We need to find people with advanced hepatitis C virus related liver disease and provide treatment in order to prevent them dying prematurely from this chronic infection or needing liver transplants or progressing to liver cancer.

This is because in our recent publication in the Journal of Viral Hepatitis we found that new direct acting antiviral drugs have the potential to transform the hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment landscape.

For many people living with hepatitis C, we now have a fast and effective cure, without many of the complications associated with previous treatments. However, as with everything with hepatitis C, the way forward is complex and requires careful thinking.

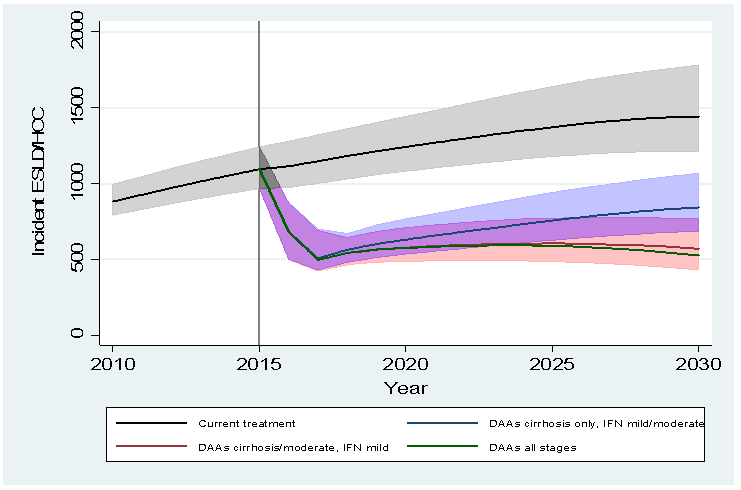

Our recently published modelling study confirms that by treating 3,500 people with cirrhosis each year, new cases of HCV-related end-stage liver disease and cancer could be reduced from 1100 cases per year in 2015 to about 630 in 2020.

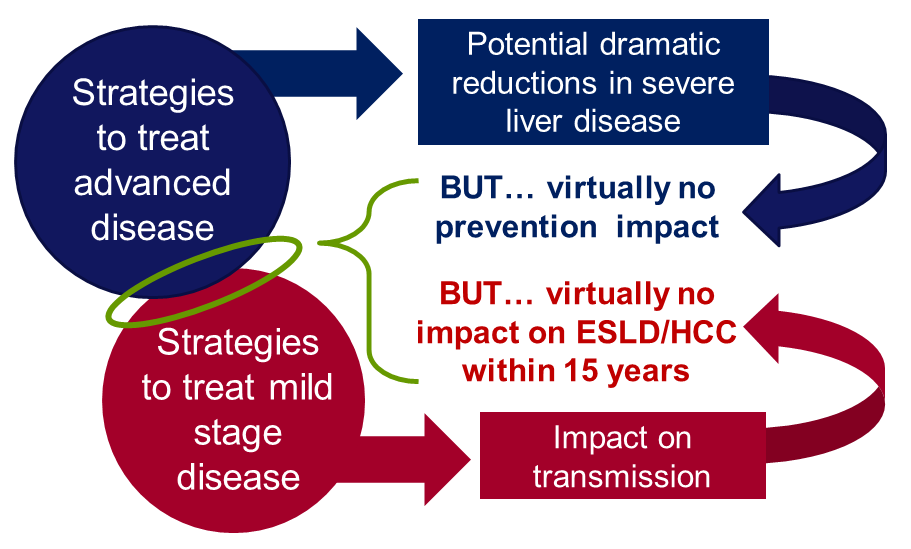

That’s a 50% reduction in hep C related end stage liver disease and liver cancer by the next Olympics. However, our work shows that these reductions will not be sustained beyond 2020 without these therapies being available to those with moderate disease (people who don’t yet have severe disease and cancer).

In addition, only treating patients with severe liver disease will have minimal impact on preventing new cases of hepatitis C.

There are also those who may have acquired their infections many years earlier, for example following a brief period of injecting drug use or via blood transfusion before the introduction of screening of the blood supply in 1991.

These people may be unaware of their infections because they have only mild or no symptoms; if we don’t do more to identify these people, they are likely to remain unaware of their risk until they present with advanced disease.

If we are serious about tackling hepatitis C, it’s not enough to treat the liver damage caused by the virus, but we also need to prevent infection in the first place.

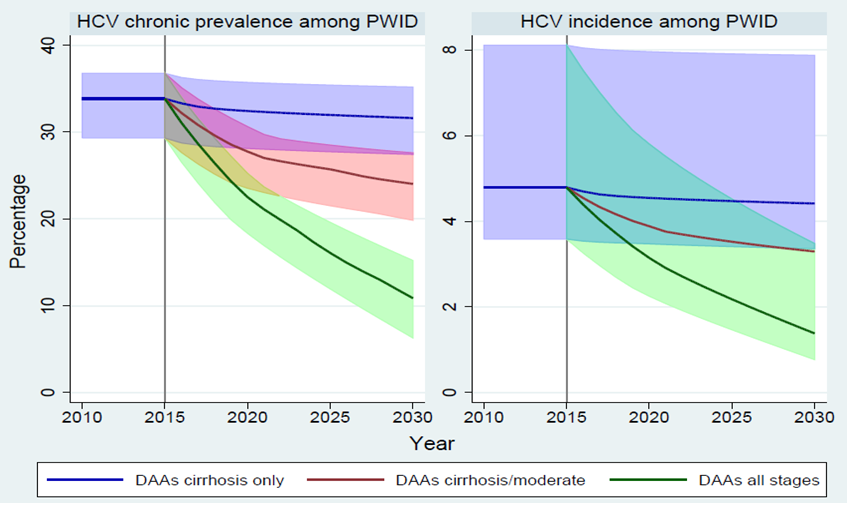

Transmission in England occurs mainly among people who share drug injecting equipment. Our study shows that if we can diagnose and deliver HCV treatments to those people with mild disease who are injecting drugs and transmitting the virus, and combine this with other harm-reduction activities like needle and syringe programs and oral substitution therapy, we could potentially eliminate hepatitis C as a serious public health concern in England.

However, once diagnosed, the challenges of ensuring that these groups access treatment are much greater, yet because the new drugs are easier to administer, have shorter courses and improved safety profiles, they are easier to roll out into community settings that are more accessible to these groups.

I don’t believe there are ‘hard to reach’ groups, only services or treatments that are difficult to access.

Providing treatment to people with severe liver disease and saving lives is a great and essential first step, but we have to view this as just one part of an overall strategy which prevents severe disease developing and reduces the number of people becoming infected in the first place