Since new direct acting antiviral drugs have become available, the initial focus has understandably been on their role in averting severe hepatitis C-related liver disease and preventing the early death that can result from this.

In fact, our recently published hepatitis C report suggests that we may be making headway here, with better access to improved treatment leading to the first fall in deaths from this indication observed in a decade.

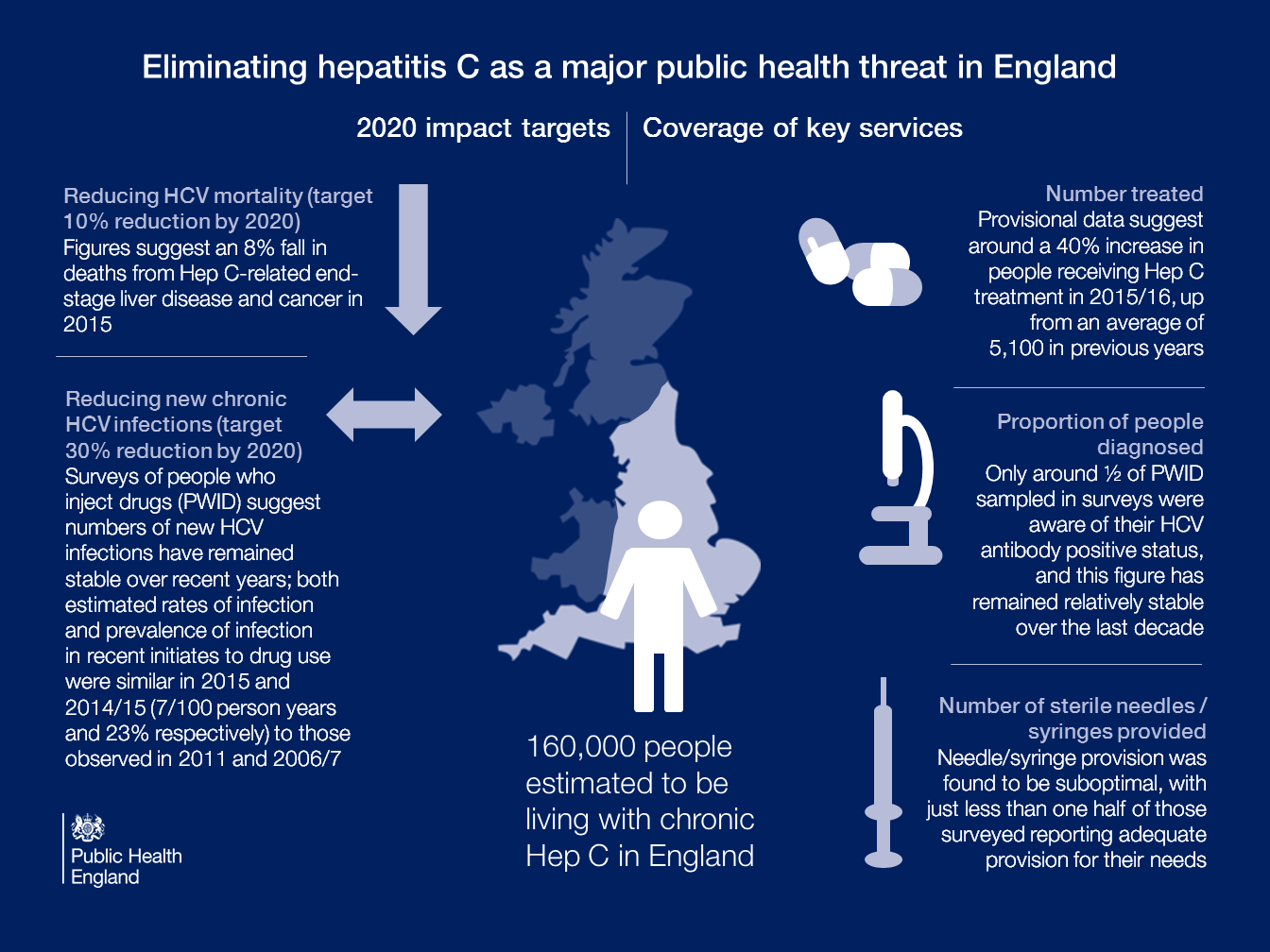

Having achieved an 8% fall in deaths in 2015, we seem to be on the right road to meet the new World Health Organisation (WHO) target to reduce hepatitis C mortality by 10% by 2020.

However, in a relatively short time, we will have treated those who are diagnosed and in care, and a key limiting factor will be our ability to find the undiagnosed.

Hepatitis C deaths will not continue to fall if we fail to find the undiagnosed and refer them in a timely way for life-saving treatment.

Meeting our WHO target of a 65% reduction in hepatitis C mortality by 2030 will be partially dependent on our ability to achieve this. If we are to meet the WHO target of 90% of people with chronic infection being diagnosed and aware of their infection by 2030, more work needs to be done.

Commissioning responsibilities for hepatitis C services, from prevention and testing through to treatment and care, are complex with multiple commissioners and providers.

Often, we know precisely what needs to be done, but the challenge lies in how we actually achieve it.

PHE is establishing a cross-agency expert group on viral hepatitis to provide strategic direction and advice around hepatitis C (and other viral hepatitides).

This group will be a forum to explore operational and implementation issues to help find the best ways to overcome barriers at all levels and make improvements to delivery of services.

High up on the agenda will be the urgent need to find those who remain undiagnosed. Injecting drugs with unsterile injecting equipment, particularly needles and syringes, can put people at risk of hepatitis C infection, even if they injected only once or twice in the past.

Data presented in our report suggest that only around one half of people who inject drugs are aware of their infection.

Others at risk of hepatitis C include those who have received blood transfusions before September 1991 or blood products before 1986 in the UK.

People who originate from countries with a higher prevalence of infection, such as South Asia, are also at risk, often following medical or dental treatment abroad with unsterile equipment.

Encouragingly, there has been a steady increase in the number of diagnosed infections over the past two decades, reaching a peak of 11,605 reports in 2015. An increase in testing is also observed in sentinel surveillance, which suggests a near 20% increase overall and around a 25% increase in testing via GP surgeries between 2011 and 2015.

Acknowledging that donors who disclose a history of injecting drugs are permanently deferred from donating blood in the UK, disproportionately high numbers of hepatitis C infections are observed in new donors from South Asia, and promisingly, sentinel surveillance suggests that testing in people of Asian or Asian British origin has risen by just over 16% between 2011 and 2015.

Data in our report, however, suggest that numbers of new hepatitis C infections have remained relatively stable over recent years and, worryingly, less than half of people who inject drugs report adequate needle/syringe provision for their needs; 17% also report sharing of needles and syringes in 2015, similar to levels reported over the previous 5 years.

Looking forward, with operational delivery networks through which treatment can be delivered; a national hepatitis C report with metrics to help us monitor our progress/the impact of our interventions; and a new national strategic group on viral hepatitis to bring together key partners involved in the prevention, testing and treatment of hepatitis C; we have a firm foundation from which to work towards eliminating hepatitis C as a major public health threat in England.

Interested in receiving more blogs like this? Please sign up for updates via email or follow us on Twitter.

1 comment

Comment by Sarah posted on

Shame the treatments that are successful aren't offered to everybody and some patients are forced to finance their own treatment and monitoring.