Tuberculosis (TB) is a vital public health problem facing England. Rates have stabilised over the past seven years, but the incidence of TB in England remains high compared to most other Western European countries.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a vital public health problem facing England. Rates have stabilised over the past seven years, but the incidence of TB in England remains high compared to most other Western European countries.

TB is transmitted from person to person by the inhalation of infectious droplets, coughed by patients with TB. It will infect about half of their close contacts such as family or household members. Once infected, only a minority will go on to develop clinical disease and this usually occurs within 2-5 years but occasionally it can occur many years later. This long and unpredictable chain of transmission can be interrupted by rapid diagnosis and treatment of cases and our experience demonstrates that rigorous TB control programmes can lead to major reductions in the rate of TB.

Contact tracing from information volunteered by the patient is insufficient to find all linked cases. The main tool for examining the relatedness of cases is called strain typing, where molecular methods are used to examine the relatedness between TB bacteria from different patients to identify transmission. The National Strain Typing Service, established in 2010, involves prospectively typing all new TB isolates. Clusters of patients with indistinguishable typing profiles which fulfil certain criteria are then investigated to try to identify epidemiological links and transmission settings to inform a public health response.

Recently published work on the investigation of TB clusters in Canada and England has shown that whole genome sequencing offers superior discrimination to the current 24 locus MIRU-VNTR method. PHE was a major partner in the England work and PHE’s Public Health Laboratory Birmingham provided the TB specimens and epidemiological linkage with Oxford University.

In addition the Birmingham lab worked together with Oxford University and two other labs in England and international partners (from Germany, Ireland, France and Canada) to establish the feasibility of applying whole genome sequencing rapidly and consistently in multiple laboratories plus sharing the analysis and interpretation.

The genome sequence provides information to identify the mycobacterial species and gives a prediction of the phenotypic drug resistance as well as comparing with known strains to determine their relatedness. Further research work is also taking place to refine the sensitivity and specificity of drug resistance predictions.

This second project developed a more rapid method of extracting DNA from TB and sequencing locally, as soon as the culture had grown in each of the eight laboratories the raw information from the sequencing was assembled and analysed and a collaborative approach ensured that all eight centres were able to implement the techniques and share results.

In December 2012 the Prime Minister announced that the UK would sequence 100,000 human genomes to develop capacity and capability in genetic science. PHE has been asked by the Department of Health to lead developments in pathogen sequencing to link into the work on human genomes. PHE has decided that a pilot to use the sequencing of TB in real time should be part of this work.

We are now moving into an exciting phase of the work with a PHE led pilot, based initially in Birmingham. The pilot will sequence all cultured isolates of mycobacteria as rapidly as possible, in parallel with the existing reference service for identification, drug resistance testing and strain typing.

In the early stages, sequencing will be carried out on all strains identified as being Mycobacterium tuberculosis. All TB isolates will also be examined using MIRU-VNTR and the pilot will work closely with NHS labs to develop an accredited sequencing service. The pilot will run for the next year and lessons will be learnt about how to set up the service and how to run it. Speed, accuracy and reproducibility against the current diagnostic service will be considered in an analysis of cost effectiveness.

The work will help us examine how data from the sequencing service is linked to routine TB surveillance and how the benefit that greater depth of knowledge, which sequencing brings, will be shared.

All of this work shows the need for development and training for the scientists in laboratories, epidemiologists, clinicians and public health doctors so that together as a team we can learn how to achieve better control of TB and contribute to a reduction in TB in England whilst also making an important pathogen based contribution to the 100,000 Genome Project.

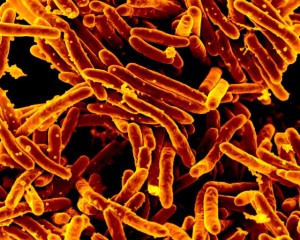

Featured image Mycobacterium tuberculosis Bacteria, the Cause of TB by NIAID. Used under Creative Commons.

1 comment

Comment by Bren posted on

Hello Christine,

Thank you, as before, for a really interesting and informative blog and your ability to put high level science in lay understanding is really great.,

I noted from your blog the transfer ability of the infection to the clinical disease and just wondered if this was widely known in the general public.?

I also noted the great connectivity with many partners in this work, locally and nationally, all with a very purpose. We must not overlook the leadership that makes this happen and so good on you and the team for this.

The pilot work will be another clear demonstration of the value of Public Health England, and partners, in the control and reduction of Tuberculosis in England. The results being shasred wider will hopefully support this too.

My only thought would be how to share the information outside of scientific circles and for the wider public, in ongoing marketing and campaign material.

Thank you for sharing this great blog Christine and all good wishes,to you and all the team(s).

Bren.