Next week PHE will host our fifth annual conference at the University of Warwick. As we prepare to bring together the public health community I’m taking a look at three key topics which are at the forefront of public health and which cut through many of our conference sessions; the impact of world leading science on the public’s health, health inequalities and finally the economic case for prevention.

In this blog I'm looking at addressing health inequalities, which cuts across almost all that we do as a public health agency and indeed for all those working right across the sector.

When looking at inequalities we must consider many different factors, from housing, jobs and worklessness to geographical disparity and how all of these affect health and life expectancy.

You may have seen our first Health Profile for England published recently, which combines PHE data and knowledge on the health of the population in England and brings it together in one document for the first time.

The chapter of the report on health inequalities explains that there is social gradient to life expectancy.

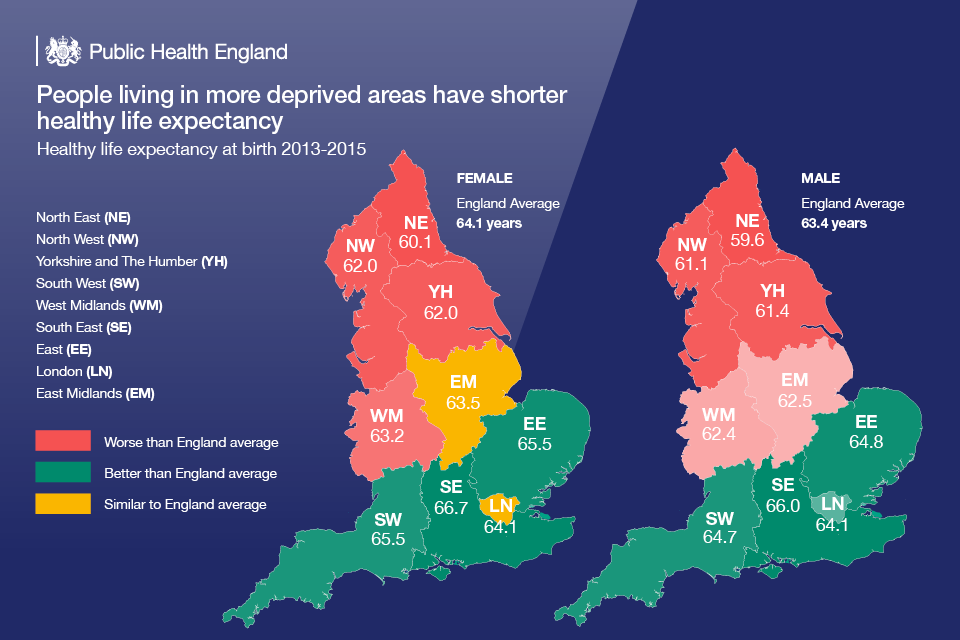

The data show people living in the most deprived areas in England have on average the lowest life expectancy and conversely, those in the least deprived areas have the highest life expectancy.

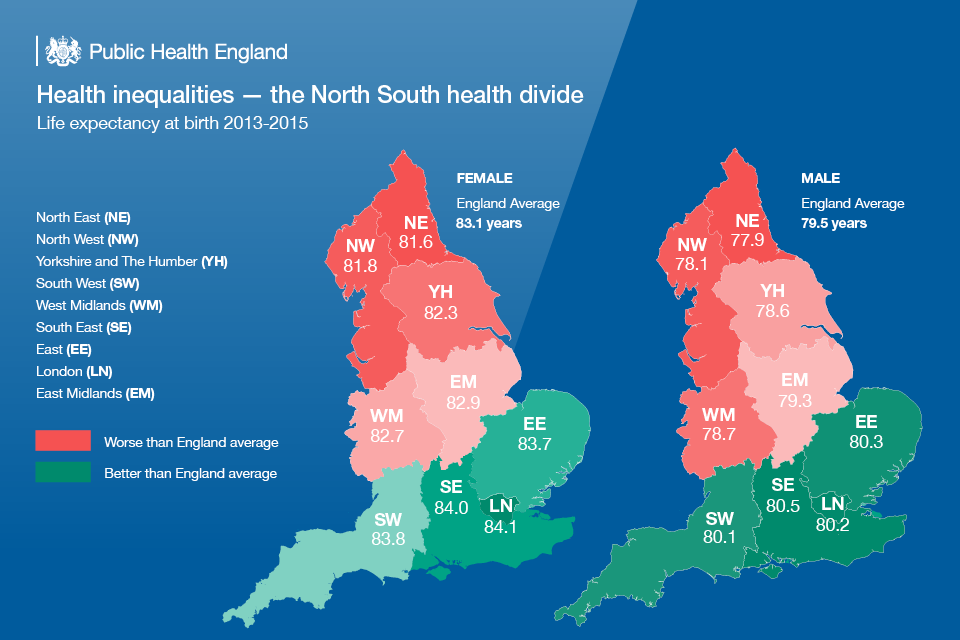

We also know that while deprivation can be found in all regions of England, there is a north-south difference in life expectancy.

People who live in southern regions can expect to live substantially longer and spend fewer years in poor health than those who are further north.

Closing this gap and reducing health inequalities is one the biggest challenges we face in public health and you can read more about the other factors affecting this, including gender and behavioural risk factors in the report.

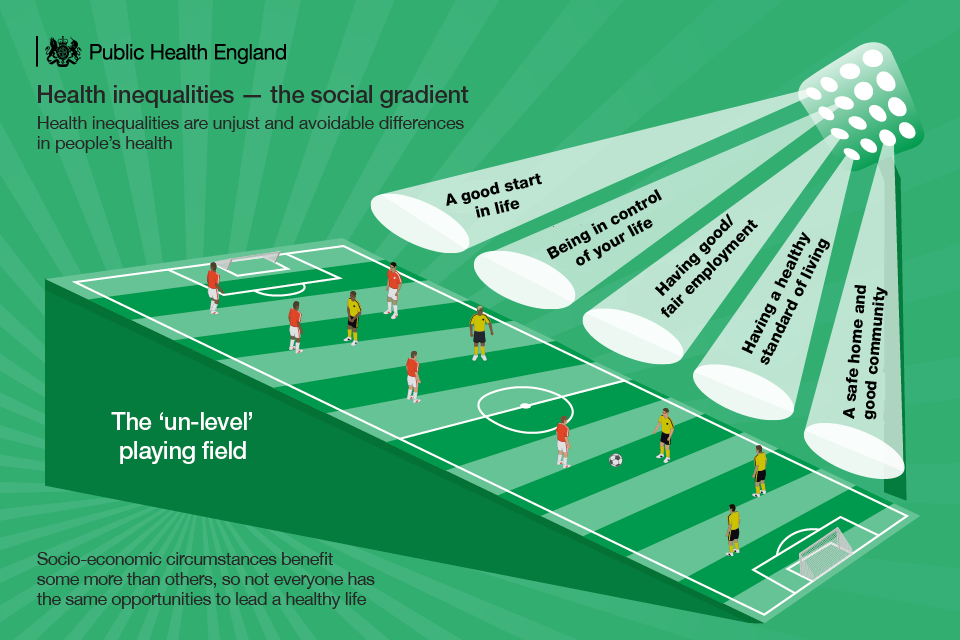

Health inequalities are underpinned by social determinants of health, which are determined by the broad social and economic circumstances into which people are born, live, work and grow old.

There is a social gradient across many of these determinants that contribute to health with poorer individuals experiencing worse health outcomes than people who are better off.

Children growing up in more deprived areas often suffer disadvantages throughout their lives, from educational attainment through to employment prospects, which in turn affect physical and mental wellbeing. This is covered in detail in chapter 6 of our Health Profile for England.

Alongside the Health Profile for England, we also published a report on health equity in England, which presents indicators for selected determinants of health, as well as health outcomes.

It also provides breakdowns of data across a range of determinants, which are referred to as dimensions of inequality.

Examples of these are personal characteristics, including age, sex and ethnic group, as well as socio-economic deprivation.

A key message of this report shows that despite the long term trend of improvement in life expectancy, infant mortality, and rates of premature deaths from cancer and cardiovascular disease in England as a whole since 2001-03, stark inequalities remain.

The only way we can tackle this is through joined up work between many agencies.

For instance built and natural environments are major determinants of health and wellbeing and through working with the Department of Communities and Local Government recently, improved guidance on health and wellbeing for planning in local authorities was published.

Planning in local authorities plays a key role in health and wellbeing and we must encourage efforts to create healthier food environments, planning proposals which promote healthy and vibrant communities, housing built with health in mind and healthy lifestyle opportunities.

The scope of health inequalities is vast, and work to reduce them is coming from right across the health sector from our colleagues in public health, the NHS and local government.

PHE has just produced a guide: ‘Reducing health inequalities; system, scale and sustainability’, which sets out actions that local health systems can take make an impact at population level, actions to achieve best population outcomes through services and includes tools and resources for planning these actions

Although we can only include a snapshot in this blog, there are plenty of resources and tools which are available for those working on this issue to get involved and informed.

We’d also like to suggest that those who are attending our conference and are interested in learning more and being part of wider discussions attend some of the sessions we have on this area.

These include a keynote on the north-south health divide, sessions on housing and health, health and closing the employment gap, improving life quality of older people and place-based public health. The full programme is available here.

Why not read our other pre-conference blogs on making the economic case for prevention and on the use of science to protect our health.