People are quite rightly increasingly concerned about antibiotic resistant bacteria and the search for new diagnostic tools and medicines, but we must never lose focus on simply preventing these infections from occurring in the first place.

Anyone with an interest in healthcare will be well aware of the long-term fight against MRSA and Clostridium difficile and the hard work that’s gone into reducing rates of those infections.

But we face equally challenging times with a new battle against Escherichia coli bacteraemia (E. coli), on our hospital wards and in the community.

The statistics tell their own story; we saw over 38,000 E.coli cases reported by NHS Trusts in 2015/16 – that’s an 18% increase from 2012/13.

And these infections led to a significant number of deaths, particularly in the very young or old, in people who have a respiratory infection or unknown infection as the underlying cause, those who acquire the infection in hospital and worryingly, we’re seeing deaths linked to antibiotic-resistant E. coli.

We also see more cephalosporin resistant E.coli blood stream infections (approximately 4000) than MRSA blood stream infections (approximately 800) a year and they are arguably more difficult to treat than MRSA as there are fewer treatment options.

Acquiring a resistant E. coli bloodstream infection (sepsis) increases the risk of mortality by on average 30% compared to bloodstream infection caused by an E. coli susceptible to key antibiotics used for treatment.

Our data also show that urinary tract infections are the most common cause of E. coli bacteraemias and lead to the highest number of deaths due to the prevalence of these infections.

These statistics combined with a general push to reduce the burden of antibiotic resistant infections have led to a strong Government focus on reducing preventable E. coli bacteraemia (including setting a target of a 50% reduction of healthcare associated Gram-negative bloodstream infections by 2020).

Preventable E. coli bacteraemia

Health professionals in every setting are on the front line of this battle and must keep making a positive impact on infection prevention and control (IPC) every day.

Too often we see misconceptions about IPC - that it’s just about hand hygiene and cleaning – when it actually requires a much wider range of measures to succeed.

Effective IPC is about strong leadership, training and education, surveillance of infections, guidelines and procedures, optimising antimicrobial use, aseptic technique and safe clinical practice, clean and safe environments (including water and food safety), occupational health and vaccination, laboratory support and links to public health and health protection…the list goes on.

This is challenging work for professionals across the health and care system, but the reward for getting it right is saving lives.

Of course, every infection prevented reduces the need for and use of antibiotics, which in turn lessens the potential development of resistance.

We all have a role to play in this whether we work in health care or are members of the public.

IPC tends to only really hit the headlines when we’re discussing SARS, MERS-CoV or Ebola and there is the most heightened awareness of the need to prevent transmission.

But with the looming threat of a post-antibiotic world there’s a greater need than ever, to focus on our day-to-day work treating people in their homes and in hospitals.

Breaking the chain of infection

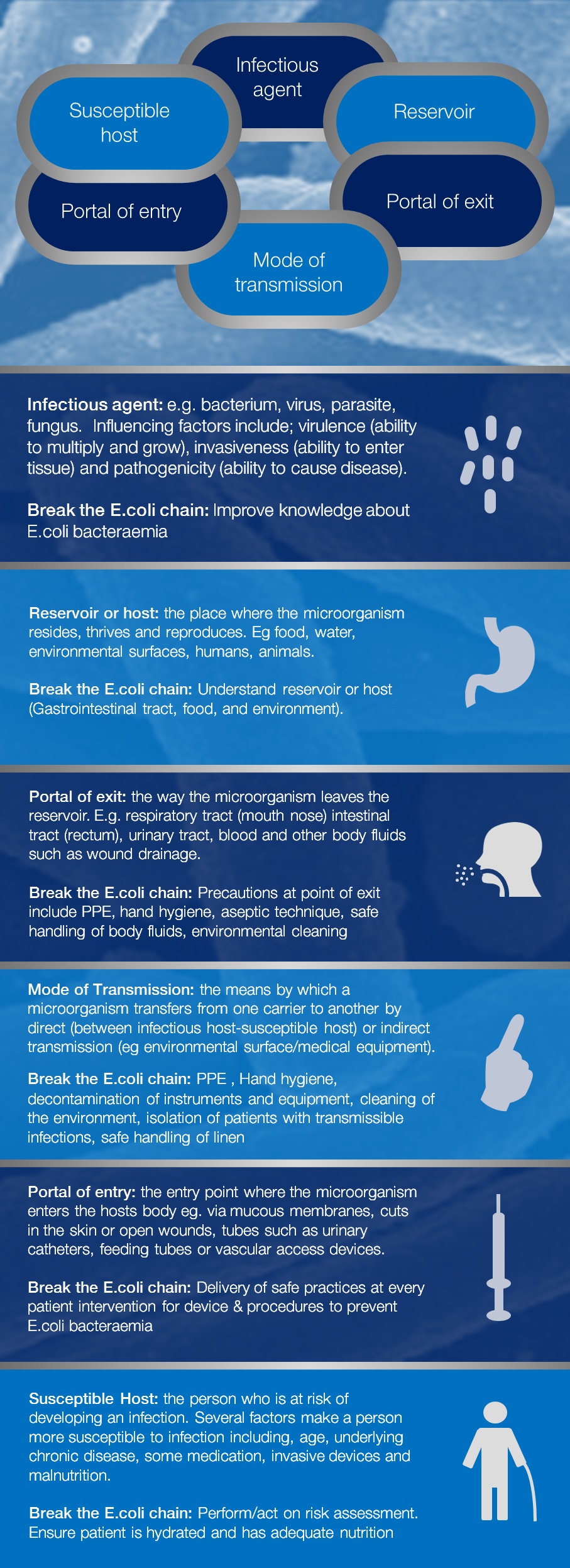

There are certain conditions that need to be met for a microorganism capable of causing infection to spread, involving the microorganism, hosts and environment.

There must be a portal of exit from one host e.g. microorganisms causing respiratory infections being spread in sputum expelled by coughs or sneezes.

This is transferred via a mode of transmission e.g. hands/droplets, and enters a new host through a portal of entry like the nose/mouth. These steps are called the chain of infection (see graphic below).

Each step represents a link in this chain and if all the links in the chain are present, an infection develops. If one or more links are broken, the infection will be prevented.

Health and social care workers play a vital role in breaking this chain - every day - during every single patient contact.

But how do we go about breaking the E. coli chain and preventing some of the thousands of cases we are seeing in the community and in hospitals?

With E.coli we want professionals to develop more knowledge about this microorganism (the infectious agent) and how it’s transmitted as well as the ‘reservoir’, which in the case of E. coli infections is often the gastrointestinal tract of humans, though of course could be food or the environment.

One focus should be on preventing contamination of the environment with gut organisms (portal of exit) with safe handling and disposal of body fluids including the management of diarrhoea, appropriate PPE, hand hygiene and aseptic technique for all dressings.

This work can prevent the bacteria spreading (mode of transmission) and break the chain at this stage.

I explained that E. coli and UTIs were a particular concern and so attention to preventing UTIs through good hydration in the community is important. When a UTI is present, correct diagnosis and using the right antibiotic is essential to prevent the UTI progressing to a bloodstream infection and clinical sepsis. The PHE guidance can assist making these decisions.

Also catheter insertion and care is absolutely paramount as another way of breaking the chain (portal of entry). Always question if the catheter is needed and consider other options. If essential, ensure aseptic technique is followed and the catheter is cared for and review whether it is needed every day.

And continuing with this example, risk-assessing your patient could break the chain (susceptible host). Are they more vulnerable because of age or health factors? Do they have a history of UTI? Are they dehydrated or malnourished?

These are just a handful of examples, and whilst the concept of the chain of infection is simple, the levels of bacterial infections we’re seeing show there’s still more we can and must do, whether as front line professionals, IPC experts, trainers, managers or system leaders.

I urge everyone to read the AMR handbook for more information, which collates national resources on antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial stewardship and infection prevention and control. The International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene have also produced a resource.

This week is International Infection Prevention Week (October 16-22).