You may have seen recent news stories that suggest ‘Victorian’ or ‘Dickensian’ diseases are making a comeback.

The reality is that they have never gone away, and it is only through the combined efforts of society, informed by sound science and public health policy, that the impact and spread of a huge variety of infections, from scarlet fever to salmonella, tuberculosis (TB) to tick-borne infections, measles to meningitis, has been contained.

Developments such as clean water, wholesome food, education, the arrival of antibiotics and vaccinations have meant progress over the last 150 years at containing and treating disease spread has been substantial.

Nevertheless, there are still infections that from time to time can re-emerge or be re-introduced into the population to cause major and minor public health issues, so reports that some of these are making a comeback aren’t quite accurate.

In the UK some diseases have been eliminated and others still circulate at low rates and can periodically increase or re-emerge as a problem.

In this blog, we walk through the facts about the top diseases that affected or killed many people in the Victorian era and at other points in history.

Typhoid

Typhoid during the Victorian era was incredibly common and remains so in parts of the world where there is poor sanitation and limited access to clean water. No section of society was spared – Prince Albert the husband of Queen Victoria contracted typhoid and died from it.

Typhoid is caused by Salmonella typhi and is usually spread by the ‘faecal oral’ route – the organism is in urine and faeces and a person becomes infected by eating or drinking contaminated food or water. Globally, it is estimated 1 in 5 people with a typhoid infection die if left untreated.

Access to clean water and food is the main way of controlling this disease. Good personal hygiene - washing hands after using the toilet and before preparing food are also important to prevent spread. These seemingly simple steps, alongside access to clean water and wholesome food have helped significantly reduce the spread of typhoid fever in Britain.

Typhoid is uncommon in the UK now with an estimated 500 cases diagnosed each year.

Most people develop the infection after travelling abroad to places like Bangladesh, India or Pakistan where typhoid is circulating at higher levels. It may be prevented by vaccination, if someone is planning to travel to somewhere that typhoid fever is widespread, and it can be treated with a course of antibiotics. It is unusual for people to die due to typhoid in the UK.

Scarlet fever

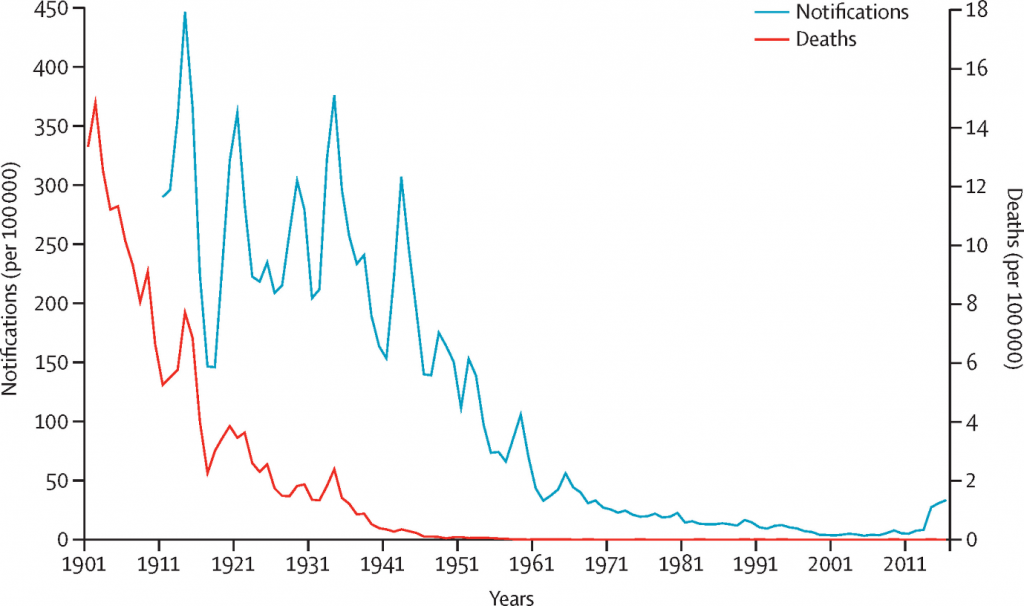

In 2018 there were over 30,000 cases of scarlet fever in England and Wales – the highest number of cases reported since 1960. Numbers of cases dramatically reduced over the course of the last century, likely to be due in part to improved living conditions, along with the introduction of antibiotics.

Scarlet fever is a highly contagious disease that mainly affects children, but it is not usually a serious illness and is easily treatable with antibiotics to reduce the risk of complications and spread to others.

It was still very common in the early part of the 20th Century. The Lancet Infectious Diseases paper shows that during the 1914 epidemic peak, around 165,000 notifications and 2800 deaths from scarlet fever were recorded.

In 2014 fewer than 5% of patients with scarlet fever were admitted to hospital and there were no deaths caused by scarlet fever illustrating the far more severe consequences of scarlet fever in the first half of the 20th century than today.

There have been some reports in the media that the recent rise in cases of scarlet fever is linked to austerity. Our data doesn’t show higher rates of scarlet fever in most deprived areas in England, rather that there have been increases across the country. As such, this speculation needs to be treated with caution with more studies needed to fully investigate.

We are investigating possible explanations as to why there have been more scarlet fever cases over the last few years, by studying the strains of bacteria causing disease, and studying the spread of infection in different settings and patient groups.

Tuberculosis

At the dawn of the 19th century, TB killed at least 1 in seven people in England. General improvements in health such as pasteurisation of milk (TB caused by M bovis from milk used to kill up to 2,000 people a year) meant that faster diagnoses and treatment with effective antibiotics became the mainstay of TB control.

Today, less than 6% of those with TB are killed by the disease and we are at the lowest numbers of TB ever, with just under 4,672cases reported in 2018. This substantial decline was brought about by collaborative working with partners across the health and social care system and represents a significant victory for public health in England.

But, we can’t take our foot off the pedal – globally WHO report that TB is still the number one infectious killer, especially in more deprived communities, and work is still needed if we are to see TB rates continue to decrease in England and across the world. PHE, DFID and DHSC have been working with the UN to accelerate efforts to end TB worldwide.

Cholera

The severe dehydration resulting from the diarrhoeal illness caused by cholera can kill healthy adults within hours, unlike the diarrhoeal illness cause by organisms such as campylobacter and rotavirus. The last four major outbreaks of Cholera in England were between 1832 – 1866 and resulted in thousands of deaths over short spells of time.

It is now very rare in the UK and any cases are associated with travel to countries where cholera is still a problem.

The public health turning point in the Victorian era came when London physician John Snow identified that cholera was water borne and associated with water contaminated with human faeces from people suffering from cholera. This led to the great Victorian projects that were to ensure the UK had clean water and a network of sewage systems – both of which are key public health measures.

There are still cholera outbreaks in other parts of the world and it remains a global public health concern. Since 2010 there have been outbreaks in Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Algeria, and Yemen to name a few.

World Health Organisation provide very comprehensive prevention and control recommendations. PHE Porton are currently looking at the effectiveness of different disinfection methods against the responsible bacteria, V. cholerae, with the aim of providing better options for prevention of transmission of the disease.

It is very easy to avoid cholera while travelling to affected areas by only using or drinking water that has been boiled or bottled and washing your hands with soap and water before eating or drinking. There is also a vaccine available but most people do not need it.

Whooping cough

Before the introduction of routine immunisation in the 1950s, whooping cough used to affect tens of thousands of people. Thanks to vaccination this has dropped dramatically but the infection hasn’t gone away completely. Whooping cough is a cyclical disease which can peak every 3-4 years.

Despite the success of the vaccine programme, an increase in cases has been observed in recent years with almost 10,000 laboratory confirmed cases reported in 2012.

Other countries have also seen increases in cases which is thought to be due to a number of potential factors including increased professional awareness and development of and access to new tests to diagnose whooping cough. In addition, the change in vaccine from whole cell to aceullar vaccine is also considered to play a role.

Whooping cough affects all ages, but for unimmunised babies and very young children it can be particularly serious. In response to an outbreak in 2012, a vaccine programme for pregnant women was introduced to protect their babies from birth until they receive their own vaccines at 8,12 and 16 weeks of age. A further dose is offered at preschool age.

The vaccination programme for pregnant women has been shown to be highly effective in preventing cases and deaths from whooping cough in young babies under 2 months of age. It is therefore important to ensure and encourage women to get vaccinated, ideally between 20-32 weeks and for their babies to get vaccinated at the recommended time

The vaccine remains the best way to prevent serious disease and encouragingly more than 95% of 2-year-olds in England have received their whooping cough vaccines.

Rickets

Rickets is a deficiency disease caused by a lack of calcium or vitamin D. In the Victorian era it was widespread in low socio-economic areas of Great Britain, and it wasn’t until the early 1900s that researchers discovered how important sunlight and Vitamin D are in the development of bones.

Vitamin D is essential for healthy bones and most of us get enough from sunshine and a healthy balanced diet during summer and spring. During autumn and winter, those not consuming foods naturally containing or fortified with vitamin D should consider a daily 10 microgram supplement.

People who get no exposure to the sun or completely cover their skin when outside need to take a daily 10 microgram supplement throughout the year. Some people from ethnic minorities with darker skin may not get enough vitamin D during the summer and should consider a daily supplement all year.

Babies up to the age of 1 year should be given daily vitamin drops containing 8.5 micrograms of vitamin D unless they are consuming more than 500 ml of infant formula which is already fortified with vitamin D.

So, are ‘Dickensian diseases’ making a comeback?

Diseases that once were a death sentence for people in the 19th century are still diagnosed in modern day Britain. They never completely disappeared.

Nevertheless, for the most part in the UK, “Dickensian diseases” are at nowhere near the scale nor have the same impact on public health they once did. And the good news is that all can be preventable through either good hygiene, vaccination, or getting the correct nutrients.

It remains as important as ever that scientists and healthcare professionals investigate, manage, and inform the public about how to prevent against diseases that could have a serious impact on health and wellbeing.

You may also be interested in:

2 comments

Comment by John posted on

Surely the reemergence of syphilis deserved a paragraph?? We would have seen more cases of syphilis in the UK last week than all these other infections combined...

Comment by Switz posted on

"Surely the reemergence of syphilis deserved a paragraph?? We would have seen more cases of syphilis in the UK last week than all these other infections combined." i don't think so but we should really find a olution for all these problems.