Prisons are complex settings in which to deliver healthcare, and people in prisons and under probation service supervision have higher levels of health and social care needs than others in the community.

This is due to multiple overlapping factors such as adverse childhood experiences, a history of poor housing and a lack of engagement with healthcare.

People in prisons are also at greater risk of exposure to, and more vulnerable from, the effects of external health threats such as infectious diseases and may require more targeted interventions to overcome specific barriers in identifying, accepting, and accessing services.

There are approximately 82 000 people currently within the prison system, although the total number of people having contact with the prison system is higher.

In England, the National Partnership Agreement (NPA) for 2022-2025 brings together a wide variety of agencies, including UKHSA, to outline agreed priorities to improve outcomes for health across this population.

This includes promoting and increasing access to preventative, diagnostic and screening programmes for infectious diseases such as hepatitis.

Understanding the burden of hepatitis infection in prisons

Viral hepatitis, notably hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV), is spread through infected blood.

HCV can be cured with treatment. Though HBV is incurable it can be treated, and virus levels reduced.

If left untreated, hepatitis can cause liver damage (cirrhosis), liver failure, and increased risk of liver cancer.

In 2021, around 75 000 people in England were estimated to be living with chronic HCV; 89% had a recent or past history of injecting drugs.

People in prisons have an increased history of injecting drugs, with an estimated 40% of people in prison having injected drugs prior to arrest.

Though estimates vary slightly, the prevalence of HCV antibody (denoting past or current infection) in prisons is approximately 6%, compared to 0.7% in the community.

Furthermore, the risk of reinfection is higher amongst people in prisons than the general population, due to disproportionate levels of injecting drug use among the prison population and ongoing exposure to risk.

Elimination and prevention of hepatitis

The UK Government has committed to the World Health Organisation’s goals to eliminate viral HBV and HCV as a public health threat by 2030; prisons have been identified as a priority setting for HCV testing and treatment to achieve elimination.

The National Partnership Agreement supports case finding of people with HCV within the prison estate and ensures access to specialist treatment and peer support structures to support progress against the elimination target by 2030.

UKHSA guidance recommends that the most effective way to prevent HBV is immunisation and NHS England have commissioned a service offering everyone entering prison in England a full course of HBV vaccination.

For HCV, there is strong evidence of effectiveness of needle exchange programmes in prison to prevent the transmission of blood borne viruses.

This is not yet established in English prisons, though His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) do recommend that prisons maintain stocks of bleach tablets for disinfection of needles.

Hepatitis diagnosis and treatment

Since 2014 all English prisons have offered opt-out bloodborne virus (BBV) testing for people entering prison, aiming to detect HBV and HCV, as well as HIV, and refer people for further diagnostics or treatment as needed.

In March 2023, of those who accepted testing and were in the same establishment after 2 weeks, 71% of people were provided with Ab testing within 2 weeks of reception (NHSE data).

This is a significant increase from the pre-introduction levels of 5.3% in 2010, but is slightly lower than the target uptake of 75%.

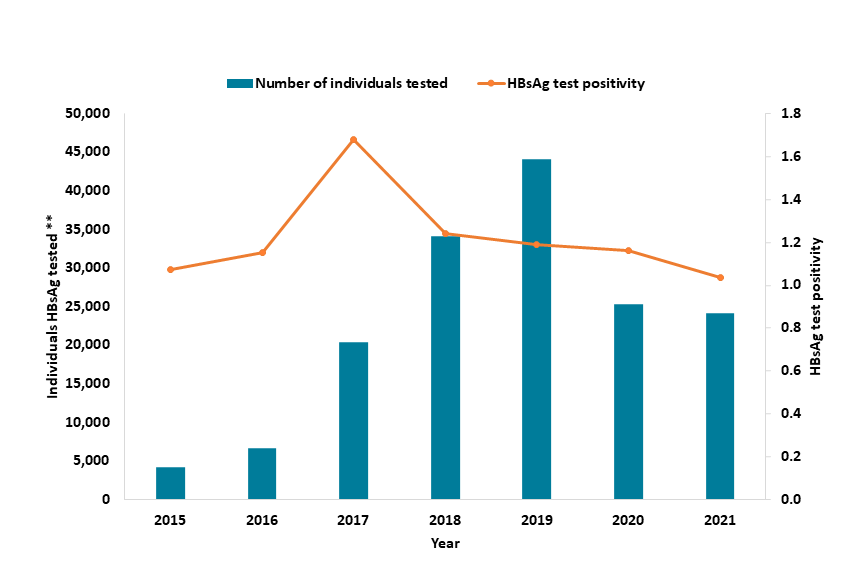

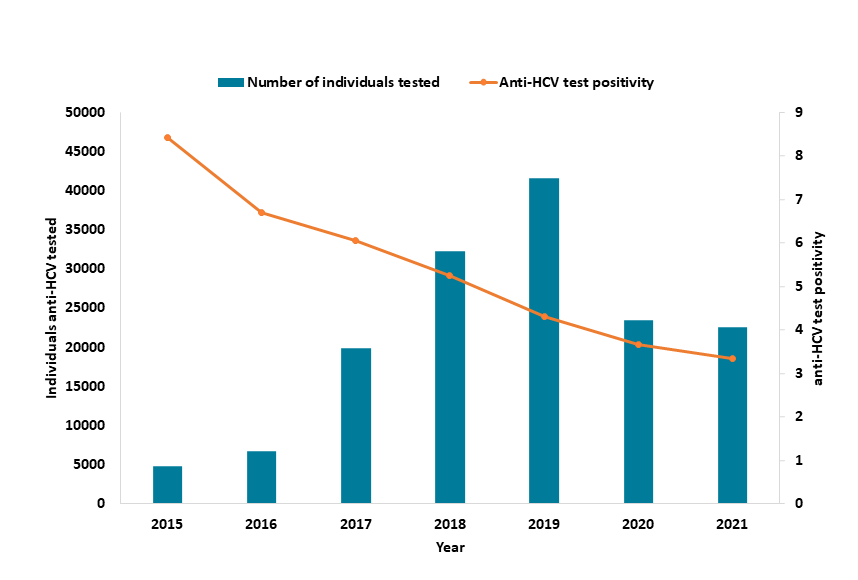

UKHSA’s surveillance programmes suggest the number of individuals tested for hepatitis in prisons rose dramatically between 2015 and 2019. Testing figures decreased in in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and have yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

This is attributed to a range of initiatives, including High Intensity Test and Treat programmes, which help people start and continue treatment. This programme aims to mass test everyone in prisons for HCV and fast track them onto treatment within a 2-week timeframe.

Peer support models also help in providing support to others and adherence to treatment protocols.

Data challenges

Several data challenges prevent a better understanding of hepatitis prevention, diagnosis, and treatment in this population group. To that end, UKHSA is working with NHS England and partners to improve data on:

- Current HBV immunisation coverage and uptake of harm reduction strategies

- Demographic data on opt-out BBV screening, point of care testing initiatives such as HIITs, and immunisation to understand barriers to uptake

- Developing linked data sets and monitor treatment adherence beyond an individual’s time in prison

UKHSA are also supporting the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities in the further development of Spotlight, a data dissemination tool. This data collection will build on existing and improved datasets to help health agencies better understand the needs of this, and other, inclusion health groups.

Looking forward

We remain committed to reducing transmission of blood borne viruses and achieving more equitable outcomes – this includes opportunities within prisons for healthcare interventions to reduce infections.

UKHSA will continue to work towards hepatitis elimination targets through continued collaboration, implementation of the upcoming NPA, and applying best evidence and data.

We will also share our learning and highlight what can be done across the system to achieve more equitable health security outcomes for these populations.