You don’t have to dig too deep into the statistics to see how homelessness affects public health, but it can be difficult to work out what to do about it. A new review from Public Health England South East shares information and support to help local authorities prevent and reduce homelessness.

Homeless men and women die young – by an average age of 47 for men and 43 for women. This compares to 79.5 for males and 83.1 for females in the general population.

An estimated 41% of people classified as ‘rough sleepers’ have long-term physical health problems such as heart disease, diabetes and addiction problems, compared to 28% of the general population. Another 45% have been diagnosed with mental health issues, compared to 25%.

It is easy for us to feel the emotive punch when walking by someone living on the street – but harder to know how to help. We worry about hunger, so buy a sandwich and/or a cup of tea. We worry about cold, so collect hats or blankets. Sometimes we just give change.

For local authorities with rising homeless populations the quandary about what they can do is not only an emotive and moral one, but since the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 became law last year, also a legal one.

The new Act will come into force in 2018 and will place a statutory duty on LAs to prevent homelessness and support all those requesting help who may be at risk of homelessness, irrespective of whether or not they are in the groups which previously allowed them to prioritise. Authorities are also under increasing pressure from members and the public to reduce homeless numbers and provide for the health and social needs of this growing population under their care.

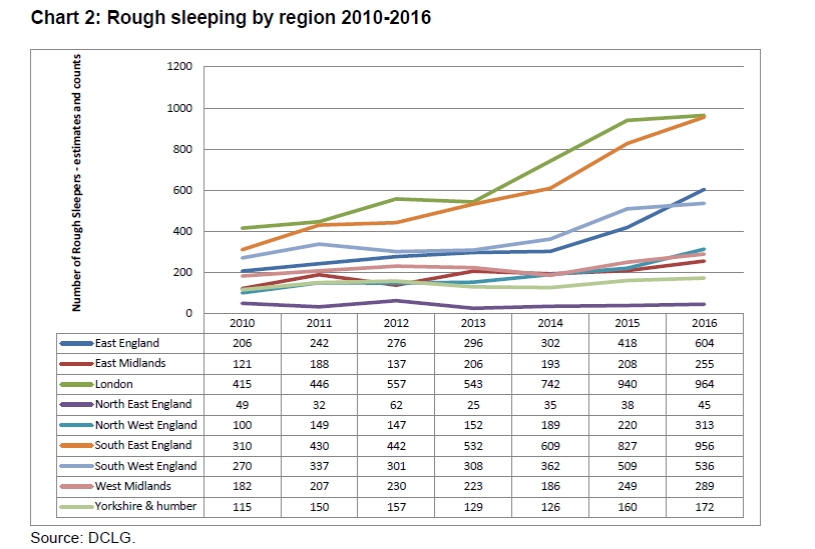

These are difficult challenges considering the lack of available and affordable housing; changes to the benefits system; the financial pressures which councils are under and other risk factors. Especially given that homelessness in the UK, and in particular in London and the South East, has been increasing since 2010 and is predicted to continue to do so.

Some authorities came to PHE for help and as a result, an evidence review: Adults with complex needs (with a particular focus on street begging and street sleeping): has just been published.

Aims to

This review aims to provide an independent voice and focuses on those who are street homeless and/or who street beg. It looks at existing data, the reasons why people may become homeless, possible solutions and highlights where work needs to be done.

It includes:

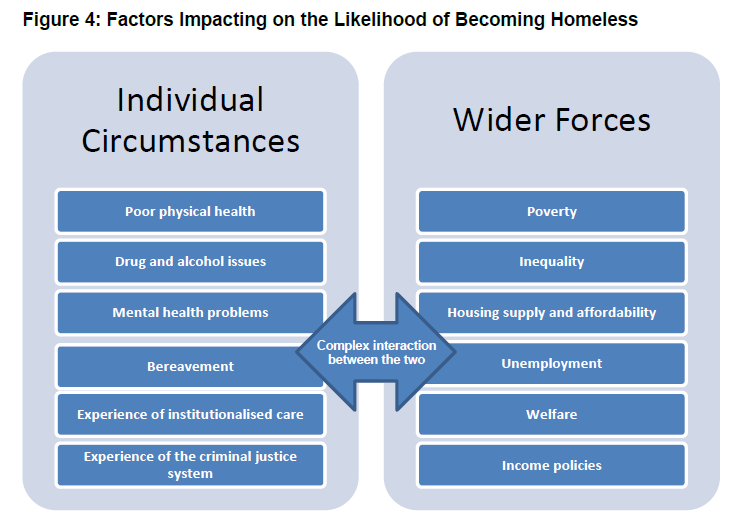

- An analysis of the homeless – including the risk factors for becoming homeless, the level of vulnerability of the homeless and the range of health and social needs they may have

- An analysis of the pattern of homelessness across the UK – including the numbers of people who sleep rough and where people sleep rough

- Interventions which look promising and evidence of what initiatives may work to reduce or prevent homelessness

- Some tools and guidance to help local authorities develop their plans

Evidence

Evidence in the review shows it is harder for the homeless to access the health and social care services that others do. This is often because services are separate and disconnected, making it difficult for people to navigate and use.

Many are vulnerable adults with complex needs suffering with mental health issues and / or substance abuse, yet they cannot access the services they need to get better. Many have physical health issues, which are compounded by the living on the streets.

The evidence also shows that homelessness is:

- Mainly in urban and tourist areas. Cities in the South East with particular issues include Brighton and Hove, Canterbury, Portsmouth, Oxford and Maidstone.

- Likely to be vastly underestimated – numbers are calculated very roughly and do not capture the ‘hidden homeless’ like those who sofa surf.

- Caused by a complex mix of issues stemming from early childhood experiences to the development of substance misuse and mental health problems. Often the catalyst is leaving an institution such as prison or hospital, or being thrown out of the family home.

- A bigger problem the longer it goes on – the longer people are on the street, the more their issues spiral

Conclusion

This review does not have all the answers to homelessness – nor could it – but hopes to be a first step in providing support and information for the growing number of authorities struggling to know how to cope.

It recommends the key issues highlighted and evidence collated is used to help localised situations, and that the gaps in research/evidence and data identified are filled.

It finds that integrated working is vital – with services working together to help those leaving prisons and hospitals, and prevent vulnerable individuals falling into rough sleeping. It also finds that prevention in all its forms is key – and that focus at the point of homelessness is often already too late.

Most of all it highlights the ethos is that everyone has a right to both physical and mental healthcare whoever they are – but that for the homeless it is harder to access. Let’s work together to change this.