Updated 11 June 2021

While for many hot weather is something to be welcomed, high temperatures have significant health consequences and are associated with increased illness and deaths in England. These health impacts are largely preventable but once temperatures start to rise the window of opportunity for taking action is very short. In total, summer 2020 observed 2,556 all-cause excess deaths during episodes of heat. This is the highest heatwave associated all-cause excess mortality observed since the introduction of the Heatwave Plan for England in 2004.

The current COVID-19 pandemic will amplify the health risks from heat. Equally, in the context of the pandemic, we will need to take actions differently to prevent heat related harm to health.

In preparation for summer 2021, PHE has developed a slide set to outline intersecting COVID-19 and hot weather risks and to highlight changes to the usual actions in the Heatwave Plan for England in light of the pandemic. PHE has also published further supporting resources, including a ‘Beat the Heat: Coping with heat and COVID-19’ leaflet and poster. All these resources are available on the Heatwave Plan for England Collection Page.

How does heat affect the body?

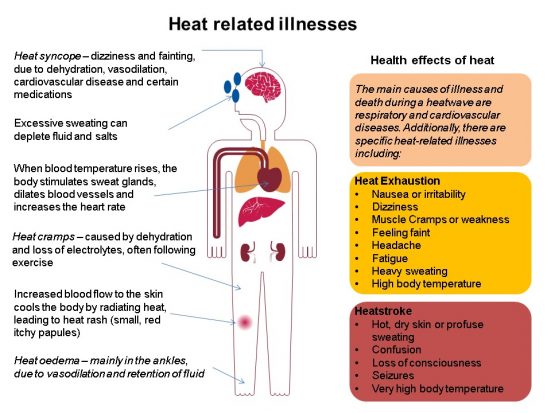

Exposure to high indoor and outdoor temperatures can result in a range of mild to severe health impacts. The main causes of illness and death associated with hot weather are respiratory and cardiovascular, as hot weather means our bodies must work harder to maintain an inner core temperature, thereby putting extra strain on the heart and lungs.

This extra strain - coupled with fluid and salt loss through sweating - can lead to specific heat-related health effects and illnesses.

Who is vulnerable?

While everybody is at risk from the health consequences of heat, there are certain factors that increase an individual’s risk during a heatwave. These include:

- older age: especially those over 75 years old, or those living on their own and who are socially isolated, or those living in a care home

- chronic and severe illness: including heart or lung conditions, diabetes, renal insufficiency, Parkinson’s disease or severe mental illness

- inability to adapt behaviour to keep cool: babies and the very young, having a disability, being bed bound, having Alzheimer’s disease

- environmental factors and overexposure: living in a top floor flat, being homeless, activities or jobs that are in hot places or outdoors and include high levels of physical exertion

Intersecting risks

Several of the risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease overlap with key heat risk factors, including older age and those with chronic heart and lung problems. As with heat, COVID-19 infection affects the heart, lungs, kidneys, and is also associated with systemic inflammation.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions more people will likely be indoors and/or shielding and may need additional health and social care support to cope with the hot weather. People who are managing a COVID-19 infection at home may struggle to keep cool, particularly if they are running a fever. Recovery from a COVID-19 infection can take some time. Those recovering at home after a severe COVID-19 infection may have some ongoing organ damage, which means that they will be more vulnerable to the effects of heat than usual, and so it is especially important that they stay cool and hydrated.

What should I do?

Evidence suggests people often don’t consider themselves at risk of dehydration and overheating. This is why our usual advice focuses on reminding people to keep an eye on vulnerable friends, relatives and neighbours during a heatwave. It is important that we continue to do this whilst also taking care to reduce the risk of transmission of the infection; stay in touch over the phone, if you do need to call in to check on someone make sure you follow the guidance on providing care to others – keep your distance, make sure you wash your hands when you arrive and when you’re leaving, and use a tissue if you cough, or cough into your elbow.

If you are feeling unwell with symptoms of COVID-19 yourself, you should not visit anyone you are providing care for and should make alternative plans for their care. If you are finding it difficult to organise alternative care you can ask your local authority or health care provider to help.

Keeping hydrated is vital to replace fluid loss through sweating, but it also helps cool the body and prevent heat exhaustion. Drink plenty of fluids and avoid excess alcohol. Water, lower fat milks and tea and coffee are good options.

Many of us will be spending more time at home this summer so knowing how to keep your home cool is useful. It is particularly important if you or someone in your family is in a vulnerable group or self-isolating. Think about how you might be able to keep your home cool:

- shade or cover windows exposed to direct sunlight, external shutters or shades are very effective; internal blinds or curtains are less effective but cheaper

- move to a cooler part of the house, especially for sleeping

- it may be cooler outside in the shade, consider a visit outdoors as a way of cooling down; but keep your distance from others

- open windows when the air feels cooler outside than inside, for example, at night. Try to get air flowing through the home

- natural ventilation can help keep your home cool without increasing the risk of spreading infections. Fans may be used in domestic settings provided the temperature is below 35°C and national guidance on self-isolation for COVID-19 is followed (i.e. you should avoid contact with others in the household if you have a COVID-19 infection). Aim the fan so that air is pushed towards the outside (e.g. towards an open window) and do not aim the fan directly at the body

- turn off lights or electrical equipment are not in use, as these can increase the temperature of your home. Check that fridges and freezers are working properly and ensure your central heating isn’t programmed to come on

If you are not self-isolating at home and do not have any symptoms of COVID-19, you may find it helpful to spend time in a cool place outside if this feels cooler than the temperature indoors, such as some shaded green space. Remember to use public spaces considerately and respect social distancing guidance, so that people who are vulnerable to heat and/or COVID-19 can use them safely. If you find it difficult to cool down your home or do not have access to a cool outside space, having a cool bath or shower and sponging the skin with cool water can also help.

Be aware of the signs and symptoms

Some symptoms of heat-related illnesses, such as a high temperature, headache, loss of appetite, feeling dizzy or shortness of breath can be similar to symptoms of COVID-19. If you or someone else feels unwell with a high temperature during hot weather, you should consider the possibility of heat-related illnesses such as heat exhaustion or heatstroke. If, however, you suspect that you have COVID-19 find out how to get tested.

If someone is showing signs of heat exhaustion they need to be cooled down. The NHS advises that there are four things you can do to cool someone down and they should feel better within 30 minutes:

- Move them to a cool place

- Get them to lie down and raise their feet slightly

- Get them to drink plenty of water. Sports or rehydration drinks are OK

- Cool their skin – spray or sponge them with cool water and fan them. Cold packs around the armpits or neck are good too

Stay with them until they are better and call 999 if the person is:

- No better after 30 minutes

- Still feeling hot and dry

- Not sweating even though they are too hot

- Showing a temperature that's risen to 40°C or above

- Experiencing rapid or shortness of breath or is confused, has a fit or loses consciousness

Any of these could be a sign of heat stroke which is a medical emergency and can kill.

If someone needs your help (for example in taking their temperature or to drink or cool down), you may need to be in close proximity to them . If you are in a health or social care setting you should follow your organisational guidelines on Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Outside of clinical and care settings, remember to protect yourself and others by washing your hands with soap for 20 seconds or by using an alcohol hand-rub before and after helping someone, and try to ensure that you don’t cough or sneeze over them.