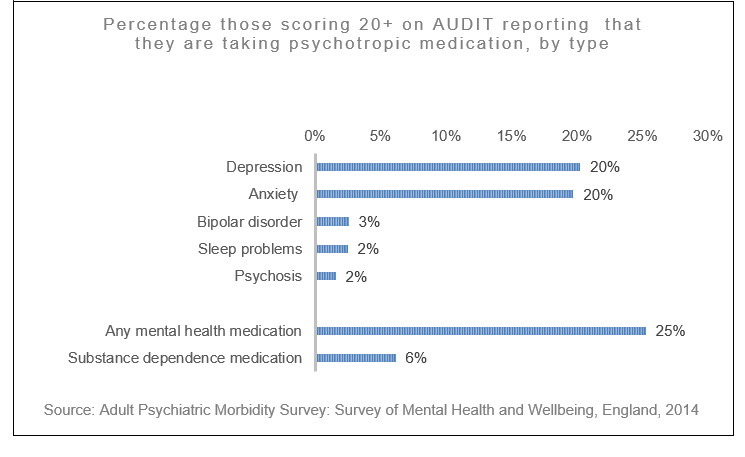

There are an estimated 589,000 people who are dependent on alcohol in England and about a quarter of them are likely to be receiving mental health medication; mostly for anxiety and depression, but also for sleep problems, psychosis and bipolar disorder.

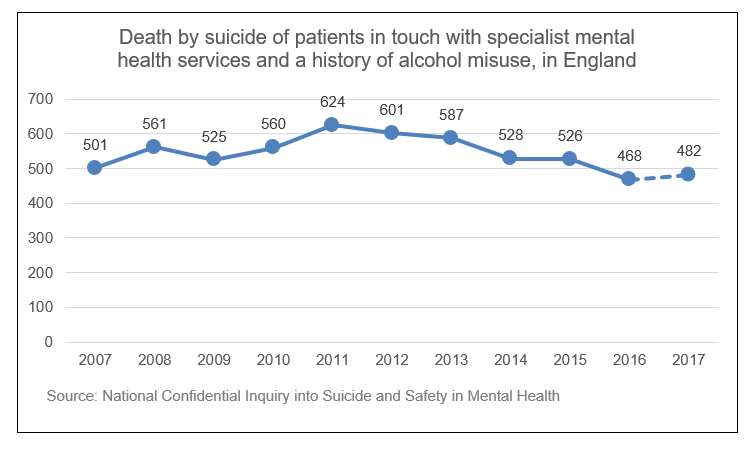

Deaths by suicide amongst mental health patients

People in touch with specialist mental health services who also have a history of alcohol problems can be at elevated risk of death by suicide. Between 2007 and 2017 there were 5,963 suicides in mental health patients with a history of alcohol misuse, an average of 542 deaths by suicide per year – about 10% of all deaths by suicide in England.

NHS Trusts that have put in place a policy on the management of patients with co-morbid alcohol and drug misuse have reduced rates of suicide by patients by 25%.

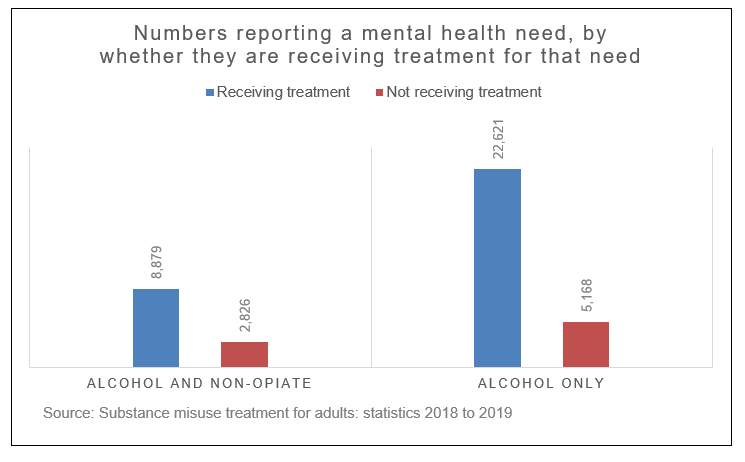

People in alcohol treatment

Data collected from over 72,000 people in alcohol treatment last year shows that more than half (55%) expressed a need for help with their mental health, and four in five (79%) of those said they were receiving some support. Accademic evidence suggests that the proportions of people in the alcohol treatment system with co-occuring mental ill-health is likely to be higher.

However, of those expressing a need to the alcohol treatment system over half (56%) that reported a mental health need said that their support came through primary care, with a fifth (20%) saying that it was through community or other mental health services. Very few (2%) reported being supported through talking therapy services.

Addressing alcohol in mental health hospitals

PHE’s guidance sets out two key principles for commissioning and providing better care for people with co-occurring mental health, and alcohol and drug use conditions.

- Everyone’s job. Commissioners and providers of mental health and alcohol and drug use services have a joint responsibility to meet the needs of individuals with co-occurring conditions by working together to reach shared solutions

- No wrong door. Providers in alcohol and drug, mental health and other services have an open door policy for individuals with co-occurring conditions, and make every contact count. Treatment for any of the co-occurring conditions is available through every contact point

For the last two and a half years staff in mental health hospitals have been asking their patients about their alcohol consumption and any harms they’ve experienced as a result. Where patients indicate that they’ve been drinking at levels that increase their risk of health harm they’ve been getting either brief advice on how to cut back, or if the problems are more severe a referral to more specialist advice and treatment.

The data returned by mental health hospitals shows that 16% of the inpatients who were screened were drinking at increasing or higher risk – a little lower than is the case in the general population. However, the rate of possible alcohol dependence was 8% compared to 1.4% in the general population.

Finding ways of addressing alcohol use with patients experiencing mental health problems is likely to benefit them both in the short and longer term, and it has been fantastic to see the system respond so positively to the challenge of doing so.

This case study shows how one trust has made this a part of normal clinical practice. Some of the things they found that worked well were:

- Integrating the screening (AUDIT)within the patient’s electronic record ensured that the risk is automatically calculated and, based on the score, the system prompts the health professional to undertake the appropriate type of intervention

- Ward managers could easily monitor the extent to which staff were screening patients

There are a range of resources available to health professionals to help address coexisting mental health and alcohol use conditions on PHE webpages.

These include the alcohol CLeaR approach to system improvement, an evidence-based approach that local alcohol partnerships can use to assess how effective their local system and services are at meeting need and preventing or reducing alcohol-related harm.

CLeaR promotes collaborative action and encourages all local stakeholders, including mental health and alcohol commissioners and providers, to develop a shared vision, then plan and work together to improve the outcomes achieved locally.

Local areas are strongly encouraged to use this approach to identify strengths and opportunities for development to progress this agenda.