The Health Profile for England report shows that although we are living longer than decades ago, we are not necessarily living healthier lives. This trend opens up discussion about the question and opportunities that an ageing society presents.

An ageing population leads to cost pressures if older people are more likely to develop chronic conditions with multiple morbidities, which are more costly to treat. But this is not necessarily a foregone conclusion.

In fact, the compression of morbidity hypothesis suggests that advancement in technology and prevention will postpone the onset of chronic illness, with morbidity becoming ‘compressed’ into shorter periods just before death.

Conversely the expansion of morbidity hypothesis suggests that while mortality decreases due to medical advances, morbidity increases because people no longer die from certain conditions, instead spending more time with disabilities or in an unfavourable state.

Morbidity is a multi-dimensional concept and the process of health changes that precede death can incorporate complex diseases, functional loss and frailty. There are a number of ways to measure morbidity and different studies reach different conclusions on whether we have compression or expansion of morbidity depending on the measure of morbidity used.

Trends in morbidity and mortality

As described in the Health Profile for England report, mortality rates have generally improved over time, both overall and for a range of causes, although there has been a slowdown in overall improvement since 2011. For example, death rates from heart disease and stroke have halved since 2001, for both males and females, and death rates for some major cancers (e.g. lung cancer in males and breast cancer in females) have also declined. On the other hand, deaths from dementia have increased in both males and females.

These trends partly reflect the fact that we now have better prevention and treatments for some diseases, and the majority of deaths now occur among those aged 75 and over, but also reflect an increased awareness and diagnosis of diseases such as dementia.

As a consequence of these changes, the Health Profile for England report shows that the average number of years lived in poor health increased slightly from 15.7 to 16.2 years and from 18.6 to 19.3 years for males and females respectively from 2009 to 2011 to 2014 to 2016. In addition, the proportion of life spent in poor health increased slightly. There are also substantial inequalities and the gap in healthy life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas of England was around 19 years for both males and females in 2014 to 2016.

This seems to suggest an expansion of morbidity in particular among the elderly when self-reported measures of health are used. However, there is no conclusive evidence on whether there is compression or expansion of morbidity as this depends on the health indicators used. The Centre for Longitudinal Studies at UCL is currently conducting a systematic review of the evidence which will shed some light on this issue.

Is ageing leading to an increase in health care costs?

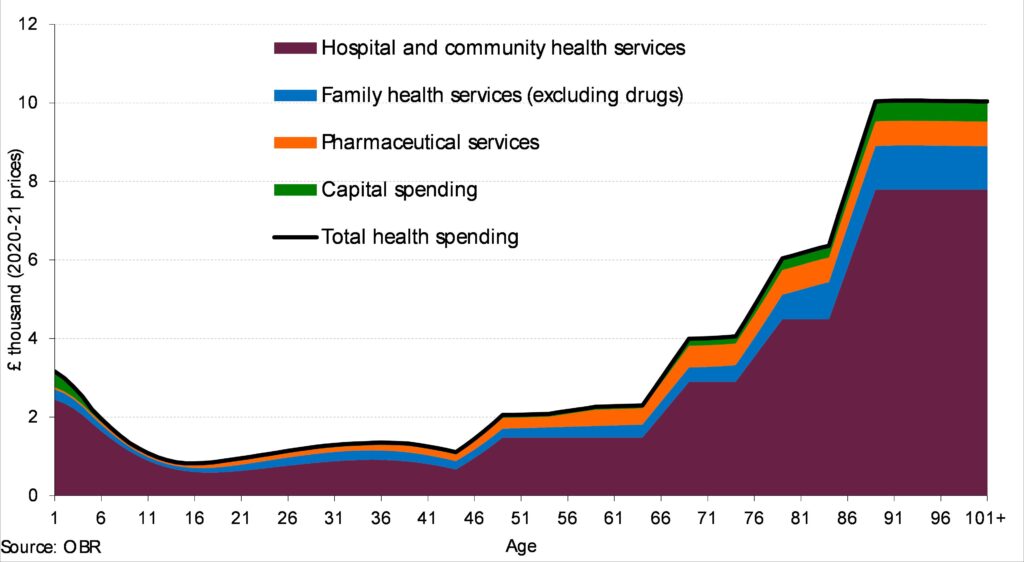

Age is a driver of health spending which is partly due to the fact that the prevalence of multi-morbidity also rises with age. As shown in the graph below from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBD),the cost of caring for older people - taking into account hospital and community health services, family health services and pharmaceutical services - increases with age.

Source: OBR, Health spending per person

However, several studies have confirmed that it is not age per se, but time-to-death, particularly the final year of life, that is a stronger driver of healthcare expenditures.

Healthcare costs in the last year of life also depend on age, but in this case there is an inverse relationship between age and the cost of end of life care. Costs are high for people dying at comparatively younger ages (<70 years), and appear to decrease with increasing age of death, mainly due to a decrease in hospital care.

This suggests that proximity to death is a more important determinant of health expenditure than ageing alone, and that living longer is not necessarily a burden on the health system.

The economic value of living longer and healthier is clearly a complex issue and is difficult to quantify. An ageing population may lead to increasing cost pressures through increases in health and social care costs as well as expenditure on pensions. However, this has to be balanced against added value to the economy due to increased revenues from direct and indirect taxation as well as volunteering and caring activities.

We want the data from the Health Profile for England and the narrative of the story it tells to be used by decision makers to play a role in creating policies. Download the graphs and infographics and use them to inform constructive conversations about the health of people both locally and nationally