Next week PHE will host our fifth annual conference at the University of Warwick. As we prepare to bring together the public health community I’m taking a look with PHE colleagues at three key topics which are at the forefront of public health and which cut through many of our conference sessions: the impact of world leading science on the public’s health, health inequalities and finally the economic case for prevention, which I explore in this blog with Brian Ferguson.

Ask public health people what motivates them professionally and the answer for most might be the opportunity to protect health, promote health and wellbeing or to reduce health inequalities.

But we also know from talking to colleagues across the NHS, local government and national government that their budgets must work harder and harder, year on year.

So alongside their focus on improving the lives of the people they serve, they must debate which initiatives provide the best value for money or even save public money.

More than ever before, ‘public health’ has to make the strongest possible economic case for what we do.

Whether at next week’s PHE conference, in NHS meetings or in council chambers across the land, everyone is discussing ROI.

PHE’s health economics team has been developing work in this area over the last 2-3 years, commissioning and producing a range of products aimed at helping local government and the NHS to make investment decisions based on the best available evidence, and this work continues.

Making the economic case

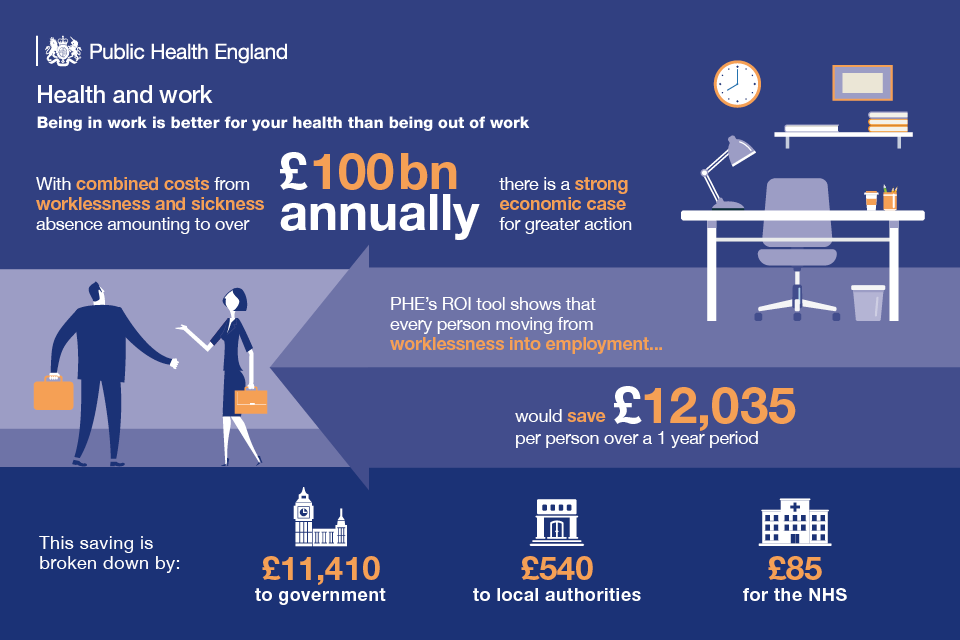

It is widely acknowledged that poor lifestyle behaviours as well as wider determinants of health place a significant burden on public finances now and in the future, and the evidence shows that a large number of prevention programmes represent value for money. Therefore there is a strong economic case for greater action.

For example, our work shows that moving a person from unemployment into employment would save £12,035 per person over a one-year period.

Another example we can use to make the economic case is analysis of a ‘targeted supervised tooth brushing programme’. This initiative provides a return of £3.06 for every £1 invested after 5 years and £3.66 after 10 years. On this occasion we are taking into account NHS savings, increased earnings for the local economy and improved productivity.

There is also excellent evidence to support investment in tobacco control services. Over a lifetime, for every £1 spent the return will be £11.20 when impacts to the local economy, wider healthcare sector and QALYs are considered. When omitting the health effects (measured by QALYs), there is still a saving of £1.90 for every £1 spent.

Every £1 spent on drug treatment services saves society around £2.50 in reduced NHS and social care costs and reduced crime in the short-term (85% due to reductions in offending).

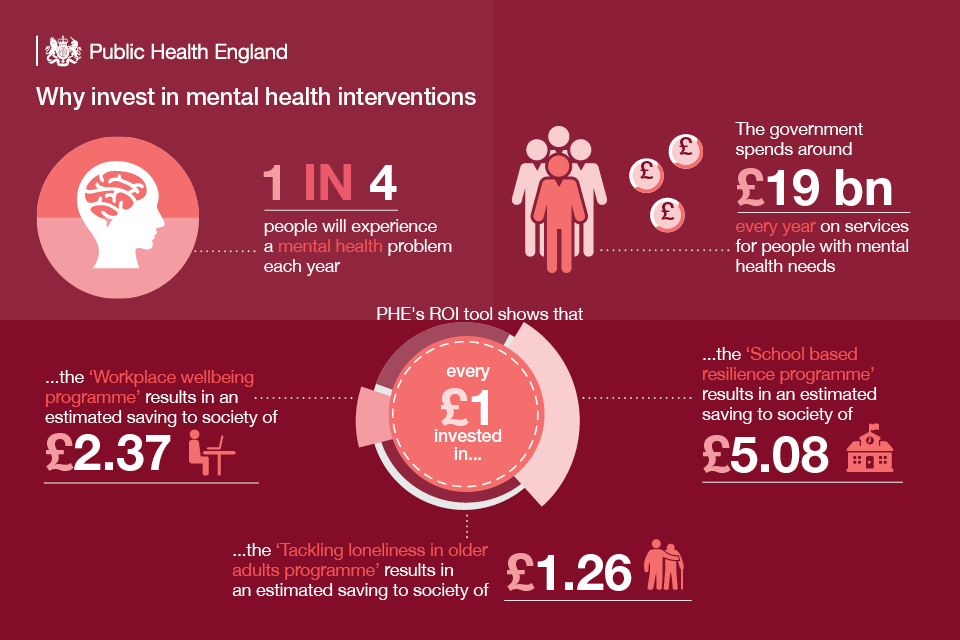

And as we recently flagged as part of a suite of mental health resources, initiatives which prevent mental health problems can yield a good return on investment. We looked at interventions such as school-based resilience programmes, workplace stress programmes and support for people in debt.

Return on investment (ROI)

In all these examples the calculations vary according to, for example, what benefits are included and over what time period, and we must be clear about this when we make the case for each initiative.

In simple terms, ROI encompasses the range of approaches which assess the value generated by an investment, compared to the resources put in.

And whilst preventing people from becoming ill has an intrinsic value to individuals, families and society, there are some key building blocks needed when undertaking any economic evaluation to ensure that it is applicable to your local setting.

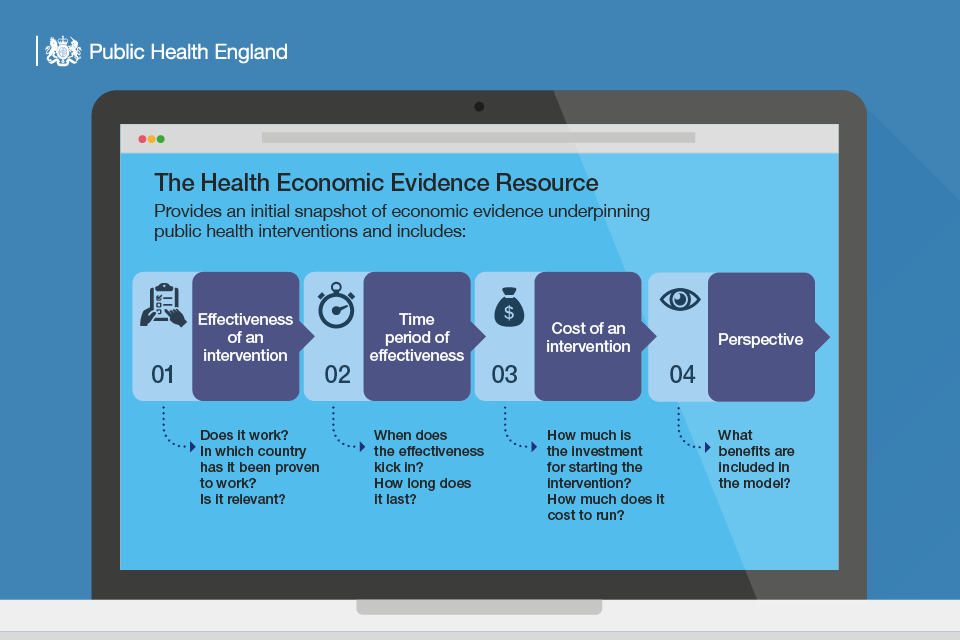

- Firstly effectiveness. It may seem an obvious point but we need to look at whether an intervention works, including looking at in which countries and with which population groups has it worked to understand if it is relevant to your setting.

- Secondly the time period of effectiveness is important. When does the impact kick in and how long does it last?

- Thirdly we must look at the cost of the intervention, both the investment to set it up and the ongoing running costs. This will then help to assess the cost-effectiveness or return on investment.

- Finally we look at what economists call the ‘perspective’ of the analysis - which specific costs and benefits are included and to whom. Sometimes this will involve a relatively narrow focus on short-term cost or efficiency savings, but more typically will involve a longer and broader societal perspective to quantify health benefits (e.g. by using quality adjusted life years, QALYs) and place a value on these alongside other benefits.

In the new ‘Health Economics Evidence Resource’ (HEER) being published next week at our annual conference, we have pulled together the best available cost-effectiveness and return on investment evidence from the literature to help both locally and nationally in developing the economic case for investing in prevention.

This focuses initially on the areas of the public health grant. The HEER is an initial snapshop of economc evidence that will be updated annually by PHE in a live, easy-to-use format.

What’s next?

In our most recent Business Plan we outlined our intention to do more work to make the economic case for prevention, working to identify interventions and opportunities which make better investments for public services and society as a whole.

This includes linking with national Government as well as supporting local government and the NHS to maximise the value from every local pound.

Please take a look at recent ROI work in areas such as diabetes prevention and colorectal cancer as well as the mental health resource mentioned above.

And look out for more of this analysis and the launch of further tools from us over the coming months, in areas such as early years interventions, falls prevention and air pollution.

We will use opportunities like our forthcoming conference to keep this important debate going, ensuring that a focus on ROI can help us meet our ultimate goal of protecting and improving the health of people in England.

4 comments

Comment by Sarah Cowley posted on

Thanks for this - but nothing about early years prevention? That's where greatest savings can be made.

Comment by Mark Gamsu posted on

Glad to see you are carrying on the good fight Brian Ferguson- I was particularly pleased to see that you had included economic case for welfare rights/debt advice - Mark Gamsu

Comment by Mary E Black posted on

Really interesting and useful work Brian. The challenge is that the cost saving is accrues to different budgets than the intervention.

Also people and decision makers are not always logical in their choices and view present and future benefits differently.

Comment by Caroline Vass posted on

Really interesting but very much using the traditional (acute) medical approach. There are additional / different considerations in prioritising public health services which are not addressed here. For example the degree of effectiveness of population wide interventions which require a high level of political commitment (highly effective) compared to interventions which require low political commitment but considerable individual effort (less effective). See also Mary's comment above. It is not clear the degree to which these issues are considered in this prioritisation tool? In the prioritising of public health interventions I feel that we need to consider more than just an economic case.