Elisabetta Groppelli lead on PHE’s Ebola response on the ground in Sierra Leone. She was deployed to Sierra Leone to support Public Health England’s response efforts in fighting Ebola. During 2015 there was significant progress in the Ebola response.

Yet, while the successes and improvements made to public health infrastructure in West Africa are important to celebrate, the work continues to end the largest Ebola outbreak in history. In this blog she gives an insight into her time in West Africa and answers some questions on her experiences and the challenges she faced.

When did you first travel to Sierra Leone?

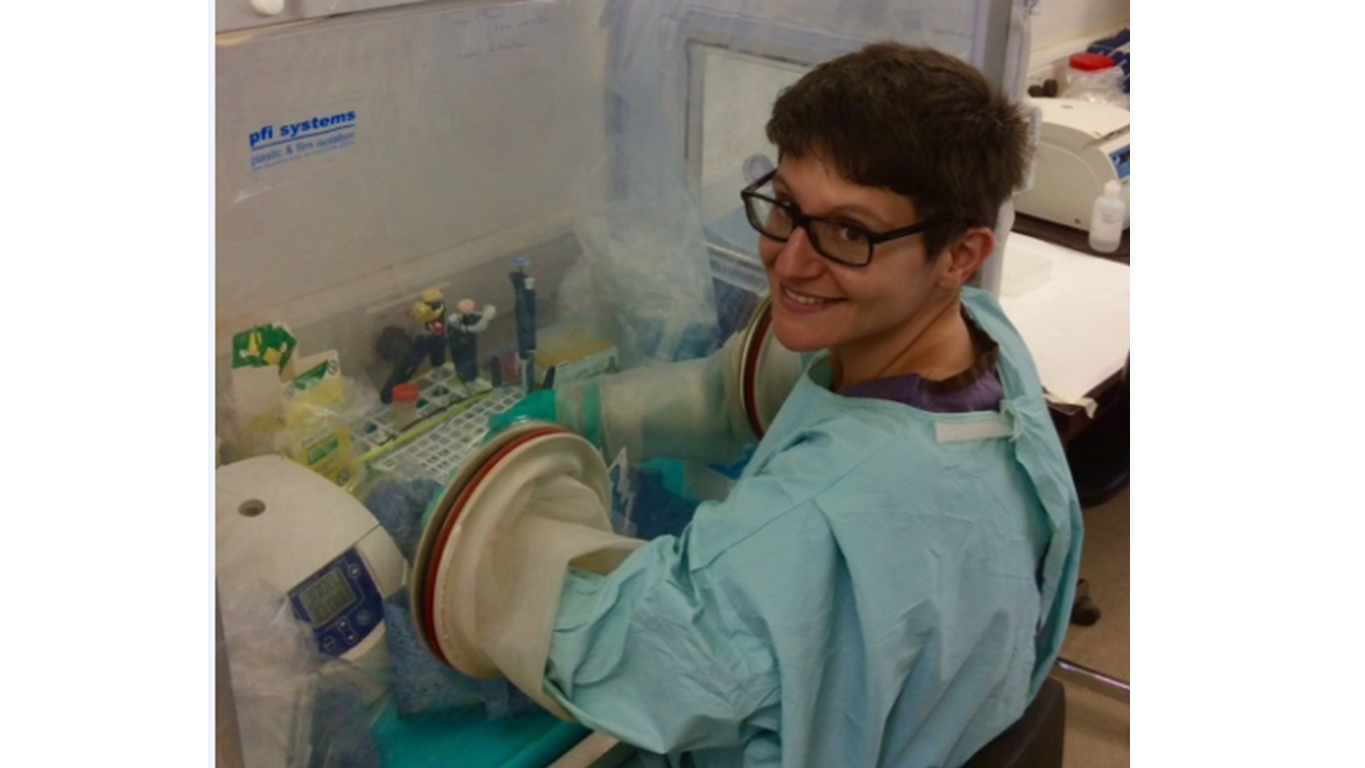

My first time in Sierra Leone was in February 2015. I joined the PHE effort as team leader at the PHE Port Loko laboratory.

The lab provided Ebola testing for patients admitted to the Ebola Treatment Centres in the Port Loko and Kambia districts. These two districts were hit hard by Ebola and my time in the lab was very busy processing as many samples as I could a day. My role as team leader involved both managing the lab, but also being the link between the lab and the other organisations involved in the outbreak response.

After a short break, I returned to Sierra Leone in July 2015 but this time as PHE in-country lead. I have found that the role has been very dynamic as the situation on the ground is ever changing.

Initially, I was involved in coordinating the effort of the three PHE laboratories in Sierra Leone. My role now involves transitioning the PHE Ebola labs to permanent structures integrated in the national health care system. The aim is to support Sierra Leone to strengthen basic diagnostics services and to increase its resilience to outbreaks.

My experience in the field showed me the crucial part that diagnostics play in the context of an outbreak. It was amazing and humbling to understand the pivotal role of the diagnostic lab and how it shapes the outbreak response in the field. I felt immensely proud when Ebola response teams said that the PHE labs were a game changer.

As in-country lead, I am involved in working in partnership with the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and many other international stakeholders to help shape Sierra Leone’s future regarding strengthening the health care system and outbreak response. How we react to new Ebola cases or the next outbreak will show the level of difference we are making now.

What time during the Ebola response was most-challenging for you?

The most challenging time for me was performing the mental switch from a research lab to diagnostic lab in the context of an outbreak. As a research scientist, I see results as data that needs to be analysed and that will contribute to answering my scientific question.

So, in a way, all data has a generally positive meaning. However, in diagnostics and especially in the Ebola outbreak diagnostics, the results have such a profound and heavy human meaning. I found myself experiencing the ‘diagnostics roller-coaster’, in which a negative result would make me sigh of relief, but I would be hit hard by a positive result and the thoughts of its consequences for the individual, the family and the country. However, regardless of the negative or positive results, the certainty that we were addressing and stopping the outbreak kept me grounded and focused.

What is your best memory from your involvement in the Ebola response?

Personally, the best memory was when my team made me a mother’s day card. The team had worked closely and hard for weeks and had effortlessly developed a strong bond, like a family. In this lab family, I was the mom! The card (a beautiful picture of the family with nice messages) was a tangible recognition of how well we worked together despite the challenging and stressful environment of the Ebola outbreak. I keep a picture of the card in my iPhone.

Do you feel you have made a difference?

I like to think that I did. However, the reality is that the difference was made by the UK, PHE and the corresponding decision makers who have organised a response that had a huge impact in the outbreak and its outcome. Naturally, this was then turned into reality and results by the many individuals who volunteered to go to Sierra Leone, which includes me. As an individual, I certainly worked and continue to do so to the best of my abilities to contribute to the bigger effort.

What has been the highlight of the Ebola response for you?

There have been many highlights during the response. Witnessing and being part of a global effort to fight an outbreak has been a fantastic experience. For me as a virologist, the outbreak has been a fascinating time for science. New and classical virological questions have come up and it is a privilege to be involved in answering them.

What lessons were learned from your time in West Africa?

A great and reassuring lesson has been that the UK and organisations like PHE, NHS and academia can step up at short notice and contribute to global health security. However, it’s become apparent that the baseline level of readiness was sub-optimal and this needs to be promptly addressed.

From the laboratory and diagnostics point of view, it’s become apparent that absolute prioritisation of investment towards rich-country diseases is a very risky strategy at the global level. Research, pharmaceutical and government institutions need to steer the new directions of research and development in view of the challenges faced during the Ebola outbreak.

What’s the current situation in West Africa?

The Ebola epidemic is now in its final stage. However it is important that we still identify, prevent, and respond to outbreaks to prevent future epidemics of this magnitude. Hand washing buckets, chlorine, temperature checks and road blocks are still in place. Families and friends dealing with bereavement still need to deal with burial procedures that are shaped and dictated by Ebola and have had profound effect on important traditions.

Nevertheless, there is a generally feeling of positivity and optimism in Sierra Leone. Life is returning to pre-outbreak activities, which include buzzing, colourful and loud markets and busy and competitive football matches.

Are the PHE labs making a difference?

The labs have been described as a game-changer. Because the symptoms of Ebola are very generic (fever, diarrhoea and vomiting), especially as they are first manifested, they can be ascribed to other less life-threatening pathogens. The diagnostic test is the only way to categorically identify or exclude Ebola cases. This has therefore a huge impact in shaping the next steps of the case response and clinical management of the patient.

What challenges remain for the people in West Africa?

The outbreak has highlighted substantial challenges and gaps in both disease surveillance and response, but also in the general health care system. These gaps involve resource availability but, most importantly, technical and managerial expertise. How Sierra Leone/West Africa with the help of partners will address this and make long-term sustainable changes will be crucial for both Sierra Leone/West Africa and, as we’ve learnt, the rest of the world.

The Ebola outbreak has also highlighted that western medicine, science and resources, although necessary, are powerless without engagement at a cultural and human level. The challenge for both West Africa and the Western world will be to collaborate and integrate visions and approaches in order to have the best outcome at the general population level both locally and globally.

What are the next steps for managing Ebola in country?

On the ground we are experiencing a period of continued and heightened surveillance. Health care workers are encouraged to collect samples and send them to the laboratories for Ebola testing should they come across a potential case. Additionally, Ebola testing is performed on all deceased to rule out Ebola as cause of death.

It is expected that the region (i.e. Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea) will experience sporadic Ebola cases in the near future. This is due to the nature of the infection and is therefore difficult to predict. So it is crucial that both national and international organisations remain vigilant and ready to act. At the same time, a large effort is ongoing to transfer surveillance and outbreak response to the local authorities and generate a robust national system. This would apply to Ebola but also to all other pathogens of outbreak potential.