It’s been one year since the launch in the House of Lords of “Rebalancing Act”: a resource developed by PHE, Home Office and Revolving Doors Agency, to support a broad range of local, regional and national stakeholders in understanding and meeting the health and social care needs of people in contact with the criminal justice system (CJS).

The ultimate aim of the resource is to improve health, reduce health inequalities, drive down offending and reoffending and improve community safety.

For every person in custody, three more are on probation

The number of people in contact with the CSJ is far larger than the prison population. At any one time, the number of people using probation services outnumber those serving a custodial sentence by around three to one and nearly two million people a year in England have contact with police forces resulting in a record on the Police National Computer (PNC).

People in contact with the CJS face significant inequalities

In recent years there has been a growing awareness that people in contact with the CJS face significant health inequalities, including multiple and complex health and social care needs and this has an impact on the wider community they live.

Addressing these inequalities therefore has wider benefits – a community dividend – making it not only the right thing to do, but also the wise thing to do.

The links are complex but some health and social care needs are linked to offending behaviour (e.g. substance dependence, mental health, homelessness, being in debt) – we have the opportunity to ‘kill two birds with one stone’ and drive down offending behaviour and health inequalities by focusing on meeting these needs.

This can ultimately reduce cost for healthcare and law enforcement agencies and improve public safety; the ‘community dividend’ from the investment.

Health needs are further complicated by social issues

While evidence is of variable quality, the picture that emerges is that people in contact with the CJS often have high levels of health needs complicated by social issues such as unemployment, indebtedness, homelessness, social isolation, lack of training or education, and psychological trauma.

The low levels of help-seeking behaviour we see in this group are exacerbated by a range of other obstacles to effective engagement with services, sometimes including inaccessible, poorly designed and/or restrictive services.

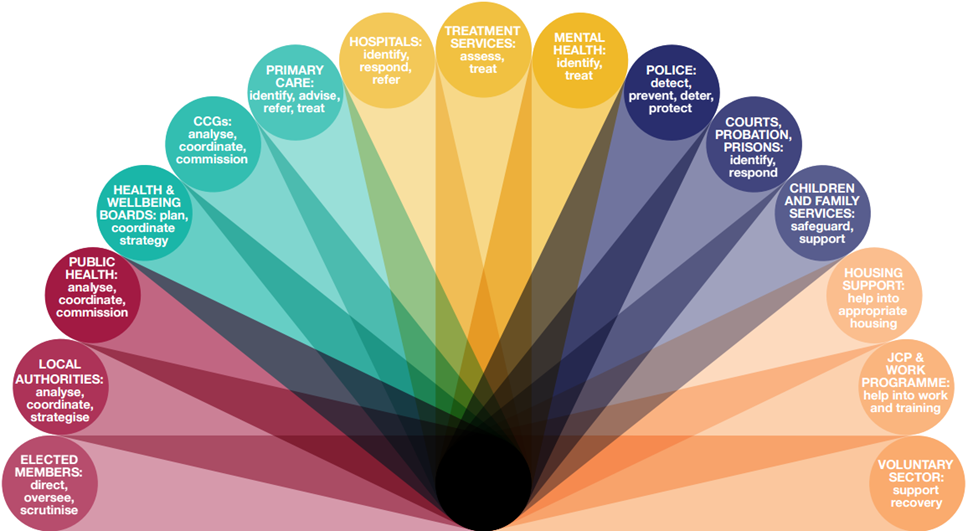

What we find is that because of this group’s “multiple and complex needs” there is typically not one agency or organisation working alone that can address those needs. As a result this population is often described as being ‘underserved’ i.e. services are not provided appropriately or accessibly to enable this community to benefit.

Therefore, bringing services closer to the people who need them may substantially improve uptake, presentation and utilisation, and patient pathways should be designed with this in mind.

Lack of data is one of our biggest obstacles

Rebalancing Act draws on a range of published data to illustrate needs and in doing so highlights one of the biggest obstacles in any attempt to redesign systems at a local level. Much of the data is incomplete, out of date, unpublished, or otherwise problematic.

It is also widespread, across Government statistical releases and reports, academic journals, and a range of other organisations including the police, probation, Jobcentre Plus, health services and local authorities. Partnership working is therefore central to assessing local need and planning of services, as well their delivery.

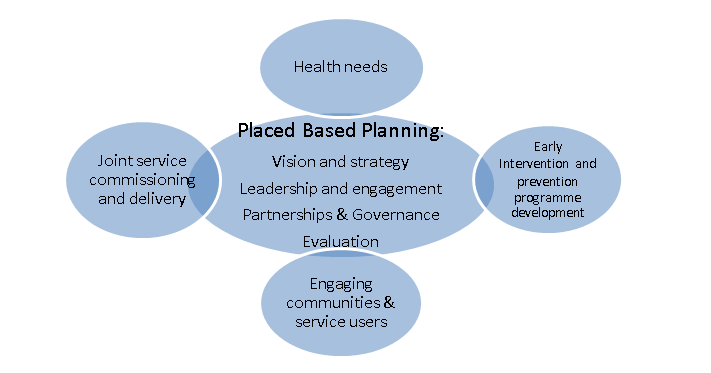

The resource proposes the development of a ‘place-based planning hub’ (See chapter 2 here), using an integrated local approach to bring together a coherent strategy which:

- understands the specific health needs of people in contact with the criminal justice system locally to inform local strategies and commissioning

- engages with communities through local services and networks that already exist locally

- enables joint commissioning and delivery of programmes with partners across the system: with a focus on preventing and reducing offending and improving access to healthcare and continuity of care between custody and community

Pilots and evaluation are key to future progress

To fill this ‘evidence-gap’ there is a need for innovation, robust evaluation, and sharing learning locally and nationally. Good evidence to support a range of interventions and treatments is available for substance misuse, mental and physical health problems and for aspects of offending and reoffending the evidence is dynamic and evolving.

However in other areas, such as employment or housing support, the understanding of ‘what works’, what is effective and cost effective, is less developed.

Innovation often involves risk, including the risk of failure, and early intervention may save public money, reduce inequalities and improve lives, but it may struggle to generate rapid cashable savings. Piloting, and robust evaluation, can make the case for new interventions and programmes.

One example of this type of work comes from the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA).

They are developing a system wide health and justice strategy which is being jointly led by themselves, the mayor’s office and Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership.

This will test new ways of working and good practice will be shared with other areas. Most importantly this will include quantifying the benefits, particularly the financial return for the community i.e. the community dividend of this approach. We look forward to seeing the results from this work.

In conclusion, the essential ingredients are:

- a clear vision of what is to be achieved

- strong leadership at local level

- effective collaboration across not only health and justice organisations but also local government and third sector organisations

We are hopeful that through effective collaborative working, sharing information, or even through pooling funding, it will be possible to deliver services and preventative programmes that are not only more efficient and effective, but also more cost effective.