Alcoholic liver disease has risen sharply in the last year.

Our report on alcohol consumption and harm during the COVID-19 pandemic shows an unprecedented increase in alcoholic liver disease deaths. In 2020, 5,608 alcoholic liver deaths were recorded in England, a rise of almost 21% compared to 2019. This is substantially above pre-COVID trends - between 2018 and 2019 the increase was under 3%.

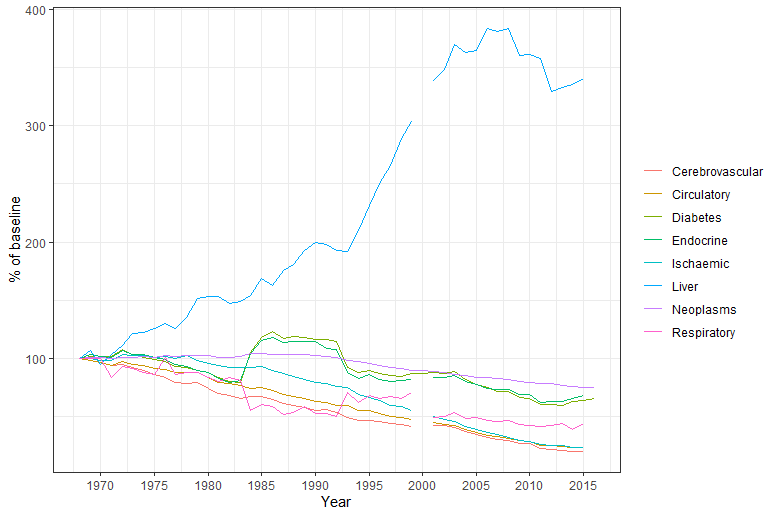

The spike in alcoholic liver deaths in 2020 occurred after a 43% increase in alcoholic liver deaths between 2001 and 2019. This is in stark contrast to other major diseases, like heart disease and cancer, for which deaths have either remained stable or decreased.

The above Data comes from https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/datasets/european-health-for-all-database/. and includes the last year of complete data across indicators (2015). Data are missing for the year 2000

Even before the pandemic, liver disease was the second biggest cause of premature mortality and lost working years of life in England and Wales behind ischaemic heart disease. And it is set to become the leading cause within 2 to 3 years. Liver disease is also now the biggest killer of 35 to 49-year-olds in the UK.

People in deprived groups in England are more likely to develop, be hospitalised by, and die from liver disease than the most affluent. In 2020, over half of all alcoholic liver disease admissions (57.7%) and deaths (56.5%) occurred in the most deprived 40% of the population.

Why are alcoholic liver deaths on the rise?

PHE’s report monitors changes in alcohol consumption during the pandemic and shines a light on the possible reasons for the sharp rise in alcoholic liver deaths. Based on analysis of sales data in the off-trade and surveys, it identifies an increase in alcohol purchasing, consumption and higher risk drinking (35+ units per week for women and 50+ units per week for men) since the pandemic started. This rise has been driven by those who were already drinking heavily before the pandemic.

Although alcohol-related cirrhosis may take over a decade to develop, people whose livers are already badly damaged can die when they suddenly increase their consumption. Because of this, liver mortality is a rapid indicator of changes in alcohol consumption among heavier drinkers.

How can we improve liver care?

Liver disease is a silent killer. It’s primarily caused by alcohol use and obesity and most people with the condition don’t know they have it until the disease is at an advanced stage. Research shows that people with advanced liver disease admitted to hospital in emergency are 7 to 8 times more likely to die than those admitted for stroke or heart attack.

But the liver is an incredible organ. Stopping drinking alcohol, or reducing intake to low-risk levels, can halt or even reverse damage to the liver. Once people stop drinking, their long-term survival improves dramatically. However, around one third of deaths occur before patients are aware of the risk and have the opportunity to stop drinking.

If more professionals routinely asked about alcohol consumption and referred people drinking at higher risk levels to have a liver investigation, many premature deaths might be avoided.

A diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease can motivate people to change their behaviour. One study reported that around 40% of cirrhosis patients stopped drinking after a first liver admission. In a community pilot, 65% of harmful and dependent drinkers reduced their drinking after learning they were developing liver fibrosis.

Early diagnosis

Providing an early liver disease diagnosis offers an opportunity for intervention. It allows people to access appropriate medical services that are effective for liver disease. Dependent drinkers with liver disease can get support from alcohol treatment services to help them stop drinking.

NICE clinical guidance on cirrhosis recommends thresholds for referral for liver investigation and identifies the specific tests that are able to stage fibrosis and cirrhosis. Standard liver function tests can’t accurately identify early stage liver damage.

Local public health and NHS commissioners should make sure that their liver treatment pathway offers the best opportunity to identify fibrosis and cirrhosis among higher risk drinkers in the early stages. They should also ensure that appropriate support is available for people to change their drinking behaviour and alter the course of the disease.

Individual-level interventions such as earlier identification and treatment are important components to reducing alcoholic liver disease.

However, population-level interventions are highly effective and cost-effective in lowering alcohol consumption and related harm by reducing its affordability, reducing availability, and restricting marketing exposure. So, the most effective response to alcoholic liver disease is a mixture of individual to population-level measures.

Interested in reading more about public health? subscribe to our blog here.