Within the UK Health Security Agency lies a scientific treasure trove, known as the Culture Collections. Its 4 repositories house thousands of meticulously preserved microorganisms, with some specimens dating back to World War 1 and the late 19th Century. At their heart is the National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC), which was established in 1920, making it one of the oldest collections of its kind in the world and the oldest constituent part of the UKHSA.

Far from being museum pieces, the irreplaceable scientific resources held within this collection have proven instrumental in tackling the most pressing public health challenges of the past 100 years. From identifying emerging pathogens to tackling antimicrobial resistance, read on to find out how these century-old samples are helping us to safeguard health today and to strengthen our defences against future threats.

Frozen in time

Why are these strains useful to scientists, even after 100 years?

The stories behind NCTC 86 Escherichia coli and NCTC 6571 Staphylococcus aureus, just two of the many thousands of bacterial strains that can be found within the collection, illustrate how microbial strains isolated decades ago can still be used today for a multiplicity of applications in science and industry.

E. coli – the NCTC 86 story

Inside the intestines and colons of every human lives a bacterial species called Escherichia coli, or E. coli for short.

While many people associate it with food poisoning, most strains of E. coli are actually harmless to humans. The bacterium takes its name from Theodor Escherich, a Bavarian paediatrician who first isolated it in 1885. The name combines Escherichia (after its discoverer) with coli (meaning ‘‘of the ’,colon’, indicating where it naturally resides). Escherich published his discovery in a scientific monograph the following year.

The strain was maintained in Escherich’s laboratory throughout his scientific career. Then, from 1900 onwards, it was distributed among several UK institutions, including the Pathological Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, the Royal Commission on Sewage Disposal and the Lister Institute of Preventative Medicine – before being received by the NCTC collection in 1920.

Now operated by the UK Health Security Agency, NCTC has maintained Escherich’s original strain throughout the 20th and early 21st Century, where it still exists 140 years after its original isolation, under the identifier ’NCTC 86’.

But why do scientists keep bacteria in collections like the NCTC? And given that Escherichia coli can be found in the intestines of numerous mammals, not just humans, what makes a specific strain of E. coli worth keeping around?

The many lives of a microbe

- A laboratory helper

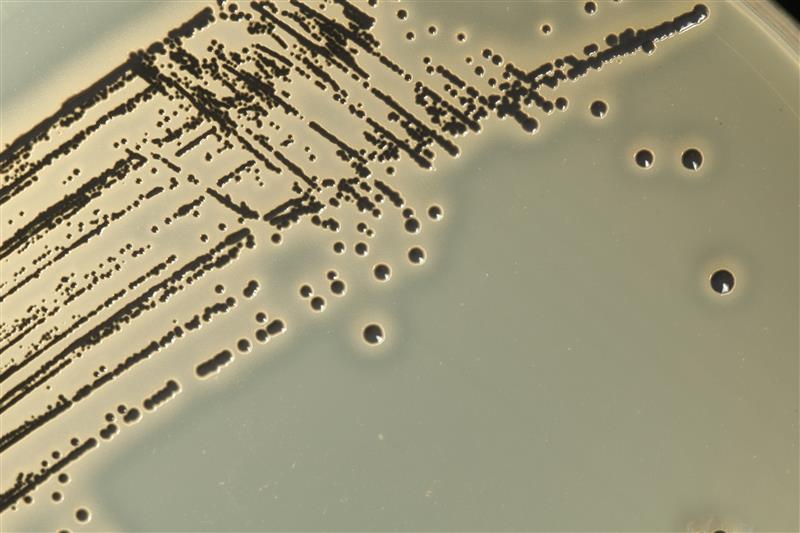

Scientists can use it as a quality control strain - essentially a ‘known quantity’ that helps ensure their tests are working correctly. It also played a crucial role in the development of MacConkey agar, a growth medium used in labs worldwide to tell the difference between E. coli (which is often harmless) and Salmonella (which can cause serious food poisoning). Early in the 20th Century it was also used as a disinfectant test strain, helping to ensure that industrial disinfectants and household cleaning products worked effectively.

- A window to human health

Escherich first described this bacterium while investigating how gut bacteria affect human health. By preserving his original strain, we've kept a valuable reference point for modern research. Today, scientists study how different strains of E. coli in our intestines might influence our health in what are called ’microbiome studies’.

- A digital pioneer

In the modern era of whole genome sequencing, NCTC 86 has found yet another new purpose: it was one of about 3,000 bacterial strains from our collection to have its complete genetic code mapped in a project known as NCTC3000. Its genetic blueprint is now freely available online for researchers to study and examine – what was once a physical archive of microbes is now transforming into a digital genetic library as well.

Currently, a PhD student working with NCTC and the University of East Anglia is comparing the genetic makeup of NCTC 86 with 280 other E. coli strains collected over a century, helping us to understand how this important bacterium has evolved over time.

S. aureus – the NCTC 6571 story

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)is a bacterium that can harmlessly inhabit the human body, with as many as 30% of humans being long-term carriers in their skin, nostrils or reproductive tract. However, it can also cause serious illness including soft tissue infection, toxic shock syndrome and sepsis.

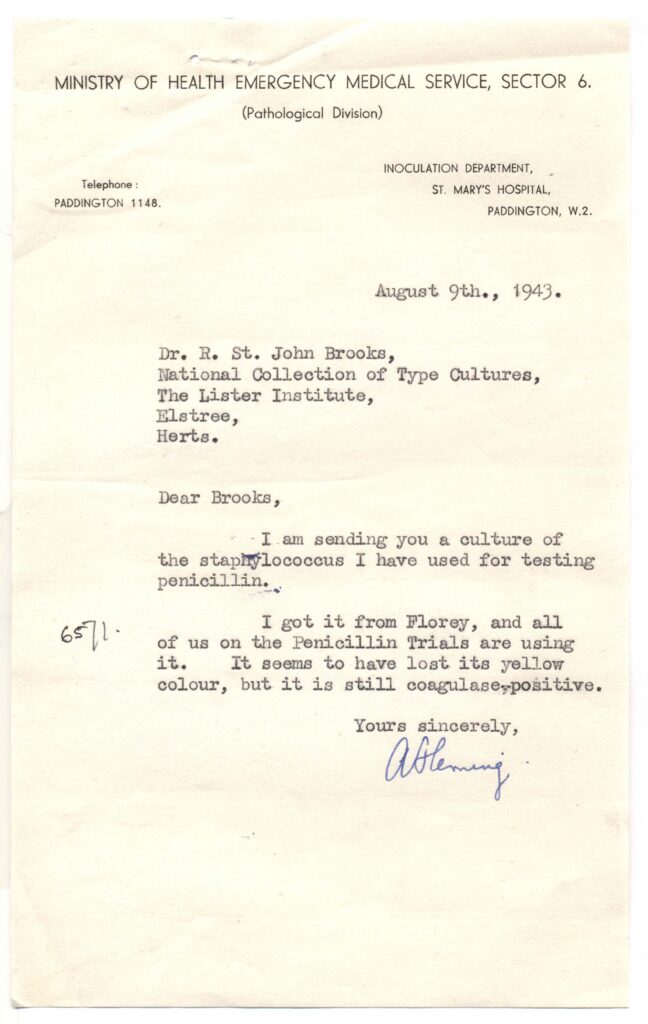

In 1943, Sir Alexander Fleming - whose discovery of penicillin revolutionised medicine - deposited a S. aureus strain into the NCTC collection. This strain, affectionately known as ’Oxford Staph’ or ‘the Oxford Staphylococcus’, had been used in the penicillin trials at Oxford University. Eight decades later, this same historic microbe (under the identifier NCTC 6571) continues to play a crucial role in research.

Another notable early adopter of NCTC 6571 was English biologist and biochemist Norman Heatley, also a member of the Oxford team that developed penicillin. Heatley used it to measure how strong each batch of the medicine was, which was crucial at a time when penicillin was new and difficult to produce consistently.

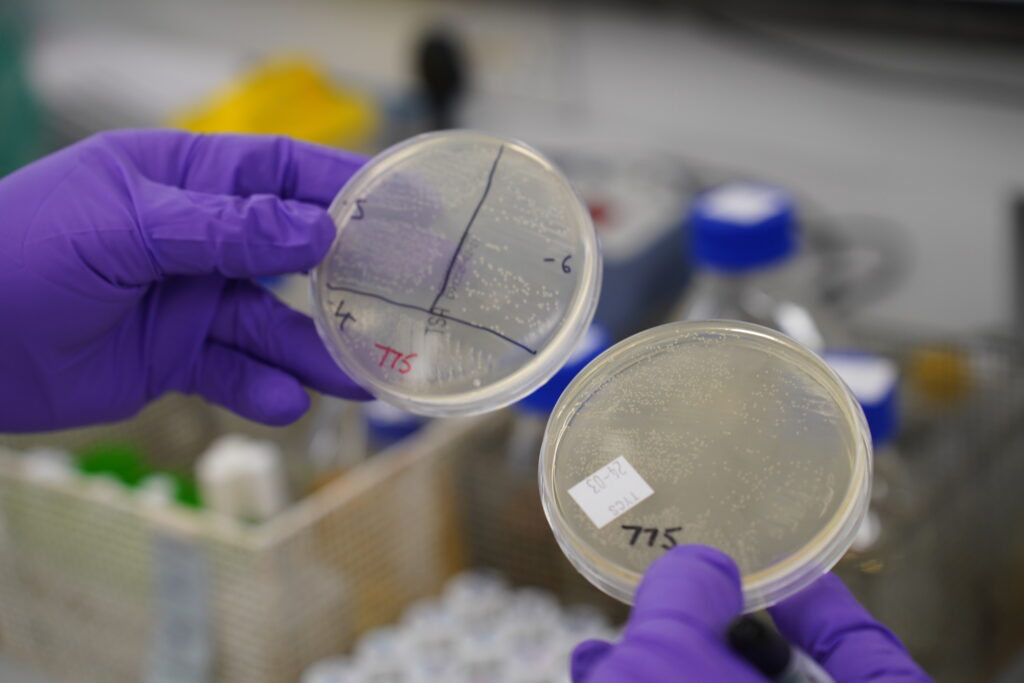

The use of NCTC 6571 in this context continued long after World War 2; since 1949, the NCTC has produced and supplied more than 8,000 samples of this same bacteria to researchers worldwide.

What made NCTC 6571 so special that it was used for this purpose? Interestingly, no one knows exactly why this particular strain was adopted. In his letter to the NCTC (pictured above), Fleming simply wrote, ‘I am sending you a culture of the staphylococcus I have used for testing penicillin. I got it from [Howard] Florey, and all of us on the Penicillin Trials are using it.’

The origins of NCTC 6571 and why it was selected otherwise appear lost to time.

New discoveries in old samples

With genome sequences becoming more readily available, we can now read the complete genetic code of bacteria, providing additional insights into samples that have been preserved for decades.

For example, NCTC scientists recently sequenced 133 strains of S. aureus as part of the NCTC3000 project, including Fleming's NCTC 6571. The scientists were interested in genes that make some of these strains harmful to humans, known as enterotoxin genes.

While examining the genetic data, the researchers discovered 2 previously unknown enterotoxin genes. Surprisingly, at least 1 of these genes still exists in strains circulating today. This shows how preserved bacteria from the past can help us understand present-day health threats.

Furthermore, a second NCTC/UEA PhD student is currently conducting a significantly expanded study analysing thousands of globally isolated S. aureus strains, using data science and machine learning techniques to gain insights into enterotoxin gene evolution.

Nature's living tools

Unlocking the potential of microbes isn’t an activity confined to Oxford in the 1940s. Microbes are valuable resources driving scientific innovation, and they perform remarkable functions that scientists continue to harness for developing new technologies.

For example, some microbes can:

- ‘eat’ man-made plastics (Ideonella sakaiensis NCTC 14201)

- produce natural antibiotics (Streptomyces griseus NCTC 13033)

- demonstrate how rapidly some bacteria can evolve antibiotic resistance (AMR) (Escherichia coli NCTC 13846)

- serve as models for studying how and why some bacteria cause human disease (Streptococcus pneumoniae NCTC 14077).

Supporting scientific progress

The NCTC collection also plays a crucial role in:

Testing new antimicrobials

Researchers are using our strains to evaluate novel antimicrobials (Neisseria gonorrhoeae NCTC 14208) and evaluate new diagnostic techniques (Staphylococcus aureus NCTC 14245).

Expanding Scientific Knowledge

When scientists discover bacteria previously unknown to science, they can compare them to reference strains from the collection like Campylobacter jejuni (NCTC 11168) and Campylobacter lanienae etc (NCTC 13004).

Practical Applications

Microbes from the collection are used to evaluate everyday infection prevention practices, such as the difference between handwashing with warm water versus cold water (Escherichia coli NCTC 10538) and in the surveillance of antimicrobial resistance (Klebsiella pneumoniae NCTC 13368).

Others may be used in years to come in ways in which we can only imagine today.

The future

The foresight of those who preserved these microscopic organisms throughout the past century has given us an invaluable resource, and as modern techniques like whole genome sequencing become more advanced and accessible, the full value of their legacy is only beginning to be realised.