Syndromic surveillance is an innovative way of collecting and analysing health surveillance data and is becoming an increasingly popular way of monitoring public health across the world. Syndromic surveillance complements existing programmes, which are usually based upon traditional laboratory reporting, providing additional information about infectious disease outbreaks or other public health incidents that can affect the health of the population.

In this blog we’ll unravel what syndromic surveillance is and why we undertake this form of surveillance.

What is syndromic surveillance?

Syndromic surveillance is a tool we use to collect information about the general public’s health and to see, in real-time, whether there are any diseases which are following an unusual trend, like a sudden increase at an unexpected time of year. Syndromic surveillance primarily measures the reporting of symptoms caused by anything from flu to norovirus. It’s not simply bugs we look at, either. This surveillance can also measure things like hayfever and eye problems caused by summer pollens. Using the symptoms associated with different illnesses provides a way of detecting problems early and allows us to follow the size, spread, and tempo of the outbreaks and to monitor seasonal disease trends in general. Collected from emergency departments (A&Es), general practices and other types of first line patient care services, syndromic surveillance is an excellent way of taking a rough picture of the nation’s general public health at any one time.

In simple terms this type of surveillance collects anonymous information from patients at their first point of contact with medical care (for example, with their GP) which scientists can then look at to monitor trends over time. This is not to say that we only look at syndromic surveillance data: this information is always used alongside traditional laboratory data.

Why do we undertake syndromic surveillance?

In general there are three underlying purposes that syndromic surveillance aims to achieve:

Providing early warning of seasonal illness

One of the most important features of syndromic surveillance is the ability to provide early warning of seasonal illnesses compared to laboratory surveillance, which takes a lot more time to get data back from. We are always looking for ways to provide our public health teams with as much early warning of infections as possible and to improve our response to seasonal outbreaks.

Providing ‘situational awareness’ during a seasonal outbreak or public health incident

During any seasonal outbreak of disease or public health incident, for example an outbreak of norovirus during a mass gathering, those who are coordinating the public health response need to know what is happening. The questions they often ask are:

- which areas of the country are being affected by the outbreak/incident?

- are particular age groups being affected?

- are there signs that the symptoms people have are getting more severe?

- when has the outbreak/incident peaked (that is, when will things return to normal)?

Syndromic surveillance can provide some answers that help to address these questions.

Providing reassurance about the lack of impact of an incident or mass gathering

During a public health incident it is important to report both when there are obvious health impacts and when there are not. Syndromic surveillance is able to provide some of this reassurance because the systems we use look at the general population surrounding an incident rather than just focusing on those who have been directly affected.

Where have we used syndromic surveillance and was it useful?

Some examples of times we’ve used syndromic surveillance are:

1. 2009 influenza pandemic

During the 2009 influenza pandemic, syndromic surveillance systems were able to provide situational awareness during the pandemic, informing public health officials where the impact of the pandemic was at its worst, and which age groups appeared to be affected.

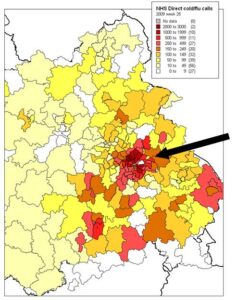

The map below is taken from one of our surveillance reports and illustrates the intensity of ‘flu activity across the West Midlands as measured through calls to NHS Direct. The arrow illustrates the location of Birmingham, highlighting the focus of pandemic ‘flu infections in the West Midlands during the early stages of the pandemic.

2. Volcanic ash cloud, Iceland, 2010

During the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano a large ash cloud covered significant parts of Europe. There was concern about whether the ash cloud could cause health problems, especially to individuals with underlying chronic respiratory problems however we were able to show that this was not the case. This information was used, alongside other data sources (e.g. environmental monitoring) to provide reassurance to health care professionals and the general public of the very low risk to health of the ash cloud.

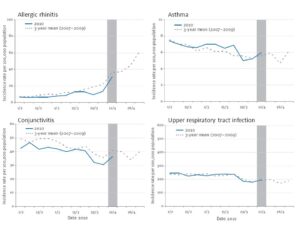

The graphs below are taken from our report on the incident. Each panel shows the recorded levels (blue line) against the expected levels (grey dashes) for syndromic indicators during the period that the ash cloud covered the UK (grey bars).

3. London 2012 Olympic Games

During the 2012 Games, we used our syndromic surveillance systems to monitor the health of the population, especially within London during ‘Games Time’. The large influx of foreign visitors and the high profile nature of the event meant that there were certain public health concerns around the event. Our systems provided vital information which was used in parallel with other national surveillance systems to provide reassurance that there were no major problems in those areas located near Olympic venues.

4. Flooding, 2014

We are currently involved in the national public health response to the 2014 floods across England. As part of a surveillance group (including laboratory reporting), syndromic surveillance is being used to monitor the health of those areas particularly affected by the flooding. Although infection problems arising from floods in this country are rare, we’ve been monitoring levels of gastroenteritis, including diarrhoea and vomiting, to assess whether people in those areas affected by the floods have been reporting higher rates of illness. This information has been important in providing reassurance to local and national public health teams, and to local and national government, that we are not seeing outbreaks of infectious diseases associated with flooding.

What’s next?

We are continually exploring future sources of health data to use for syndromic surveillance including social media, ambulance data and over the counter drug sales. Each will be assessed to understand what advantages, if any, they provide over our existing systems. We are also working with colleagues overseas to further explore the usefulness of syndromic surveillance in public health across the world.

Further information about our syndromic surveillance can be found here.

2 comments

Comment by Bren posted on

Hello Alex,

A really interesting blog and one that reflects the evidence based decisions at Public Heath England.

I was particularly interested in the syndromic surveillance and the 2014 flooding, and whilst physical signs were cited, I wondered if syndromic surveillance is used on the psychological impact such as depression.?

Thanks and a very informative blog.

Bren.

Comment by Alex Elliot posted on

Hello Bren

Many thanks for your comments. Currently, our syndromic surveillance systems are not able to monitor the mental health impact of floods. However, we have recognised that this is an area that we need to develop and we are currently undertaking a project to explore whether we can use syndromic surveillance to monitor psychological health issues (for example depression, anxiety and stress) during floods, and other public health incidents.

Thanks again and please let me know if there is anything else that I can help with.

Alex