This blog is part of Disease Detectives, a series which showcases PHE science. This piece comes from our Emerging Infections and Zoonoses team and was written by PHE epidemiologist Jennifer Lloyd.

Ebola! Marburg! Zika virus! Black Death!

These are words you may have heard quite a lot these past few years. Almost every day, somewhere in the world, there are stories in the media about diseases which can kill us or rumours of a new “eye-bleeding disease”. While these might be entertaining to read, they are very frustrating for us as Emerging Infections scientists, because they spread a lot of misinformation and fear.

The truth is these diseases have been present in parts of the world for years. They are called emerging infections. Emerging infections are either newly recognised diseases or diseases that are increasing in a specific place, or among a specific population. They can be transmitted in many ways, including by insects, water, animals, or from person-to-person. Most emerging infections are zoonotic, meaning they spread from animals to humans.

With the increased movement of people around the globe and increased urbanisation, the likelihood of coming into contact with new/emerging diseases has increased. This is because humans come into contact more readily with creatures that harbour these infections, whether they are mosquitoes, ticks or animals. And the more we come into contact with them, the more likely we are to become infected.

While this is all very interesting, at this point you may be thinking to yourself, but why should I care? The media stories are just rumours. There has been nothing in the news lately about Ebola or Zika virus outbreaks. Those diseases are gone, aren’t they?

Well, no. Most of these emerging infections are present in the animal or insect population for years before (and after) an outbreak occurs. They may even cause human cases that aren’t detected. Because of this, in the past some outbreaks haven’t been recognised until they were already established. That’s where we come in.

Epidemic Intelligence

Here in the Emerging Infections and Zoonoses section, it’s our job to detect these events as early and quickly as possible to raise awareness for clinicians, labs and across government. To do this, we conduct epidemic intelligence. This is a process of horizon scanning (a form of surveillance) that is used to identify and gather information about current outbreaks and incidents of new and emerging infectious diseases, occurring anywhere in the world.

This means that we spend half of each day combing nearly a hundred sources on the internet for rumours of diseases and “unusual incidents” around the world. We look at everything – official reports from international organisations like the WHO and Ministries of Health, international and local media, and even Facebook and Twitter. We use these because the majority of the world’s first news about infectious disease events now comes from unofficial sources, including newspapers, social media and other internet resources.

Why rumours matter to us

One of the main things we look for are rumours; rumours from local or social media of undiagnosed diseases, unusual events, haemorrhagic fevers (serious viral infections characterised by sudden onset of fever and bleeding) and/or large numbers of deaths. When we find something, we record it in our database and then go to work searching other sources for more information.

Then we conduct a risk assessment to determine if further escalation is necessary. If the answer is yes, then the information is communicated within PHE and to appropriate people within the UK government. We help them gain awareness of disease events around the world and provide expert advice on situations that might get out of hand.

So how does it work

Horizon scanning becomes even more important when working with an emerging infection, like Zika virus, as every day our knowledge of this previously little known virus grew. As at the start of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in March 2014, our epidemic intelligence system picked up an outbreak of undiagnosed illness in Brazil before it was officially confirmed as Zika virus. We first detected media reports about an undiagnosed outbreak of fever/rash in Brazil in early 2015 - you can see the WHO Zika timeline here. Zika virus in Brazil was first confirmed in May 2015. Based on what we knew about other Aedes mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue and chikungunya, we were sure that this outbreak would quickly spread far and wide, but no-one anticipated the impact Zika would have on an unborn child.

With a situation like Zika, new information is received and reviewed on a daily basis to ensure we provide the most relevant and accurate information to those concerned about the situation. This could mean posting the information on relevant gov.uk webpages (such as the Zika collection), sharing it with our colleagues at NaTHNaC who provide country specific travel guidance or distributing it elsewhere.

If you want to read more from Disease Detectives, you'll find all future blogs here, and see more content shared through our social media channels. Twitter: @PHE_uk Facebook: Public Health England.

Mosquito image: CDC image libray (credit James Gathany)

Bushmeat image: Captured by the Emerging Infections and Zoonoses team

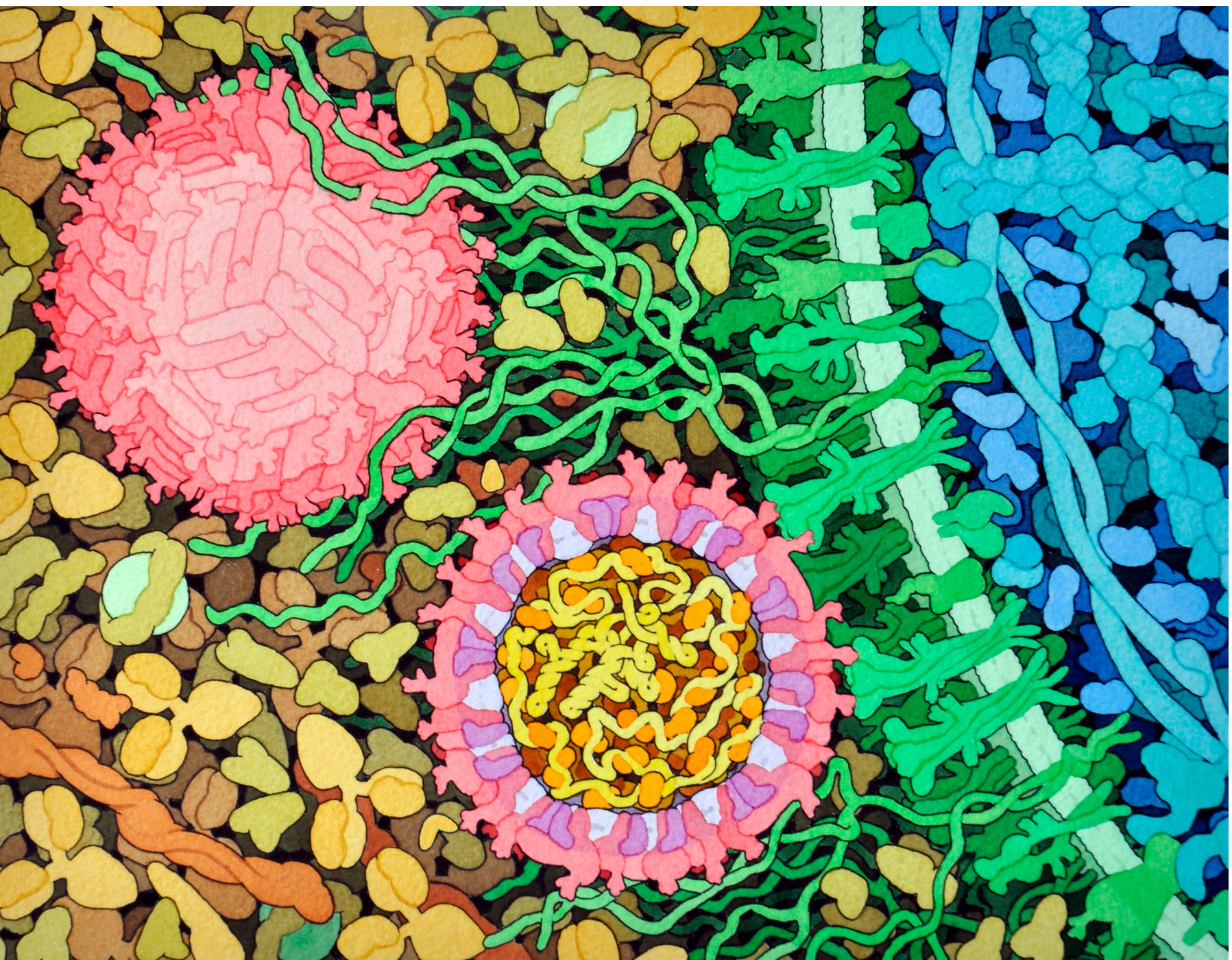

Zika illustration image: Wellcome Trust

1 comment

Comment by Andrew Taylor-Robinson, Professor of Infectious Disease Immunology, Central Queensland University, Australia posted on

Thank you for this informative primer on the work Public Health England performs regarding surveillance of the disease threat posed by emerging infections and zoonoses. I have a couple of related points to make.

There is a frequent misconception among the general public that disease is an inevitable outcome of infection – a scenario in which, say, you get bitten by a mosquito, you get infected, you become ill. It should be noted that for a lot of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, major illness is not the most probable outcome. Rather, for the majority of cases of arthropod-borne viruses (so-called arboviruses, typically transmitted by mosquitoes) such as Zika, mentioned in the article, as well as the far more widespread dengue, these manifest as subclinical infections. In such an instance, the person will not become ill and thus not even know that have been infected, and later, depending on circumstances, may develop immunity to reinfection. While not showing any symptoms, they do, however, become a reservoir of infection for potential transmission to a mosquito if one bites during the window of time the person is infectious. From an epidemiological perspective, the importance lies in the fact that the newly fed mosquito then may pass the virus to another, possibly susceptible, member of the local community if and when it next takes a blood meal.

In terms of communicating effectively to the general public, an emoji representing a mosquito will be released later this year by the Unicode Consortium to most smart phones and other electronic devices. There is a strong case that the addition of the mosquito to the emoji toolbox could help health authorities battle the health risks associated with these blood-sucking pests. For instance, it could be possible to combine emojis to communicate not only the risk of being bitten (potential nuisance value; mosquito emoji on its own, perhaps in multiples if there is a swarm) but also the threat of transmission of a vector-borne disease by being bitten (mosquito plus microbe emojis). Importantly, if used by, for instance, local government authorities, this would have the potential to convey rapidly and efficiently a widely accessible public health warning. Given the ease of use of the technology, this information could be regularly updated straight to mobile phones, especially via an app that sends notifications. As prevention is always better than cure, such e-health solutions should be increasingly embraced as a preventive medicine tool.