 months and use these to determine whether sufficient progress is being made by the food industry.

Later this year the programme will be expanded to include reducing total calories in a wide range of product categories across all sectors, including the eating out of home sector.

We will also continue to reinvigorate salt reduction and drive industry to meet the 2017 salt targets.

And work on saturated fat will be further reviewed in light of scientific recommendations, which are expected next year.

It’s also worth remembering that the sugar content of drinks is being addressed through the soft drinks industry levy, which was announced in the March 2016 budget. Any drinks excluded from the levy will become part of PHE’s programme.

But the results of the programme will take time to be seen. Looking further ahead, we hope to see the results of the sugar reduction programme reflected in sugar intakes reported in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey. The survey monitors dietary intakes of sugar (and other nutrients) in population age and sex groups over time.

1 comment

Comment by Marta posted on

I would like to know if the UK government is openly endorsing artificial sweeteners for children, because this is what it looks to me. Government should clearly voice their position in favour or against artificial sweeteners and take responsibilities for the future effect of these products on children's health.