This week is Dementia Action Week – an important time to raise awareness of dementia, a progressive and ultimately fatal disease that many people have been touched by in some shape or form. Around 850,000 people are living with dementia in the UK and this figure is set to rise to over 2 million by 2050.

According to a survey by Alzheimer’s Research UK, dementia is the most feared health condition for people over the age of 55 – more than any other life threatening disease, including cancer and diabetes. It also presents a considerable health and social care challenge globally.

The dementia profile in England

PHE’s Dementia Intelligence Network (DIN) has published new data on the dementia profile, which shows the recorded prevalence of dementia in the over 65 population has shown a small but significant increase from 4.29% in April 2017 to 4.33% in September 2017. There has been a marked increase in the number of cases during the last few years, which is in part due to increased awareness and better diagnosis, as well as increasing numbers of older people.

The numbers are strikingly large and for each and every person with a diagnosis of dementia, the impact is enormous for not only themselves but also the people who share their lives.

Despite decades of research, there is currently no cure for dementia. However, it is now widely accepted that there are steps that can be taken to lower the risk of developing dementia.

A healthy lifestyle may help lower the risk of dementia and this entails:

- keeping physically active

- maintaining social engagement

- reducing smoking

- management of hearing loss, depression, diabetes and obesity

- active treatment of hypertension in middle aged (45-65 years) and older people (over 65 years)

Dementia and diet in the news

While the increase in public awareness and understanding of dementia is positive, it has also created an opportunity for media outlets to play on our fears by bombarding us with stories on ‘How to eat to beat dementia’.

There is no denying that the food we eat affects our health, now and in the future. In fact, a poor diet increases our risk of developing major diseases and is linked to one in five deaths globally. It is important to eat a healthy, balanced diet and be physically active to maintain overall health.

However, media stories on preventing dementia by avoiding or adhering to certain diets or foods, such as salads and blueberries, are particularly frequent and are constantly shifting. Further, the advice reported in these stories is often based on limited or poor quality evidence.

Although a holistic approach with the media working alongside healthcare professionals is a great way of influencing and informing people about dementia, the spread of misleading information can cause confusion and potentially harms people’s health as a result.

What is the official evidence and where do we get it from?

UK government dietary advice and recommendations have been largely unchanged until about two years ago, when new recommendations on sugar and fibre intake were made. UK government advice is based on reviews of evidence by an independent group of experts who form the UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN).

A recent report from SACN confirmed that there is no solid evidence that specific nutrients or food supplements can reduce the risk of developing dementia. However, there has been some observational evidence suggesting that diets that align broadly with UK healthy eating recommendations, such as the Eatwell Guide, may help reduce the risk of dementia.

What are the real facts?

Clickbait headlines could be distracting us from the risk factors that are underpinned by a strong evidence base – some of which we can control, others are non-modifiable.

Although it is possible to develop early-on set dementia under the age of 65, older people are living longer than ever before and age – not diet – is the biggest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. This is particularly the case for women, who typically live longer than men, which may explain why 65% of people living with dementia are women. Age is a leading risk factor as it often comes with changes such as weakening of the body’s natural repair systems. However, dementia is not an inevitable part of ageing.

In the same way that we cannot control age as a risk factor, we also cannot control whether we are genetically predisposed to developing dementia – although very few dementias are hereditary. This is also the case for ethnicity, as there is evidence to suggest that people of certain ethnicities, including South Asian, African and African-Caribbean populations, are at higher risk compared to white European populations.

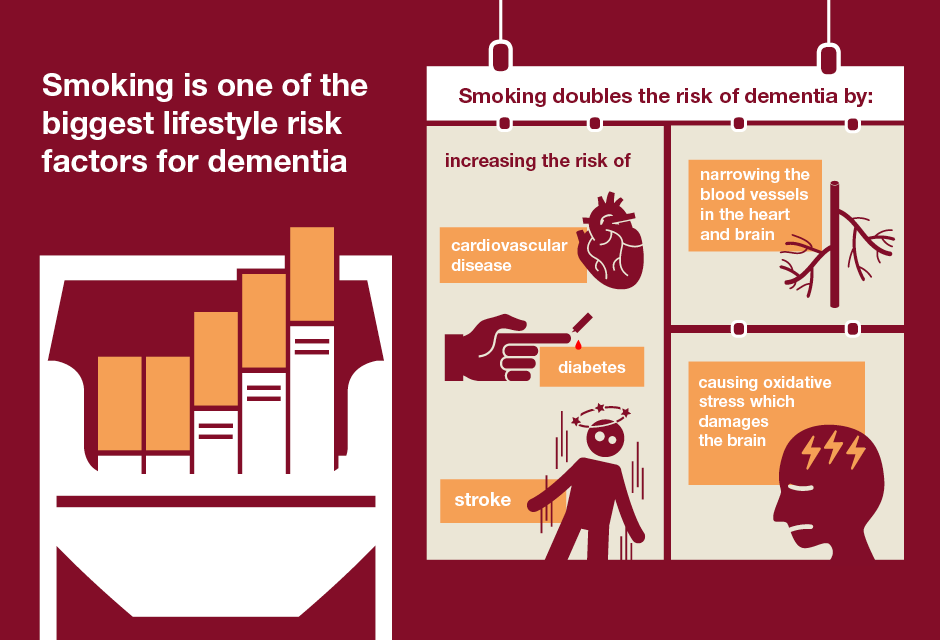

Smoking is one of the biggest lifestyle risk factors for dementia. It doubles the risk of dementia by increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and stroke, narrowing the blood vessels in the heart and brain, and causing oxidative stress which damages the brain. Therefore, one of the easiest ways to prevent dementia, and the other conditions smoking can lead to, is to quit smoking.

In order to make a real difference, well considered advisory messages that are based on sound evidence and consistency must be promoted. However, as well as understanding how to prevent dementia, it is also important to continue analysing how the disease is developing across the country. Being dementia aware is the least we can do to help the many people living with the disease all around us.

You can read more about preventing dementia in our previous Health Matters edition on midlife approaches to reduce dementia risk.