The SIREN study looks for answers to the most important questions about reinfection and COVID-19. This blog sets out how PHE has led the national effort to develop the science that helps decision-makers control the disease.

Starting the study

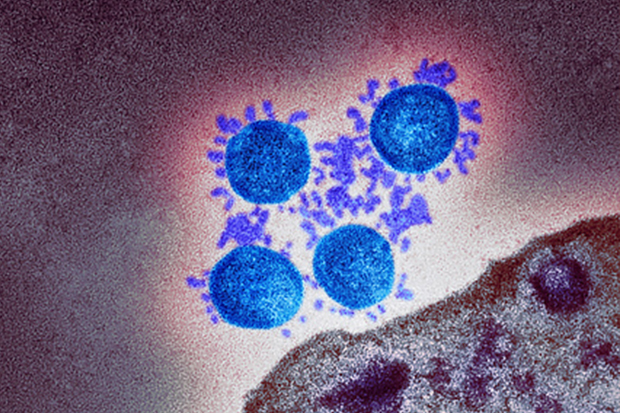

Since the outset of the pandemic, interest in antibodies and antibody testing has been huge. Antibodies are part of the human body’s immune response to an infection. They are a special protein which seeks, finds and attaches itself to an unwelcome invader, such as COVID-19. After the immune system has flushed out a cold, or cough, or COVID-19, these antibodies do not disappear.

Testing for the presence of COVID-19 antibodies can tell us if someone has had the virus before and advance our understanding of the spread of the virus. The more we understand about antibodies – and the more we know about COVID-19 reinfection more generally – the more information we have at our disposal to help decision-makers control the spread of the disease. Gathering this information was the overarching aim of the SARS-CoV-2 Immunity & REinfection EvaluatioN (SIREN) study when it was established as a National Institute of Health Research Urgent Public Health study in June 2020.

To develop this understanding at an unprecedented pace, it was decided that health workers up and down the country – doctors and nurse, porters and cleaners – would be the main participants of the study. It was developed on the back of smaller studies surveying PCR positivity and antibody positivity in healthcare workers which had demonstrated variable prevalence of acute infection (from 0.5-3% across hospitals) and high seroprevalence (prior infection) in healthcare workers. Within three weeks of study developement, PHE developed and rolled-out a system to survey the health workers, a system which could be scaled-up to allow for the thousands of volunteers that would be needed if the study was to be a success.

A nationwide effort

To reach those volunteers, teams at PHE focussed on the employers of the health workers themselves: NHS trusts in England. Within ten weeks after the first participant signed up, 74 sites were actively recruiting health workers and 10,000 of those health workers had answered the call to volunteer. As of early March 2021, there are 131 trust sites up and running and the cohort of volunteers is 49,282 strong and have also developed ways to incorporate smaller site specific studies for analysis through the UKRI funded Co-Connect study. All of this work by research teams across health systems in the four UK nations, and the public spiritedness of those who consented to participate, has helped PHE scientists to answer the big questions about this virus.

This has been no mean feat. The data generated by those volunteers pass through myriad organisations and has necessarily required diligent management. PHE’s data gathering, data management and database building have been critical in ensuring that the right information flows to the right place at the right time.

Gathering the evidence

One of the biggest questions SIREN sought to answer was whether individuals who had previously been infected with COVID-19 enjoyed protection from the virus in future. Two groups of participants were studies – those with evidence of a previous COVID-19 infection and those without. When SIREN reported its first analysis, the study showed that 83% of people infected with COVID-19 had some protection against reinfection and this was part of the evidence demonstrating that individuals with a previous COVID-19 infection are likely to be protected against reinfection for several months.

And then vaccines came

As the rollout of vaccines began, the was study rapidly updated to include information about whether the participant had been vaccinated. By expanding the protocol of the study to include vaccine information, SIREN has been able to assess the effectiveness of vaccines. In February 2021, SIREN published findings that healthcare workers were 72% less likely to develop infection after one dose of the vaccine, rising to 86% after the second dose.

SIREN found that the vaccine’s protection starts after two weeks, and that this protection also helps to reduce the spread of infection. If an individual is not infected, they cannot spread the virus; the more individuals who cannot spread the virus, the greater protection for the whole population. By demonstrating an evidence basis for the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, the SIREN study has offered up a big answer to the question of whether the vaccination programme will help end lockdown restrictions: the answer is – in parallel with other measure including maintaining hand hygiene, using face coverings and observing social distancing – a cautious, careful, but optimistic ‘yes’.

Enrolling in the SIREN study

Since its inception, the SIREN study has answered and will continue to answer the most important questions about COVID-19 infection, reinfection and antibodies. The study continues to actively sign-up new participants through NHS trusts. However, recruitment ends on 31 March. So any health worker looking who would like to participate in the study should contact their local research team as soon as possible.

1 comment

Comment by Harry Sheils posted on

There have been some disgraceful reactions from politicians, who we rely upon for protection, which must have had a negative effect on outcomes!