Working in PHE centres, we see some illnesses regularly and have well-rehearsed processes in place. But some diseases are more unusual than others, for which we must be well prepared.

We don’t often hear about Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in this country – a respiratory illness caused by the MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which is mainly found in the Middle East. Since 2012 there have only been five cases confirmed in England. Yet, nearly 1,500 suspected cases of MERS have been tested in labs in the UK since 2012.

Despite the low number of confirmed cases we see here, it’s crucial that we can identify a true case of MERS when it presents and act to prevent further infections from occurring. As well as the importance of protecting public health, failure to control the infection can have a huge impact on a country’s economy.

The MERS outbreak in South Korea in 2015 is estimated to have cost the economy $10billion and led to a temporary reduction in the country’s GDP.

In August 2018, PHE confirmed a case of MERS-CoV in Leeds, in an individual who had recently flown to the UK from the Middle East. It was the first case in the UK since 2013.

As told by the experts

Mike Gent is the Deputy Director for Health Protection for Yorkshire and the Humber Centre, leading on all areas of health protection including communicable diseases, radiation, chemical and environmental threats.

Gavin Dabrera is a Consultant in Public Health Medicine at PHE’s National Infection Service, working on preparedness for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome and other respiratory infections including Avian Influenza.

Roberto Vivancos is a Consultant Medical Epidemiologist with over 12-years of experience in the field of health protection and has led the management and control of numerous outbreaks of infection and the public health response in a number of chemical incidents.

We caught up with them to take a behind-the-scenes look at the plans that kicked in across the country to protect the health of the wider public.

What is MERS and why is it so concerning?

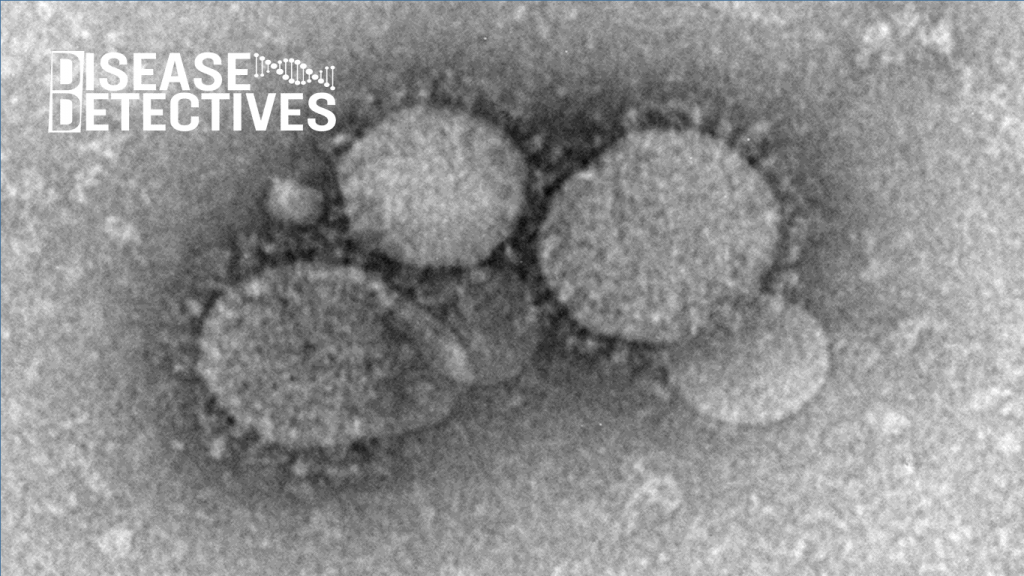

MERS is a rare but often severe respiratory virus. It can start with a fever and cough, which can develop into pneumonia and breathing difficulties. Sadly, around 40% of people who get the infection die of complications. Camels harbour the MERS-CoV virus and many, but not all, cases in the Middle East are associated with close contact with infected camels or camel products (such as raw camel’s milk).

While the causative virus isn’t as contagious as other viruses, such as influenza and measles, it does pose serious consequences, particularly in hospital settings, where the virus can spread quickly between vulnerable people if appropriate infection control measures are not in place.

How do you detect cases of disease like MERS?

MERS is considered to be a high consequence infectious disease (HCID) in the UK. An HCID is defined as a serious infectious disease that has the ability to spread in the community and within healthcare settings, has a high case fatality rate, is difficult to recognise and detect rapidly and lacks effective, specific treatments.

These features mean that coordination at a national level is required to ensure an effective and consistent response and as such, any clinicians that suspect a case of MERS must notify their local PHE health protection team.

In this case, the initial call came from the Emergency Department at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. Healthcare staff at the hospital promptly suspected MERS because of the person’s symptoms and travel history and immediately informed the Yorkshire and Humber Health Protection Team.

The clinical team quickly isolated the individual away from other patients and ensured staff wore appropriate levels of personal protective equipment to protect themselves and other patients. This quick action played a major role in limiting the risk of exposure and spread of the disease.

Once the diagnosis was suspected a throat swab was taken for testing and sent to one of PHE’s specialist regional laboratories. Scientists were able to confirm that the sample was positive for MERS-CoV within 24 hours.

What came next?

The first priority was to convene a national incident team to bring together experts from all the partner agencies involved. These included the relevant NHS Trusts and the Department of Health and Social Care. The benefit of this approach is pooling national expertise and agree the necessary actions to both treat the patient and protect wider public health.

A national incident was declared, led by our national team of respiratory experts in close collaboration with the local Health Protection Teams. As MERS is an uncommon, high-consequence infection, the national team provides specialist advice, and the local teams have the expertise and knowledge to respond to emergencies on the ground and liaise with healthcare stakeholders.

The patient was transferred to the Airborne HCID Treatment Centre at the Royal Liverpool Hospital, one of four national centres commissioned by NHS England in 2018 to treat cases of airborne HCIDs such as MERS, avian influenza and pneumonic plague.

The HCID treatment centres have the facilities to implement the robust infection control measures required for caring for individuals with MERS, as well as trained, specialist staff who provide expert care for these rare conditions.

Besides helping to coordinate appropriate care for patients, the primary role for the incident team is to agree control measures to prevent further cases of the disease occurring. In this incident, contact tracing played a huge part in the incident response.

This involves identifying anyone who may have come into contact with the case whilst they were infectious, alerting them to the symptoms of the disease and letting them know what to do, should they develop any symptoms. It was also important to keep global agencies such as the World Health Organization informed.

What did contact tracing involve?

Where contact tracing is involved, no stone can be left unturned and we’re constantly aware that the clock is ticking. It’s crucial that the process is timely, detailed and thorough, and this means closely examining the movements of the person in the days they were infectious.

A missed close contact could mean the disease is spread elsewhere in the country – or even internationally. Over the course of the investigation, over 70 people who could have been potentially exposed were contacted.

There were three key groups of contacts that our teams across the country had to trace:

- The individual’s family

- Passengers on the plane who were in very close proximity to the individual (as air filter systems protect other travellers)

- Healthcare workers who had been in contact with the patient (including before MERS was suspected)

We monitored those who came into contact with the patient while they were travelling from the Middle East or while in Leeds and, for 14 days after their last point of contact with the patient. 14 days is the longest amount of time it would take for someone to become sick after being exposed to the virus.

We asked these people to look out for relevant symptoms, such as fever, cough and difficulty breathing, and to contact their local Health Protection Team if symptoms occurred. Appropriate medical help and assessment could then be provided quickly if necessary.

Those who were in sustained, close contact with the individual before MERS was suspected and the necessary, specific infection control measures were put in place, such as healthcare workers at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and the individual’s family, were at an increased risk. Therefore, we asked them to stay at home for 14 days while we actively monitored their health.

We are very grateful to all of the healthcare staff involved in this incident – not just for the care they provided, but for their patience with the monitoring process. Their cooperation with this ensured that we could contain the risk of transmission as much as possible.

How complex was the flight contact tracing?

Plans for contact tracing plane passengers were in place from previous MERS cases, but it is still a large undertaking. To establish whether there had been any onward transmission of MERS-CoV during the flight from the Middle East to Manchester, passengers who were sat in the vicinity of the individual were contacted by the PHE North West Health Protection Team.

Many of the passengers were dispersed throughout the UK, and PHE’s Health Protection Teams were enlisted from up and down the country, to ensure the passengers received the relevant information and advice.

Were we prepared for this happening?

While we’ve only seen 5 cases of MERS confirmed in the UK to date, we have well established processes to implement in the event of a confirmed diagnosis. Our processes are based on learnings from other countries, such as Saudi Arabia, who have seen 1983 cases since 2012.

Our team carries out surveillance of MERS cases across the globe, in order to help with planning and preparations in the UK. This includes carrying out awareness raising with the public and with healthcare professionals each year around the time of the Hajj – the annual pilgrimage to Mecca – where there is a spike in travel to and from the Middle East.

This coordinated response involved over 100 people working across Public Health England, including roles in contact tracing, infection control advice and laboratory testing, as well as many staff across the NHS. By working alongside the HCID, we not only helped to ensure that the individual received the best possible care, but also that there was no onward transmission of the disease.

Four weeks after their diagnosis, the individual had recovered from their infection and was free to leave hospital and join their family in the Middle East. While the risk of transmission of MERS-CoV to UK residents in the UK remains very low, it is important that we remain prepared for future imported cases and for other high consequence infectious diseases that need to be managed in a similar way.

Read more from our Disease Detectives series

Responding to the public health challenge of the Rohingya crisis